A bit anxious and tremendously excited, I was now free to devote everything I had to creating my next major painting. It might seem competitive that I wanted to compare my development with my art heroes. But it wasn’t competitive; rather, it was honoring my feeling for art. When I saw a masterpiece by Rembrandt, or by another favorite artist, the feeling of love, admiration, and care was earthshaking to me. I wanted to be able to feel those same things for and from my artworks. I surmised that if I could be that passionate about their works, I should be able to unlock it within myself. I would hate it if I did indeed have the potential but then did not exploit every kernel of my possibilities—it would feel like a lost opportunity and perhaps a road to an unfulfilled life.

A year earlier (March 28, 1982), I was listening to WQXR presenting a live concert at the Met, Metropolitan Opera House with Marilyn Horne and Leontyne Price, conducted by James Levine. I didn’t expect anything, but it was kind of cool knowing that this concert was going on live in Manhattan, just a ferry ride away.

I had transitioned to listening to classical music from pop because of its bigger forms and longer duration. I knew opera mirrored classical music, but the sound of opera singers didn’t appeal to me. Yet, Leontyne Price woke me up, holding a crazy long, intense note at the end of a Verdi piece. It was like a soulful cry to be loved, yet it was also beautiful and strangely triumphant. It was similar to what I felt for Rembrandt. Instead of swirling vibrations of paint recreating a sensitive woman, it was vibrations of human sound that pierced my heart and soul.[1]

And then I had my first introduction to Puccini. Price sang “Chi Il Bel Songo Di Doretta” from Puccini’s La Rondine. That moment was to start my lifelong love affair with Puccini and Price. Whatever magic “it” was I wanted to be able to translate that visually.

Later I heard an interview with Price and she was asked, "What advice would you give to a young singer?" And her reply was, "To love your voice." Though that can sound like a cliché, aesthetically it defines the "it" feeling in creating art. And for me it means loving the feeling of every painted brushstroke, and more.

"Loving your voice" is a call to discover and master all the tools that enable your expression to reach its peak. In tennis, it is called the "sweet spot." The tennis great Jimmy Connors commented that if he didn’t feel he was playing well, then he would concentrate on the sound of his racket striking the ball. When that sound became the right frequency, he knew his game was back in top form.

Additionally, there is its metaphor: that your voice is your stance towards existence. When added to technique it creates a techno-spiritual integration. For instance, harmony is both a technique and a spiritual state. And you can break it down to things like calmness and horizontals; dynamism and diagonals; stoicism and monoliths; and etc. But the biggy is loving the ends and the means. Hence, “Love your voice.”

Leontyne was also in the back of my mind whenever I felt that my art life was tough. I would take a second to think about Price as a black woman from Laurel, Mississippi, in the 1950s rising to the top of the operatic world. That immediately put my issues into perspective, and I would laugh at myself.

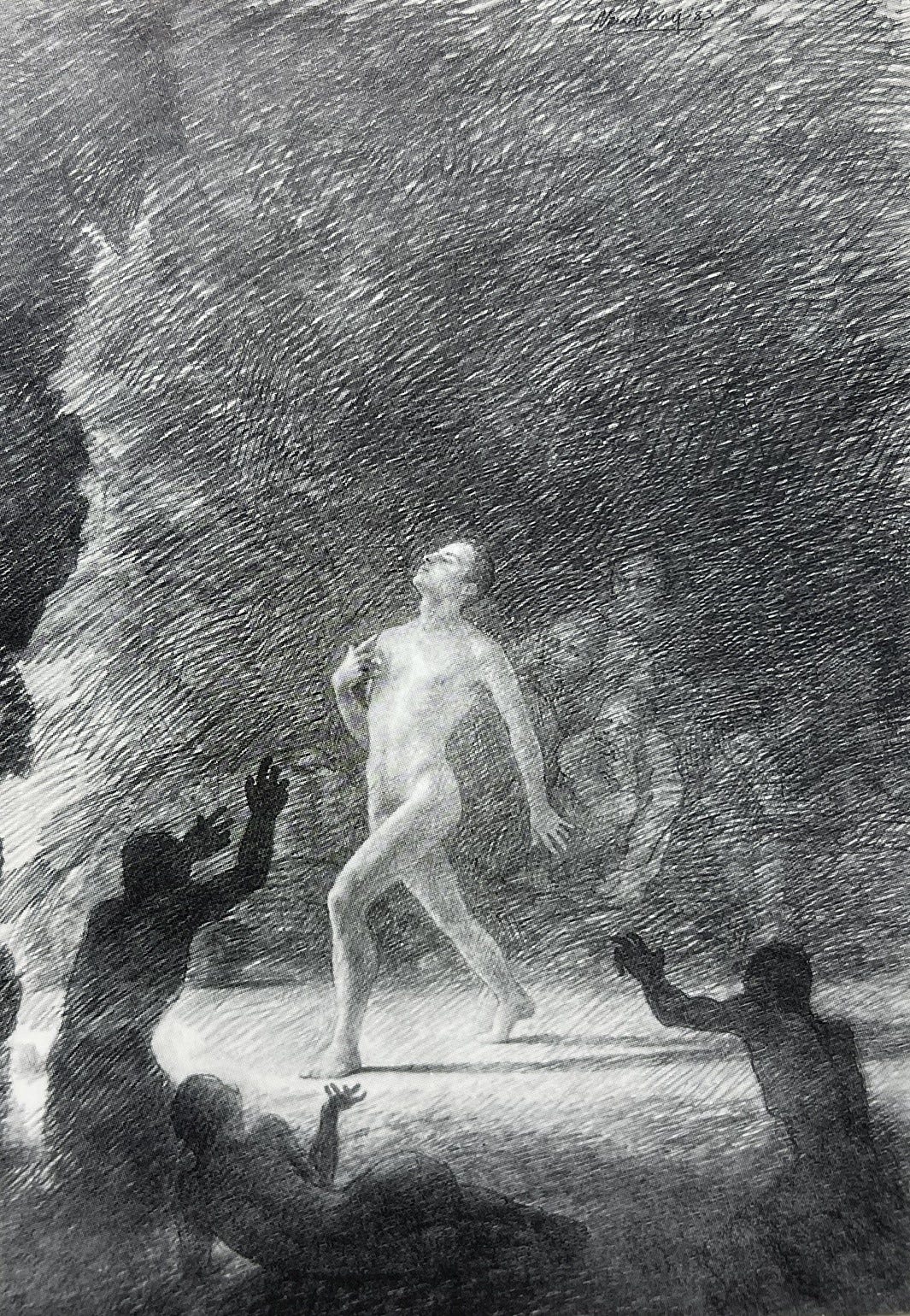

49 Castoff, 1983, graphite on Rives BFK, 24x16”.

Kant

Coinciding with my newfound love of Price was an introduction to Immanuel Kant’s aesthetic treatise, Critique of Judgment. I had suspected that he influenced postmodern art, and what better way to find out than to go to the source? I must have read it about 200 times; it is foundational in its way. When I would come across a postmodern puzzle, like the massive temporal project of Christo’s Umbrellas—2,000 huge industrial umbrellas split between locations in Japan and California—I would recall something Kant would say. Such as his discussion on the mathematical enormity of things which go on infinitely in number, so vast that our brains can’t comprehend it, and hence for him, the sublime, i.e., the absolutely great.[2]

One of his criteria for the sublime is we can’t fathom it, and the contemplation of that "does violence to our imagination." Imagine reserving the evaluation of great and sublime to things we don’t understand or comprehend? Whether knowingly or not, Christo’s project of thousands of umbrellas receding and disappearing in the hills, looking like they go on forever, is a perfect application of Kant's mathematical sublime.

Kant used a very clever PsyOp, psychological manipulation, when he contrasted beauty in art to his nihilistic sublime. In every instance, he claimed the superiority of the sublime because of its formlessness and incomprehensibility, while beauty in art was merely a craft: a comprehensible thematic thing that involved the senses. Ultimately Kant wanted to grab the concept of the sublime in art, redefine it as mystical nihilism, setting himself up as the high priest of the sublime, and then reduce the best of art to a matter of decorative taste. Meanwhile, the original concept of the sublime, noble and uplifting, disappeared from the art lexicon. This antagonism of art’s noble purpose, became the aesthetic foundation postmodernism’s anti-art platform.

I brought up Kant because when you study things that challenge your worldview, then arrive at a thorough understanding of them, if they are antithetical to your worldview, then you can walk away and toss them off as bullshit. Instead of experiencing angst, this new understanding greenlights you for where you want to go.

Castoff

Two drawings included in the 1983 New York exhibition are Castoff and Pursuit. They were suggesting the intense themes I was growing into. Castoff depicts a man stepping into the light out of dim cave’s shadows and away from apathetic inhabitants. You can see the influence of both opera and my rejection of Kant’s aesthetics. I didn’t know at the time that Castoff would be prophetic.

Of the two, I decided to turn Pursuit into a fully developed large painting.

Pursuit

My Staten Island art studio was a one-bedroom apartment on the ground floor. It had high ceilings and tall windows. The main room had one naked 110-watt light bulb in the center of the ceiling. Reflecting back on that period, I can’t believe that was enough light to paint by. But, it did create a very nice dramatic light when I worked with models.

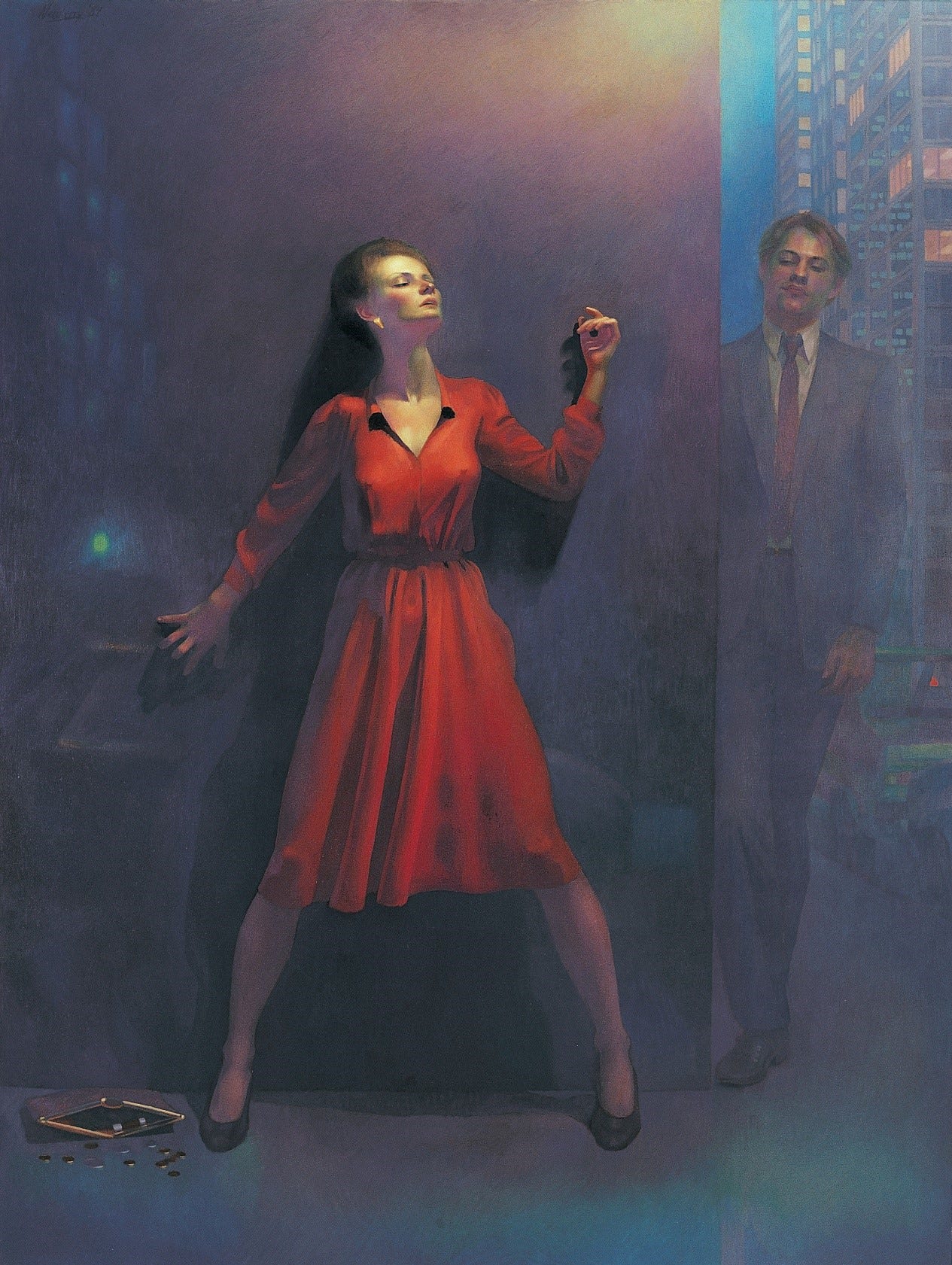

The original concept for Pursuit was about climbing Mount Everest, man conquering majestic nature. But I had this overriding feeling that the greatest feeling and challenge for humanity is burning romantic love. So I came down to earth and set up a scenario on a Manhattan sidewalk where two strangers are irresistibly attracted to each other, but in a challenging context.

A few times in my life, I have felt “love at first sight” so powerful that I could barely breathe and my heart was jumping out of my chest. Following up on that feeling led to incredible and fulfilling relationships. So the concept of Pursuit was something I could relate to and felt authentically possible in life.

Jennifer Trainer and I posed for Pursuit. I wanted to use the Ancient Greek and Italian Renaissance technique of starting with a nude and then adding the clothes, creating a wet-cloth look. I looked for the nude self-portrait drawing, but I couldn’t find it in my files.

50 Pursuit, 1983, graphite on Rives BFK, 24x16”.

The process involved drawing countless studies in graphite and pastel of both the figures and the setting. It was kind of amusing to draw Jennifer naked, wearing high-heeled shoes, but it would make a big difference in the final painting to have done that to give it a natural feeling of her dressed up. The one light bulb in my studio ceiling created a really nice light fall on our bodies, a nice balance of highlights and shadows, and the cast shadow on the wall, with sharper and darker tones higher up, closer to the light source, then fading as it dropped away.

51 Study for Pursuit, 1984, graphite on Rives BFK, 18x12”.

After drawing the nude, I did a pencil and pastel study of her wearing a silk red dress. I followed the same process for drawing myself, except using a mirror. For the color study of my face, notice the range of colors: yellows, pinks, oranges, some greens, purples, and pinks. In real life, I can see a whole kaleidoscope of color nuances, and the pastel helped me transfer those to the painting.

With the figurative references done, I then went several times into Manhattan at night, specifically into the Wall Street area, and drew pastel nocturnes of the granite sides of buildings, the sidewalks, cars, and some of the buildings in the background. The place was deserted, except for a couple of security guards. I would sit on the sidewalk with my back to a wall, surrounded by my pastels, using a street lamp for my lighting. I was capturing all the subtle reflections that I could see in the wall. I remember a security guard looking really puzzled. I could almost hear him thinking, “Geez, crazy artist.”

Once I had all my preliminary studies ready, I stretched the canvas, primed it, and began sketching in the composition. I began integrating all the information that I had gathered and from the moment I started working on the canvas, it became a six-month project, dedicating 16 hours every day to it. It was my sole objective, which I could afford since I had funds from the previous show.

I took three to four months to paint a brown underpainting using raw umber. Then I began the difficult stage of layering color on top of the brown underpainting. The underpainting established the tonal values from light to dark in the shadows and nuances. Then, when adding color, I aimed to maintain these tonal values while introducing different hues. Achieving the right color and tone layered on the painting felt amazing, like fitting a piece of a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

Two symbolic elements of the painting include the notable open purse on the floor with some coins spilled out, and the green light reflected on the wall. For me, the image of the dropped purse signifies that the robbery was the furthest thing from her mind. With the purse opening facing us, it suggests a glimpse into her privacy and her openness to the encounter. The green light symbolizes that all systems are go. Though I also included a tiny red light off to the right, aesthetically balancing her red dress.

Near the end of finishing the painting, I had worked until two o’clock in the morning, went to bed, and woke up totally refreshed at 5:00 AM. I decided to have breakfast in Manhattan. While I was on the ferry, I was wondering if I was maybe going crazy.

Painting for 16 hours a day is so intense; all you can think about is all those creative elements going through your brain. I was questioning how healthy it was to remove myself from the world. As I contemplated these thoughts, the sun was rising and beginning to cast its light on the Statue of Liberty.

I was observing how the colors and light moved across the landscape of the sky, noticing the subtle changes in both hue and tone, much like in my painting. As the golden light turned the highlights on the Statue of Liberty to a warm greenish tone, I realized that everything the painting was based on stemmed from my connection to reality— from the dozens of studies I did observing figures, clothes, colors, atmosphere, and skin tone changes.

52 Self-Portrait (1984), pastel, 24x18”.

Without any filter, I had fine-tuned my perception of all the visual elements. Instead of divorcing me from reality, recreating my direct perceptions in the painting became an important tether to reality and, consequently, to my mental health. Once I realized the connection of my art to perception, I could feel secure in giving painting 100% of my focus—instead of losing my mind, it was intensely fortifying it.

One of the goals I planned for in this painting was to merge fresh color and realism. With the French Impressionists, you will notice that their technique isn't very refined or realistic in terms of detail because of the abrupt color changes. In classical realism, a brown technique is easier to refine details. My goal was to achieve both. Notice the large range of color changes on her face with yellow, scarlet, and some greenish ocher. While the shadow on her face has a magenta-purple tone, which, against the dark purple wall, creates a kind of pale-skinned luminosity, giving her face and neck a porcelain-like quality—a colorful paradox.

In a quirky way, my interest in integrating surprising colors with realism came about from listening to Puccini’s operas. While I'm no expert in music, having never played an instrument or sung, the thousands of hours I spent listening to his work led me to marvel at his orchestration. Puccini used very strange combinations of sounds that made me wonder, "What are the instruments making that magnificent sound?" Yet, despite the unexpectedness, all the sounds flowed in harmony, never losing sight of the big picture of the music. His ability to combine unexpected instruments, beautiful melodies, and tremendous passion were the goals I wanted to achieve in my painting.

When I finished the painting, I was over the moon in the most profound way I’d ever experienced. I had achieved everything I set out to do, and the results pleased me more than I could have hoped. Even now, some 40 years later, when I see the painting, I feel the same youthful enthusiasm and feedback loop that I felt when finishing it.

53 Pursuit, 1984, oil on linen, 80x60”.

Rejection

Now that the painting was done, I felt it was going to launch my career. I believed that anyone who knew anything about art would recognize the effort, skill, and passion that went into it. But I did not have much time, as I was running out of money. I could live for another two months, but then I would be broke.

In the mail, I received an invitation to make an appointment to meet with an art advisor in Manhattan. She had seen my invitation to the 1983 New York show and was interested in representing me. This was in August, and the weather was hot, so I was dressed casually in tennis shoes, Adidas running shorts, and a fitted T-shirt. When I arrived at her small office, I was surprised it wasn't a gallery. Likewise, she looked surprised when she saw me.

And in the kind of New York brisk way, she said, "Look at you. How can you be the artist?" And I was like, "What?" And then carefully I replied, "You were impressed by the painting, and its quality and size. That should stand as a testament to all the effort, time, and passion I put into it." Apparently that didn’t convince her. And my physical presence didn’t fit with her preconceived idea of what an artist should look like. So our appointment fell flat. And I thought it was her loss. Of course, in hindsight, maybe going in my running outfit wasn’t the best idea?

One day, I rented a U-Haul truck to take Pursuit into Manhattan for an appointment I had with a mid-level art dealer. When I came in with the painting, the expression on her face was one of surprise and a little bit of fear, which I couldn’t comprehend. I placed the painting against the wall, and we talked for a few minutes. In New York, not only do they sell paintings per square inch, but time is also a commodity. She then turned her attention to the painting. It's a big painting, 80 by 60 inches. She walked up within a couple of inches from it, and for the next 10 minutes, she looked at the painting from two or three inches away.

Now, the quality of a painting is that it holds its integrity over huge distances of space. So, to get the full impact of a painting, it’s really important to see it from a great distance. And then, if the details work well up close, it’s a really impressive feat. So here, she's looking at the painting with her nose almost on the painting.

And I’m looking at her thinking, what the fuck is she doing? And in the course of that 10 minutes, I could tell that she was extraordinarily uncomfortable and not seeing anything. She didn’t know what she was looking at, and I could sense that she knew that I knew. She was frozen with her face in the painting and finally said, “no, this isn’t right for our gallery."

I then asked, "Do you know what gallery might be a good fit?" And generously, she suggested a gallery in Soho. She actually called the guy up and said, "There’s an artist here with a painting you might be interested in." So I took the painting back to the U-Haul and drove it to Soho, and met with the dealer there. We had a short meeting. He seemed kind, looked at the painting, and then unbelievably said, “New York isn’t ready for this kind of artwork.”

I was shocked into silence, thinking that New York, on the cutting edge of everything happening in the world, couldn't possibly be a conservative backwater stuck in traditional ways. How could it not be ready for what's new? I didn’t bother replying and took Pursuit home.

Afterward, I tried a different approach. American Artist Magazine featured a series on new and upcoming artists, often showcasing figurative work. I sent a press package to them and received notification from an editor who loved the painting. I felt excited, thinking this might be the opening door. A few weeks later, the editor called me, expressing deep apologies, as the chief editor decided against including me in their feature as an up-and-coming artist. When I asked for the reasoning behind this decision, she revealed that her boss had cited my gender and location as reasons for the rejection.

With my funds quickly drying up and zero prospects in sight, I made the decision to leave New York and return home to La Jolla. My grandmother and my dad lived there, so I would have a place to crash while figuring out my next moves.

As I packed up my stuff, I had to take the canvases off all the stretcher bars and roll them up, putting them in a PVC plumbing pipe. Then, I rented a large sedan and began my drive to California from Staten Island. I don’t remember feeling disappointment or doubt due to the rejections from the New York scene. The only emotion I recall regarding those setbacks was numbness. Internally, though, I felt like I had finally become the artist I aspired to be. Like Castoff, I was stepping out of the shadowy New York and heading for the light of California.

[1] A few years later, around 4 am, standing in the waiting line for standing room only tickets for Price’s farewell performance in Aida at the Met, it seemed that all the other opera fans also had an unexpected eureka moment of intense love like I had.

[2] For a more detailed exploration of Immanuel Kant's influence on postmodern art and a comprehensive analysis of his aesthetic treatise, see Michael Newberry, Evolution Through Art (Self-published, 2022), Part Two, Chapter 5: Kant.

Thanks for sharing your process, it completely changes your perspective on a work when you can see all the developmental stages. It is a raw and emotional painting. In regards to your 'rejection', that is everything that is wrong with the art business - the gatekeepers who make or break an artist's career in a moment based on their gut intuition and a deep desire to preserve their own reputation in a market based solely on trends.

Now, in the digital age, we have a new set of gatekeepers for artists that are forced into the world of 'content creation' and attention based audiences. Algorithms that are based on the whims of a massive, random selection of people looking for a quick and shallow dopamine hit. Hard to say which gatekeepers are worse. Neither one is a win for the artist.

Utilizing every aspect of what makes your life meaningful Michael to paint, draw and awaken my wonder and awe, at what a human can place on a canvas, excites wonder and awe. Beauti is seen by all as LOVE, dear Michael, and it awakens a deep spiritual and soulful meaning of being that connects us all. Right now we need what connects us all. Thank you Michael for your gift to me this night. Sharon