I was pedaling my bike up a small hill on a narrow, beat-up asphalt road—this was LA, and I didn’t own a car. The sky was clear, cerulean blue, and the bright California sun shimmered through eucalyptus leaves, casting dappled light on me, the green hedges that lined the way, and the red-tiled roofs above them. The breeze carried scented swirls of salty, refreshing Pacific Ocean mist and the arid, musky smell of eucalyptus.

239 Palm in Red, 2014, oil on canvas, 18x24”.

At the top of the hill, the road opened up to a proper boulevard, Santa Monica's Ocean Avenue. And on the right, with a 101 address, was a magnificent white, modern cement-and-glass lobby, divided by the blues of the sky and the ocean. The building had a one-story profile, but it was, in fact, an apartment high-rise. Instead of rising from street level, it descended about ten stories, hugging the cliff face and stopping just above the Pacific Coast Highway that ran along the beach.

240 101 Ocean Avenue, 2009, pastel, 18x24”.

I was riding my bike from Nancy Frey’s compound at the bottom of the hill, where I was living, and heading to my art studio-gallery a mile away on Colorado Boulevard, the same street that runs into the Santa Monica Pier. Along the way, I passed a golden apartment building, and I always enjoyed seeing the palm tree’s shadow cast on the front of the building (Palm in Red). As I continued on, my thoughts turned to the lesson I was about to give to Chan Luu, the famous international designer who was studying with me privately.

Chan Luu

241 Chan Luu and me, c. 2009, Christmas day. Hill House, Pacific Palisades, California.

A few months before, Chan invited me to spend about ten days at her home in Kauai, where we painted intensely for about fourteen hours a day. Chan is the only person I know who can go toe to toe with me, maintaining artistic focus for long stretches. On our breaks, she effortlessly made excellent meals, keeping our creative energy at maximum flow.

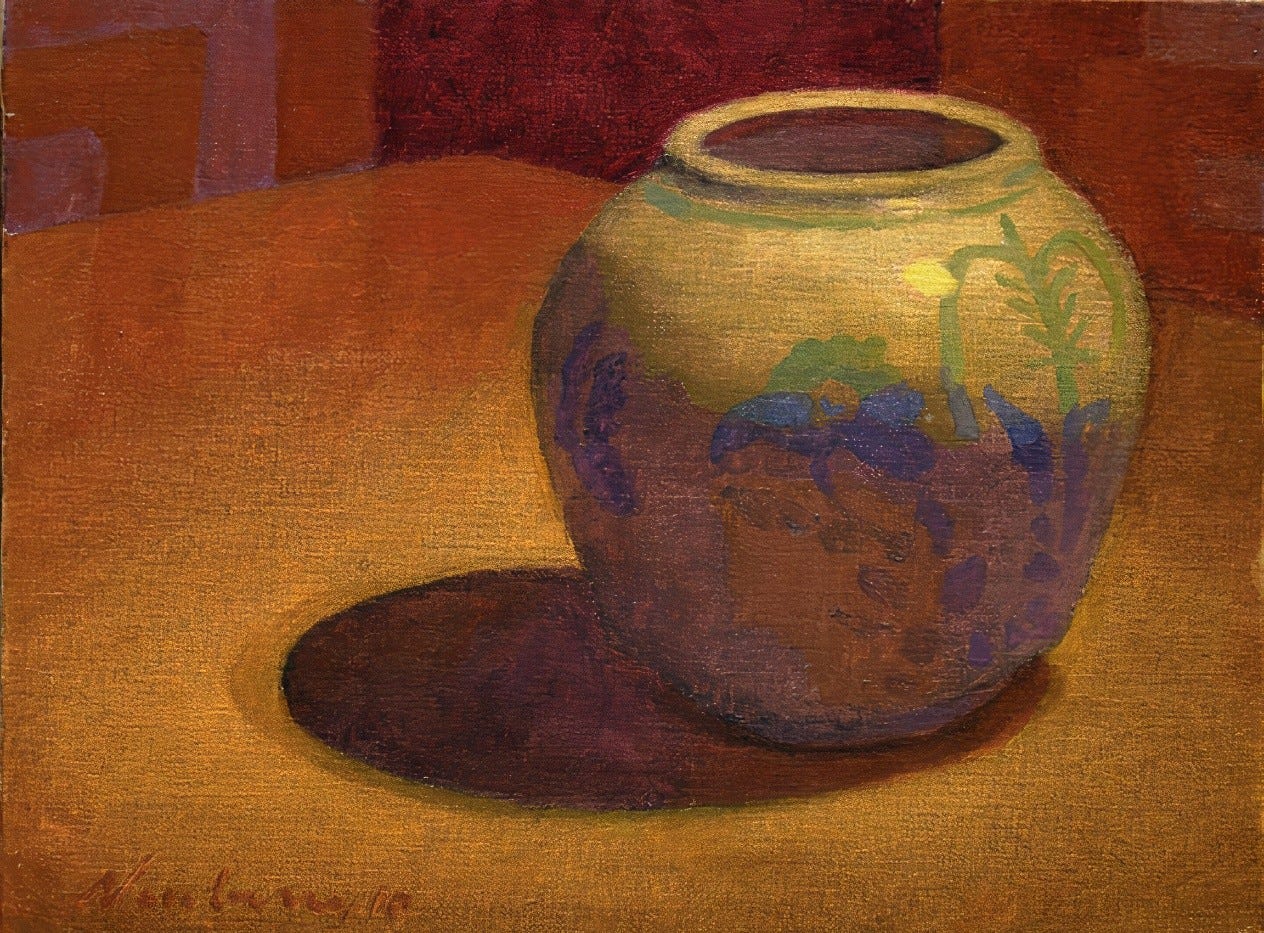

I vividly recall when she asked me to give a demonstration, painting an object from start to finish. (Painted Ceramic Vase, below). She sat close, intensely observing every mark I made, occasionally asking a simple question. It was an amazing feeling of visibility.

242 Painted Ceramic Vase, 2008, oil on panel, 9x12”. Kauai.

After I finished the demo, she began a still life painting of a sandstone orb she had brought from her business trips to India. Like a photographic memory, she could recall the techniques I used at every stage, and within a couple of hours painted a truly gorgeous piece, wonderfully in her own style, not mine.

243 Chan Luu, Sandstone Orb, 2008, oil on panel, 9x12”. Kauai.

244 Chan Luu, Flowers.

There’s a common misnomer that a teacher always learns from his students, which is rarely true. But in this case, Chan was on a quest to be able to quickly finish a painting from start to end. While I usually love to edit, for some time I’d been puzzled by the problem of how to quickly finish an Alla Prima (one sitting) painting. I knew how to do it in pastel drawing without any problems, but oil painting was a bit more problematic. So, with Chan’s nudging, I began experimenting with techniques in oil painting that would enable quick resolutions without that muddy, dull look that often happens with the wet-on-wet painting technique.

My Alla Prima Technique

245 Four shell paintings, alla prima, oil.

I can’t say I invented this technique, but I did come to it on my own, and it works very well. Looking at your scene, in this case my still life, look for one of the dark shadow colors, then tone the entire painting in that color. Next, use the end of the brush or a palette knife and sketch in the composition. Then mark the divide between areas in the light and in the shadow. After that, take sturdy paper towels and wipe away the paint in all the light areas, leaving the darks untouched. After that, in the shadow areas, paint what you see. A cool thing happens when you start to paint wet on the wet shadow color, it acts like a screen or veil, muting and creating mystery in all the shadows. Once that is done, paint the light as you see it. Since the surface was wiped clean, your highlights will be clean and unmuddied.

Creating a Series Intentionally

In the past, I created series of works unintentionally. I was simply out painting plein air landscapes on same-size panels, or drawing pastels on identical sheets of paper. Working outdoors, I might make three or four artworks in a single day. Naturally, they shared a similar subject, location, time in my development, and mood. But I wasn’t thinking in terms of a “series.” I was simply taking one painting at a time and resolving it in a way that felt right for that piece.

Chan introduced me to the idea of creating a series intentionally, using the same subject matter, the same size, and a consistent orientation. For example, three pastels could become one project, like Textile Bowls.

I don’t know a fine artist who hasn’t struggled to make ends meet, to inspire sales, or to evolve their career. These challenges are like working a second job as a salesman. But Chan pointed out that a series, say three works, naturally speaks to the viewer. It pulls them in, encouraging them to recognize the relationships among the pieces. Without a sales pitch or write-up, the series itself invites people to look deeply, to compare and contrast.

When I started showing a series, I began to see it: people became infatuated, absorbed in noticing patterns and variations. The works spoke to them in a way isolated pieces often didn’t.

For instance, when showing a 6x6” oil still life next to an 18x24” pastel landscape next to a life-size figurative oil painting, the viewer doesn't see a connection between those three artworks. The experience can freeze the mental and artistic experience. Consequently, the viewer has to recalibrate for each work, resulting in an exhausting and fragmented experience.

The opposite effect happens when viewing a series. It invites and creates a feeling of flow and connection.

246 Textile Bowls.

247 Flowers Up Close.

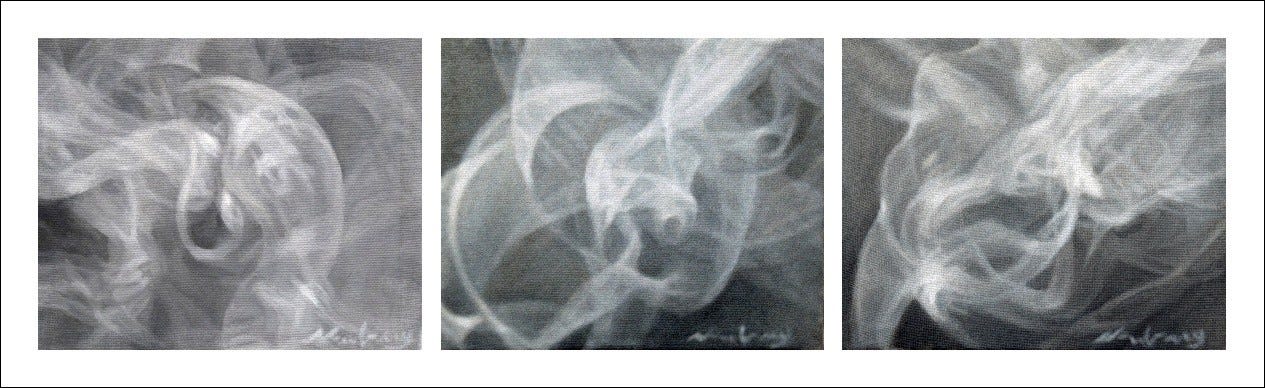

248 Smokes Series.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of Navigating LA.

Author’s Note: It’s strange writing a memoir especially when getting closer to the present time. I still have about a decade of artwork to cover, but I noticed that I am slowing down on writing! I don’t know if it is because getting near the end of memoir suggests an end of life, god forbid! Or, that I feel like I still have a couple of more decades of new art to make. It is a fascinating paradox.

The baskets are luminescent. Your talent is never ending. Always surprises. Smooch! I still cannot get the Puccini out of my head…the pose was so personal, like I was in a dialogue with him. On dialogues: the Nijinsky family asked me to check on Vaslav in the Montmartre Cemetery to see how he’s holding up. I did last Wednesday. I wish I could put a photo of the two of us having a conversation - as we both dislike the pose/role the sculptor has but him in-Petruschka,- a puppet for all eternity. Damming. The family will have a meeting🤷🏼♀️We are thinking about me creating Afternoon of a Fawn, iconic Nijinsky via Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe Paris premier…. And the Rites of Spring, heart stopping.

Did you know Stravinsky was becoming a lawyer until D plucked him up? What are the odds.

Beautiful story you have shared M

xx

em

Such an inspiration to read this - an inspiration to write and to keep learning and living. ❤️