Memoir: Chapter 4, Commuting Between The Hague and New York

An Art Memoir: Depth, Light, and Love

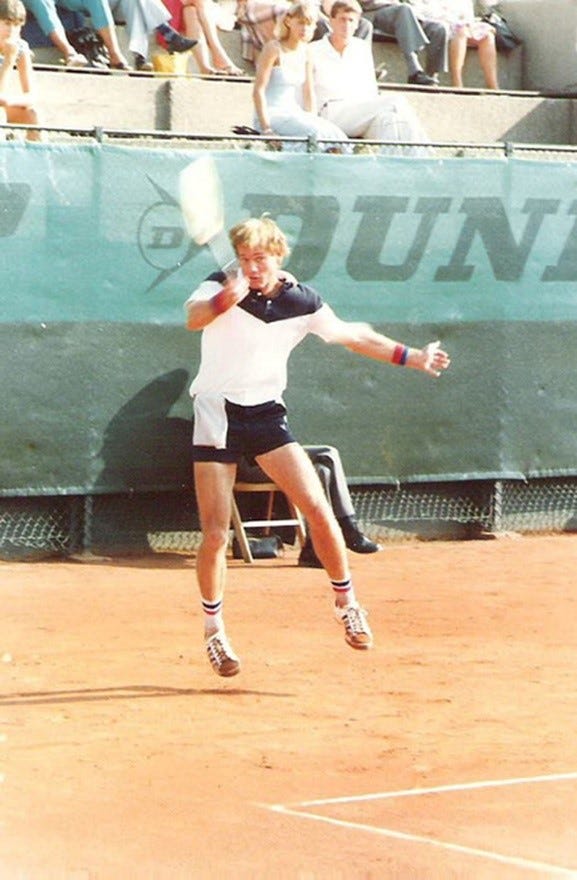

In 1977, my sister Janet reached the semifinals of the French Grand Slam at Roland Garros. I drove to Paris from The Hague to see her play in the finals if she won the semis. My car was a tiny orange Simca 1000, kind of like a go-kart. Instead of the finals, we drove back to Holland via Mont Saint-Michel and had lunch there. That was the first time I had mussels, yum.

After we arrived in Holland, Janny gave me a thick novel, Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand. A year before, Janet had already successfully suggested I read Mary Renault’s historical fiction covering the life of Alexander the Great. I found Atlas to be inspiring and gave me a “pat on the back” for my decision to pursue art.

25 Me in 1977 in The Hague, Holland.

Now that I was done with my full-time art studies, I wanted to give New York a test run as an artist. That summer, I found a one-bedroom in the East Village. A guy in his 30s, apparently part of a government program to revitalize the bad areas of the city, was the manager/owner of the previously derelict 3-story building. Momentarily without hot water due to its minor improvements, he leased all 15 apartments at once, and then left the US for the Caribbean with the first, last, and security. Despite the chaos, I painted 24/7, since we had electricity, and we could boil hot water to take lukewarm baths.

In the fall, we organized a tenants’ association so that we could manage the building. We still didn’t have hot water or steam heat, and winter was coming. The city couldn’t or wouldn’t help us, so I called an oil company, figuring they would make money if our building’s boiler worked. They fixed it all up the next day.

A side story: in trying to get help for our building’s predicament, I had met with my first Manhattan socialist. There was an organization that helped with tenants’ rights; it was a hole in the wall, and I spoke with an advisor, a woman with an ash-gray complexion. She wanted me to take my savings, a year of living expenses dedicated to full-time painting, and donate it to the building’s fund. Her advice would have killed the start of my art career. Obviously, taking her advice was a no-go.

I lived ascetically; there was a table and two chairs in the kitchen, a roll-up foam mattress, and a radio/cassette tape player. That was it for furniture. My mom visited once, and she was horrified.

I got bored listening to the pop radio stations and started listening to WQXR, New York’s classical radio station. I was kind of indifferent, but at least it didn’t endlessly repeat; a piece could last a half hour or more. Slowly, I would hear a piece I liked and go buy a recording of it. Bach’s Air on G String was the first catalyst. I also discovered Andrei Gavrilov, the great pianist, and we would become friends 40 years later. My paintings were becoming more time-intensive and taking much longer to finish, and the classical music psychologically prepared me for the long haul.

The Self-Portrait, the Studio Interior, and the painting of Dagny (heroine from Atlas Shrugged) were all set up in my East Village apartment. For the Dagny painting, I took a scene where she opened a cheap office in the seedy side of town, conveniently mirroring my place.

26 Self-Portrait in the East Village, 1979, oil on linen, 50x20”.

27 East Village Interior, 1979, oil on linen, 60x40.

I really like my interior, a large painting 60x40’. It has a very difficult doorway through a window, to another window pattern. And the studio’s walls are covered in my life drawing sketches and another painting. The technique I was exploring was oil glazing, kind of like watercolor but with toxic oil painting medium made up of linseed oil, Damar varnish, and turpentine. I love to paint with it, but it will kill you in closed spaces working day in day out. I think the composition rocks, and the light works. I wouldn’t change a thing.

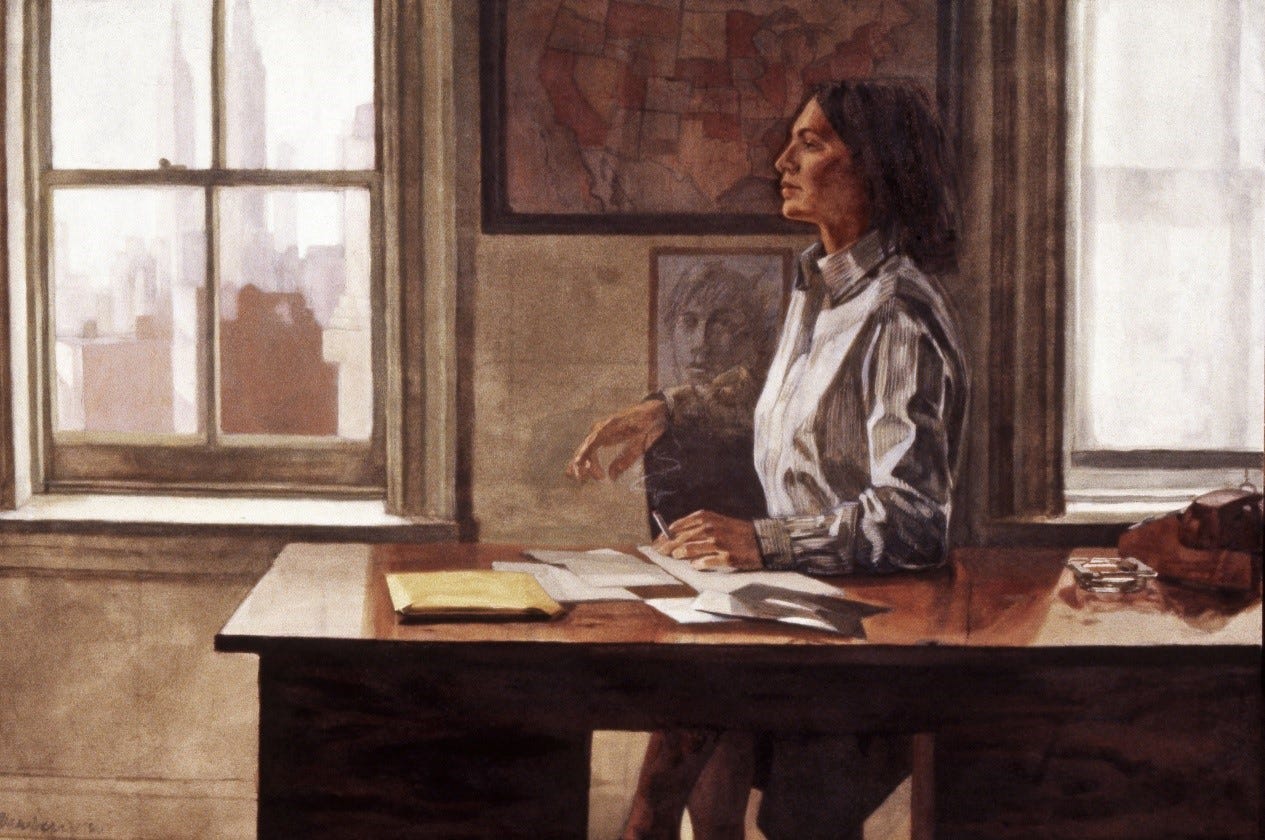

28 Dagny, 1979, oil on linen, 42x50”.

An aesthetic difference between the Interior and Dagny is integration. While I could just paint what I saw in the Interior, Dagny had to be constructed by the integration of different elements: the cityscape, the map on the wall, and the model, Jennifer Trainer, who lived on the floor below me. The aim in Dagny was to stylize a scene mixing reality with imagination yet make it look as natural as possible. One problem I never solved was that her legs don’t line up with her upper body; once I saw that, I had to destroy the painting. I did cut out her face and repainted it later. Today, I would have just repainted her lower part, but I didn’t have that editing understanding then.

Visiting New York Galleries

After finishing a few paintings, I had slides made, which were required by galleries if they were to review your works. One meeting I had was with Allan Frumkin, a figurative art dealer representing notable but, dull-as-cardboard artists Jack Beal and Philip Pearlstein. I recall that one of Beal’s paintings sold to a government agency for $50,000-75,000. Frumkin had an annoyed expression, almost angry, when he saw my slides, and dismissed my work as too lyrical. It was one of many puzzling rejections I would face for several years.

I was also puzzled by the ridiculous shows at the Mary Boone and Barbara Gladstone Galleries. One show at Gladstone was a massive pile of a hoarder’s studio crap, an 8’ heap filling the room with just enough space to walk around it. I was only 21 or 22 at the time, but I knew the “art” was bullshit.

My opinion was based on having taken and aced two years of postmodern installation art classes and contemporary art history classes. This firsthand experience gave me insight into the practice, only to find it was a modern construct built on nothing. It was literally an anti-art process, and it felt like it.

What I couldn’t figure out was why it was being shown. Who would buy it? Surely no one would put it in their homes? And it was presented without irony in an extraordinarily tasteful, well-designed, immaculate gallery, with equally styled assistants. No amount of thought could reconcile the contradiction.

I would see this same format for decades, even to present times: fabulous spaces, world-class presentations, promoting nihilism. i.e., literally piles of garbage.

After visiting contemporary galleries, I would be so depressed that I could not paint for days. Instead, I would devour books. Like everything by Renault, Rand (who was still alive and living in New York), Hugo, and Dumas. I read non-fiction such as Hamilton’s The Greek Way, Cottrell’s The Bull of Minos about the archaeological digs by Evans and Schliemann, and I even read Von Mises’s Human Action.

At this time, WQXR radio had an opinion segment which also invited a one-minute rebuttal. One commenter was so socialist, reminding me of the horrible rental advisor, I notified the station that I wanted one minute of airtime, which they gave to me! I talked on air about Von Mises—it was the one and only time I publicly talked about something that was not about art.

29 Woman in Blue, 1980, oil on linen, 50x32”.

Woman in Blue, Portrait of Jette van der Meij

The model for the realistic, life-size Women in Blue was Jette van der Meij; she had posed earlier for the 1977 painting Jetta. The painting combines the lessons that I learned from Rembrandt and Vermeer. I snuck in a painting tribute to Vermeer by including his book on the table. The concept for the painting was that she had a wonderful day out, walking in fields on a summer’s day, and she came in feeling refreshed and beautiful.

30 Jette van der Meij, photo by Otto van den Toorn, 2016.

This photo of Jette, several decades later, shows an expression and position of the face almost identical to my painting. Her expression also conveys intelligence, warmth, and a joyful confidence. At the time of painting Jette, it was so damn inspiring that she was studying music and theater, and doing performances of jazz. She would go on to star in a Dutch sitcom, Good Times, Bad Times. It’s deeply fulfilling to pursue art with friends who join you in understanding what it means to be an artist.

Late one night, midway through painting Woman in Blue, a windy hailstorm was endlessly ongoing. The damp and cold air, with hail beating against the window like drums, heightened an already frustrating moment I was having. I had been struggling for weeks with a technical problem in the painting, and in that moment, at two o'clock in the morning, I questioned what I was doing. Was it worth the struggle to be an artist? I could have been touring the French Riviera, playing tennis, but instead, I was experiencing full-blown misery. I pushed the thought aside and went back to painting. Within an hour, I had solved the painting problem, and all the questioning of what I was doing there completely melted away. I then experienced the ecstasy of artistic flow, and like magic, I was transported to a higher plane that made all the sacrifices worthwhile.

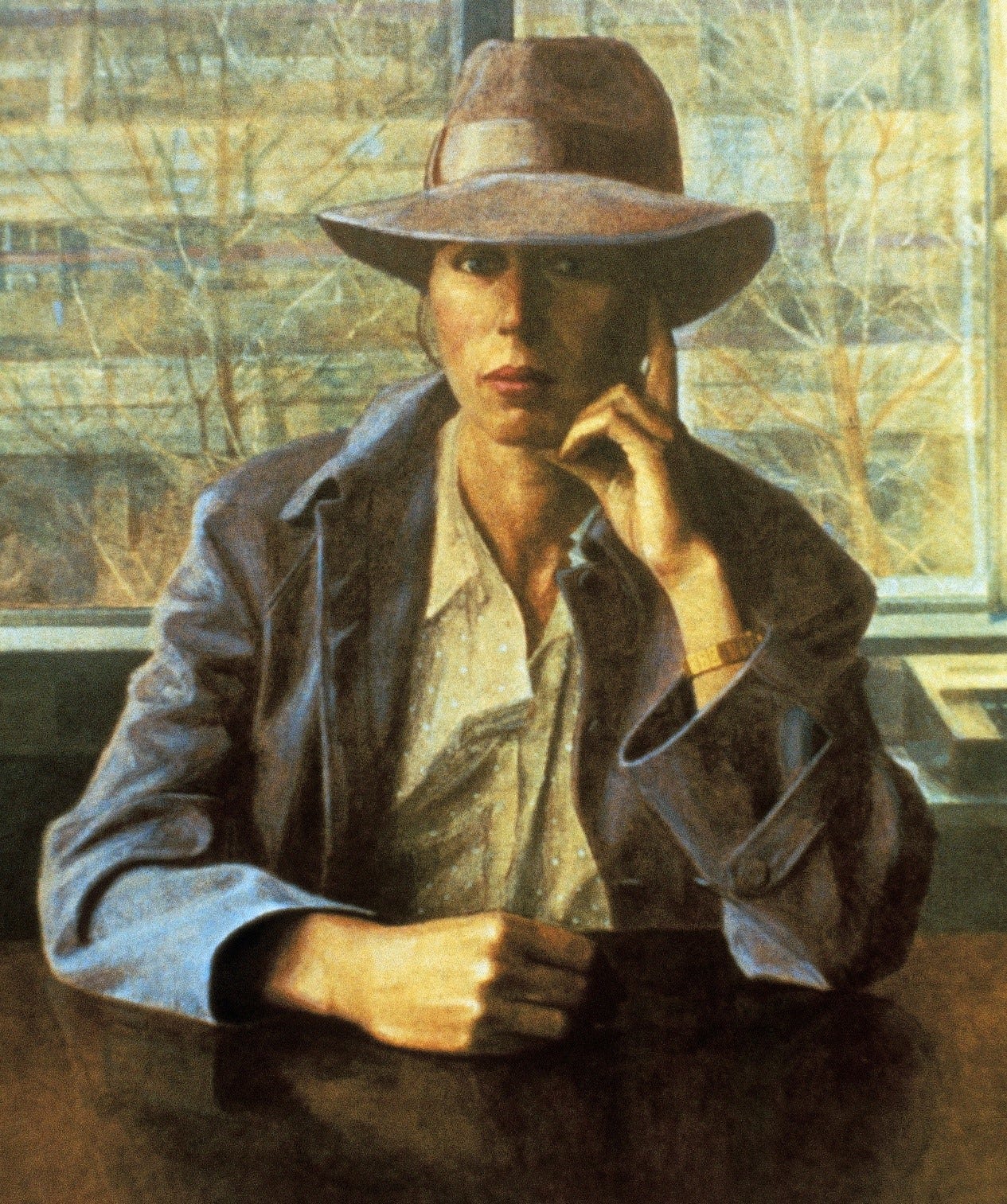

Woman Wearing a Hat, Portrait of Lynia Zaaijer

Some people just pop off the screen of life, and Lynia was one of them. She was a member of the Metselaars Tennis Club, and her house was adjacent to the courts. We were kindred spirits, although she was incredibly humble, while I, not so much. She was the owner of a fashion boutique and often did her shopping in Paris, staying up-to-date on the latest fashion trends in Europe. But beyond her accomplishments, Lynia was one of the kindest persons I’ve ever met. Her eyes and smile lit up any room she entered, and her energy never failed to reach me. It was such an honor for her to be my muse on several projects.

The idea behind Women Wearing a Hat was to portray a woman entrepreneur independently carving her own way through creative work. In this painting, I explored a classical technique I had read about, of using a brown and black underpainting, known as grisaille. The shadows and the tabletop are the original underpainting without overpainted touchups. Once the underpainting was completed, color was then layered on top. The entire work was done using oil glazes, which involve very thin and liquid applications of paint. The thinness of the paint created translucency, resulting in delicate vibrations throughout the canvas.

31 Woman Wearing a Hat, 1981, oil on linen, 38x30”.

32 A Writer and an Artist, 1982, oil on linen, 62x62”.

A Writer and an Artist, A Double Portrait

A Writer and an Artist is my tribute to the painter Vermeer, depicting a Dutch interior with people lit from the side window. Lynia and Rob posed for this in Holland. Vermeer’s paintings are all rather small, like 18x12 inches, but I preferred paintings of people to be close to life-size, as in this painting. I think it’s my first painting dealing with two people as the subject matter—a difficult technical problem because they have to fit into their relative space and look natural. If you look carefully at their positioning, Rob sits naturally back in space behind the corner of the table, while Lynia occupies the foreground space, creating an interaction of spatial optics. On the wall behind them, I included painted tributes of a portrait of Ayn Rand and a copy of Las Meninas by Velasquez.

The idea for the painting was inspired by my friendship with Jennifer Trainer, a New York writer who was my neighbor when I first lived in New York. She would temp as a secretary, and in her free time, she wrote fiction and nonfiction. One of her well-known books was a compilation she edited called Nuclear Power: Both Sides, co-authored by Michio Kaku, currently a popular physicist known for his book The God Equation. Their book had about 20 adversarial contributors, and they were all happy with her editing, which was an extraordinary achievement for a young woman (23 years old). Her workroom wall was taped with all kinds of notes, and we would have discussions about philosophy, art, and literature. I began the project in Holland, and Lynia and Rob gladly posed. I couldn't have asked for more perfect and inspiring subjects.

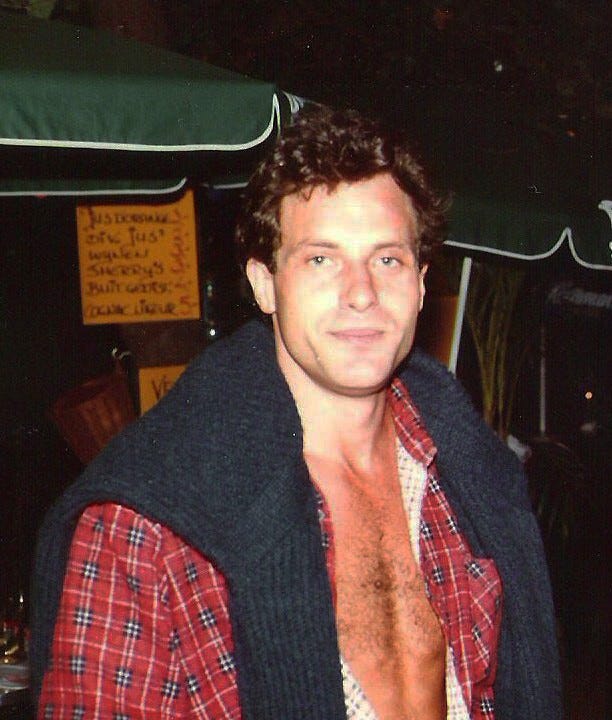

33 Robert Mechielsen, 1982.

Robert Mechielsen has been a lifelong friend and the most creatively passionate person I've ever met, mixed with a very generous and warm heart. He had a funny quirk: he couldn't comprehend dark humor, so cynicism or satire completely went over his head. When someone, or even myself, told a dark joke, he would simply look puzzled. It was so refreshing to have a friend who didn't feel the need to cloak pain or hurt with irony.

Rob posed at the Free Academy and for several of my paintings, and he was also studying the figure and sculpture there. He also had expertise in architecture and would get work remodeling homes and businesses. From him, I learned about architecture having spiritual and emotional themes that can be communicated through its design. He showed me how interior spaces need to guide or inspire you to move through them. A building should celebrate its functions in the most natural way possible. For example, one of his simple mantras was that restaurants should be designed in such a way that it’s intuitively obvious where the bathroom is. It may sound silly, but when you apply that principle to all the other functions of a house or a business, the functions become an integral part of the design. His perspective made the famous comment by American architect Louis Sullivan “form follows function” very real to me.

Painted Spatial Depth and Tracking a Tennis Ball’s Trajectory

For a few years now, I was doing art full-time, nine months out of the year, and not practicing tennis. Two or three weeks before the Dutch tennis season would start, I would go into intensive physical training, like running on sand or running up a building’s flights of stairs until exhausted. Normally, pro players practice 3-4 hours every day on court, including additional stretching and conditioning. Even though I hadn’t been playing for months when I got on the court, I could very easily track the ball. Once the server served, I could see the ball like it was in slow motion. The only explanation I have for this is that I was training my eye 24/7 on spatial depth in painting and refining it to such a degree that when I played tennis, my spatial acuity was off the charts.

No one was more shocked than I that in the pro tennis club competition I beat players with world rankings: Humphrey Jose (#123), Louk Saunders (#98), and Ramesh Krishnan (b. 1961, #23). Ramesh would go on the quarterfinals of Wimbledon, only a few weeks after I beat him. Note: I listed their highest world ranking, but not necessarily at the time I beat them.

34 Playing on the Metselaars’s center court in 1982. Photo: Marian Laudin.

35 Dagny, 1982, oil on linen, 20x18”.

It was painful to destroy the painting of Dagny in her office setting. At the time, I was caught between modernist expressive, gestural painting and realism, and Dagny was right in the middle of that transition. The painting had an insurmountable problem, and when I realized I didn’t know how to solve it, it was better to just cut my losses. For these few years, I was focused on character, so I simply refined her face more realistically and added it to my series of portraits. Jennifer Trainer posed, with the twist of merging her features with my mind’s eye of what Dagny looked like. Behind her, you can see the sketch on the wall of a face. In Atlas Shrugged, a scene describes a portrait sketch that was her ancestor that founded the railroad, Nat Taggart, and for that, I used a sketch I did of Rob.

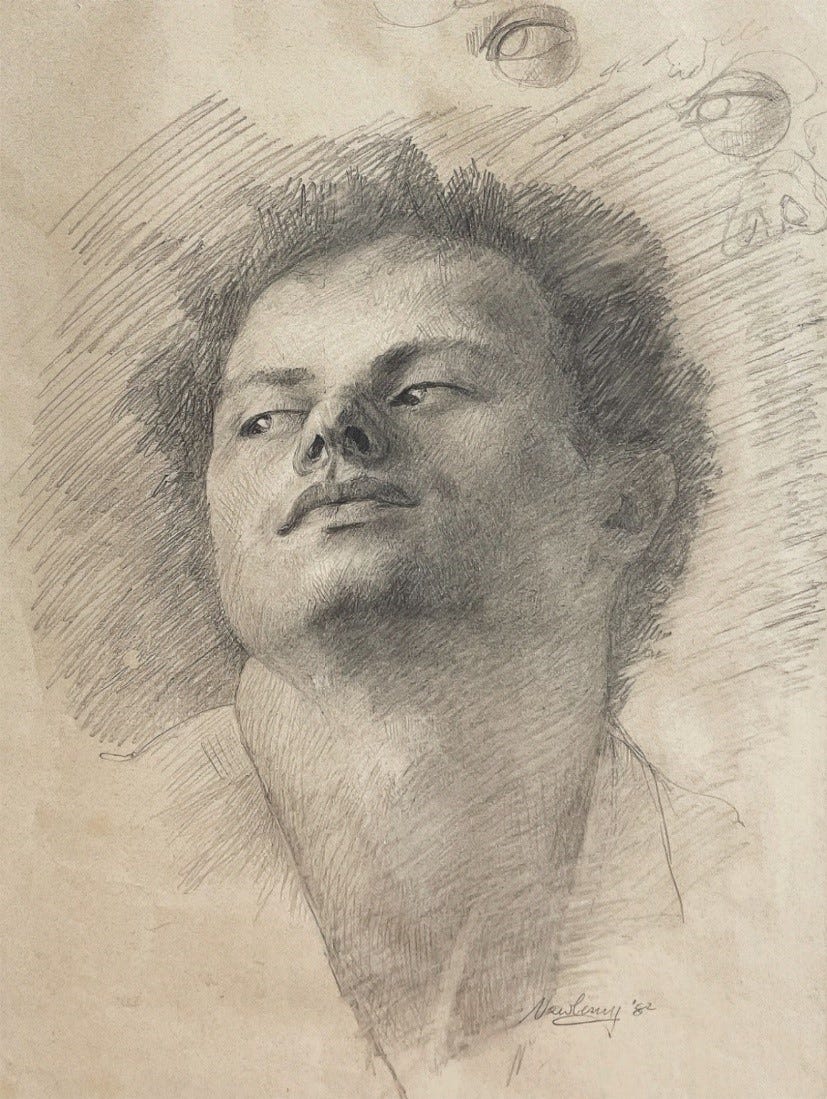

36 Rob as Nat Taggart, 1982, graphite.

I originally did this sketch of Rob's face to be the central character in my epic project, Individuals’ Revolution, and then used it as reference for Dagny Taggart's ancestor, Nat.

37 Portrait of a Young Man, 1982-3, oil on canvas, 40x34”.

The Portrait of a Young Man was a painting I started in Holland but completed in New York, and Peter Duble, the romantic interest of Jennifer Trainer, kindly posed for me, as well as for many of the figures in Individuals’ Revolution. Peter was born with a blood vessel problem, and in his 30’s, he died from a brain aneurysm. At a young age, he knew that he would die young, and he lived his life with such a ferocious intensity—it was magnificent to witness and an inspiring example of living life to its fullest. I was honored he posed for me.

Bronze Portrait of Lynia

When I was a child, I made a plasticine sculpture of Venus de Milo, about 4 inches tall, which my grandmother, Edna, always displayed in her living room. I also sculpted a portrait in college, now lost, but it was fairly realistic. The portrait of Lynia is my third and last sculpture, so far. I loved creating a sculpture in the round, capturing all the different angles of the face. Two bronze casts were made of it, one owned by Lynia and the other whose whereabouts are unknown. It was a great experience for me, but I also didn’t feel that I was really a sculptor. There’s a lot of work involving the casting process and the very scary process of the lost wax technique, where you cover the clay sculpture with a plaster mold, then dig out the clay, leaving the negative. Then you pray that when you pour the molten bronze, it will resemble your original clay sculpture.

38 Portrait of Lynia, 1982, clay.

39 Portrait of Lynia, 1982, bronze, left side.

40 Portrait of Lynia, 1982, bronze, right side.

41 The Sculptor, 1982, oil on linen, 42x64”.

The Sculptor

I love all my work, but one of my favorite paintings is The Sculptor. It was tremendous fun to paint a visual play of a sculptor sculpting a self-portrait in clay. The setting is in the sculptor's studio, where the sculptor is contemplating their likeness in clay. The painting echoes the sculptor's face with that of the portrait.

42 A few pics of Lynia Zaaijer and me, around around 1982. Photos by Marian Laudin.

Man from Manhattan, Self-Portrait

43 Man from Manhattan, 1982, oil on linen, 42x62”.

On two different occasions during my commutes between The Hague and New York, I lived in Staten Island. The ferry trip between Staten Island and New York City was always a spectacular experience. It was breathtaking to see the Statue of Liberty and slowly approach Manhattan.

Man from Manhattan is a self-portrait with the Manhattan skyline in the background. I'm very happy that I painted and documented it. I am dressed up in the portrait, which I rarely do, only for special events like art openings, weddings, or funerals. One exception is that I would get dressed up if I was going to visit contemporary galleries. I wanted to see how they treated me if they thought I was a potential buyer. It was amazing how nice they were. If I went there in my studio clothes, they treated me like I was a plague.

You'll notice that there's Greek writing on the tanker ship: Ktema es aei, which can translate to "universal art lives forever." It was a device I was using, which was kind of cheating; I was sneaking messaging into my paintings that was very important to me but wasn't dramatically conveyed through the painting. For instance, including the book of Vermeer in The Woman in Blue, or the copy of Las Meninas by Velasquez in The Writer and the Artist. It's the artist’s version of a writer telling an audience that a character is noble or evil, instead of showing them to be such. Once I understood I was doing this, even if only slightly, I doubled my efforts to correct it by dramatizing the visuals and getting them to convey ideas and emotions that were important to me.

Throughout these years, I was a walking explosion of passion. There was an outpouring of feelings of adventure, love, and a ruthless drive to create the best art I could, and then push even harder. It was an intense form of hero worship, not of humans, but of life itself.

Though my life-sized figures were characterized by portraiture, I didn’t want to limit myself to that. While I learned a lot about technical realism in painting, I never felt that I was solely a realist. Realism and portraiture were not the end point for me. This period was coming to an end, and I was ready to embark on a new course that would express my whole being—a new kind of romanticism.

One of the things that profoundly touched me about Ayn Rand’s novels, was that her heroes were really tough—driven producers and creators—who pursued their aims passionately and succeeded in both work and love. They were not the romanticized versions of a lost cause, they were a different breed: the creator, the individual.

44 Jennifer Trainer, center, Peter Duble on the right, and me on the left. Around 1985.

While I was living in New York in 1982, Ayn Rand died. Jennifer and I wanted to pay our respects, so we attended the public service. There was a very large line of a few hundred people waiting outside to view the casket, and apparently most of those people knew each other. There was a familiarity and a sense of community that we didn’t know existed. The reception area was a small room with about 8 chairs, the casket, lots of flowers, and 3 or 4 people sitting in the chairs as a line of people briefly circulated through the room and left. Jennifer and I wanted to spend more time, so we sat down in two of the free chairs. We must have stayed for half an hour, absorbing the atmosphere and watching the people file by. We did get a strange look from the person sitting in the other chair, who I would later find out was Leonard Peikoff, and the novelist Kay Nolte Smith, who was just beaming at us.

Individuals’ Revolution

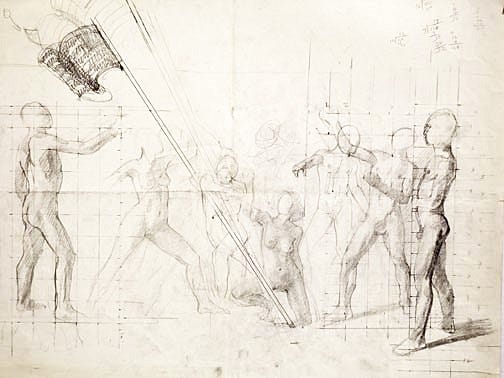

I was burning with a desire to create this new romanticism for my work. I wanted to create a massive painting, like those you see in the Louvre from the 19th century. I came up with the idea of the Individual's Revolution, with the background of a destroyed Washington, DC. The painting would be about 14 by 10 feet. I have included three of my concept sketches of it.

At the end of their workday, either Peter or Jennifer would take the Staten Island ferry from their workplace at Wall Street. They would then pose for each of the characters in those drawings, except for the kid that I made up. It required a tremendous amount of time and effort, considering each pose was two or three hours of work with the model. Imagine them working an 8 or 9-hour shift, then commuting to Staten Island, posing for three hours, and getting home around midnight, just to help me with my project.

I knew that creating a realistic solitary figure in painting could take me six months. Doing a massive painting with several figures, placing each figure in spatial depth, would take me three to five years. Additionally, any glance at the art world told me that there would be no one to buy it, and no museum would take it. It would be a massive undertaking with zero funding. I abandoned the project, recognizing that it was not the right time for me.

As a side note, every one of my art projects was done out of love, with no commission. So when a painting took me 6 months, I was paying for those 6 months without any guarantee that I would make a sale—a practice I've continued to this day, with one exception: the portrait Ralph, which I will discuss later in the book.

45 Studies for “Individuals Revolution,” 1982-3, graphite.

Promethia

46 Promethia, 1982, oil on linen, 78x58”.

My romanticist breakthrough came with the life-size painting of Promethia. Jennifer Trainer posed for the figure. The building depicted is the UCSD Library in La Jolla, CA, where I grew up and got to witness its construction. The background features the Palm Spring desert area with the San Joaquin Mountains in the distance. Currently, I live up in those mountains in the town of Idyllwild, California.

I always felt boredom with meaningless abstract sculptures in front of buildings or in their lobbies. Well-designed architecture is such a magnificent result of problem-solving, from technique to the expression of the human spirit. Abstract sculpture is neither. At a minimum, its aesthetic value is that of haphazardly tossing a placemat on a table.

Great architecture, like Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings, should have magnificent figurative sculptures in their entrances. His Taliesin East studio in Wisconsin was adorned by a copy of the Nike of Samothrace. Which is suggestive.

With Promethia, I was trying to project into the future what I would like to see as the integration of nature, architecture, and figurative sculpture. I tried to make the painting look as believable and real as possible, but it was a figment of my imagination, integrated with real references. In a way, that's what I see the magic of romanticism as: taking an optimistic vision and making it feel believable, real, and accessible to people, thereby making their hopes and dreams feel real and possible as well.

Manhattan at Night

Who knew that doing a painting of Manhattan would turn out to be such a bittersweet artwork? The stars of Manhattan at Night are the twin towers. Creating the project was fascinating. I'd taken a daytime photo from the Staten Island ferry of the Manhattan skyline, and I used that as a reference for the placement of all the buildings. Once or twice a week, I would go into Manhattan to visit friends, see the galleries, and do New York stuff. On the way back, at night, I would study all the shimmering lights, remembering which were warm colors and which were cool colors. With the night scene committed to my memory, I transformed the realistic composition sketch into a nocturnal scene. Anytime I had problems with the painting, I would take a trip to New York and come back at night to recalibrate my understanding of the lights.

47 Manhatten at Night, 1983, oil on linen,

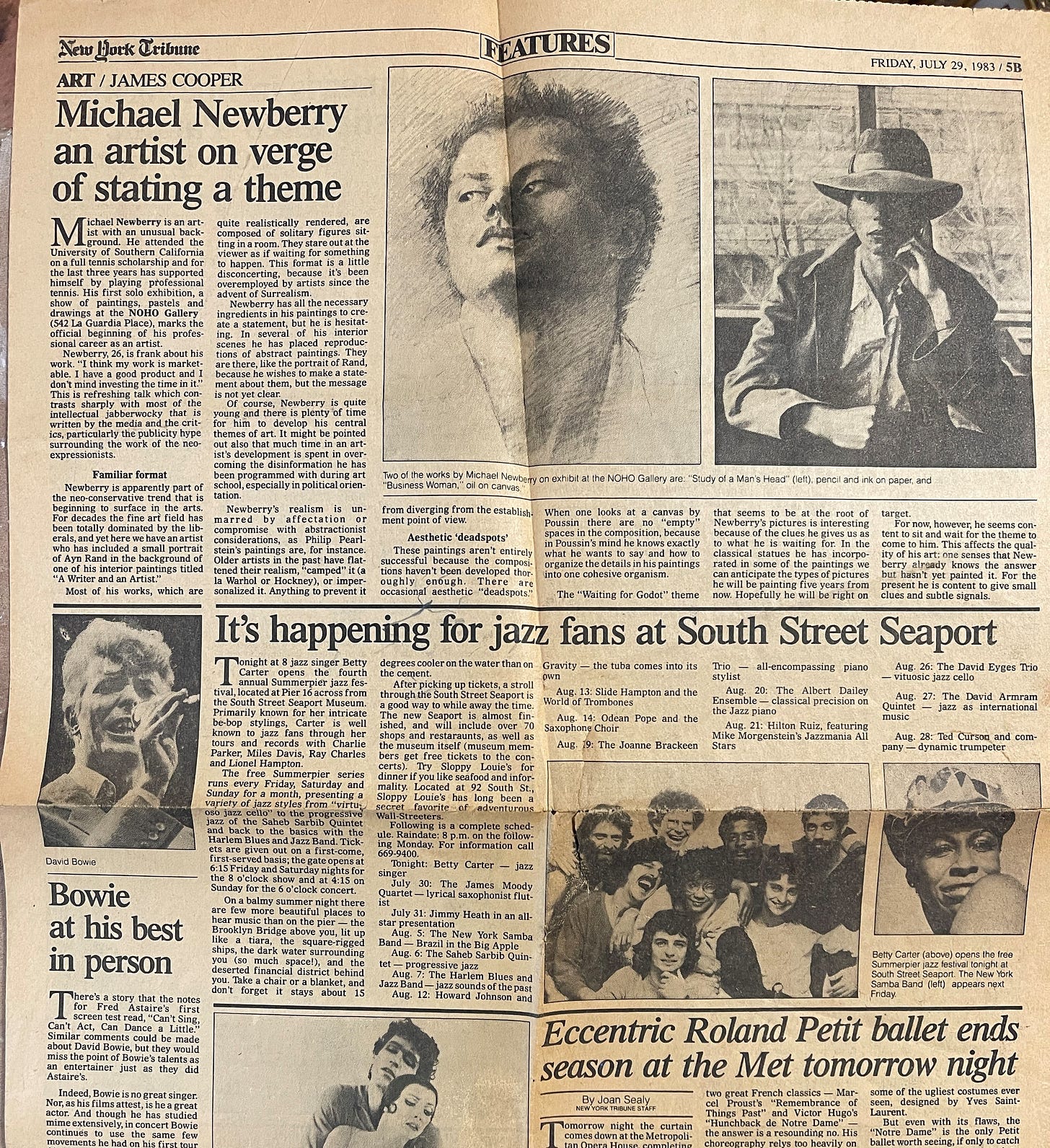

Solo Show at the NOHO Gallery

For a year, I’ve been planning a show at the Noho Gallery. It was a communal gallery, and they let me rent the space at the end of July 1983. I did the whole nine yards of mailing press releases with 8x10" glossies of artworks, sending invitations, and giving plenty of notice. I was worried that no one would come, but several people started to arrive. I believe about 400 people visited the gallery that night

I sold about $16,000 worth of work, most of them on terms that people could pay me a little per month. The portrait of the young man sold, as did the woman in blue, the skyline of Manhattan at night, and several drawings.

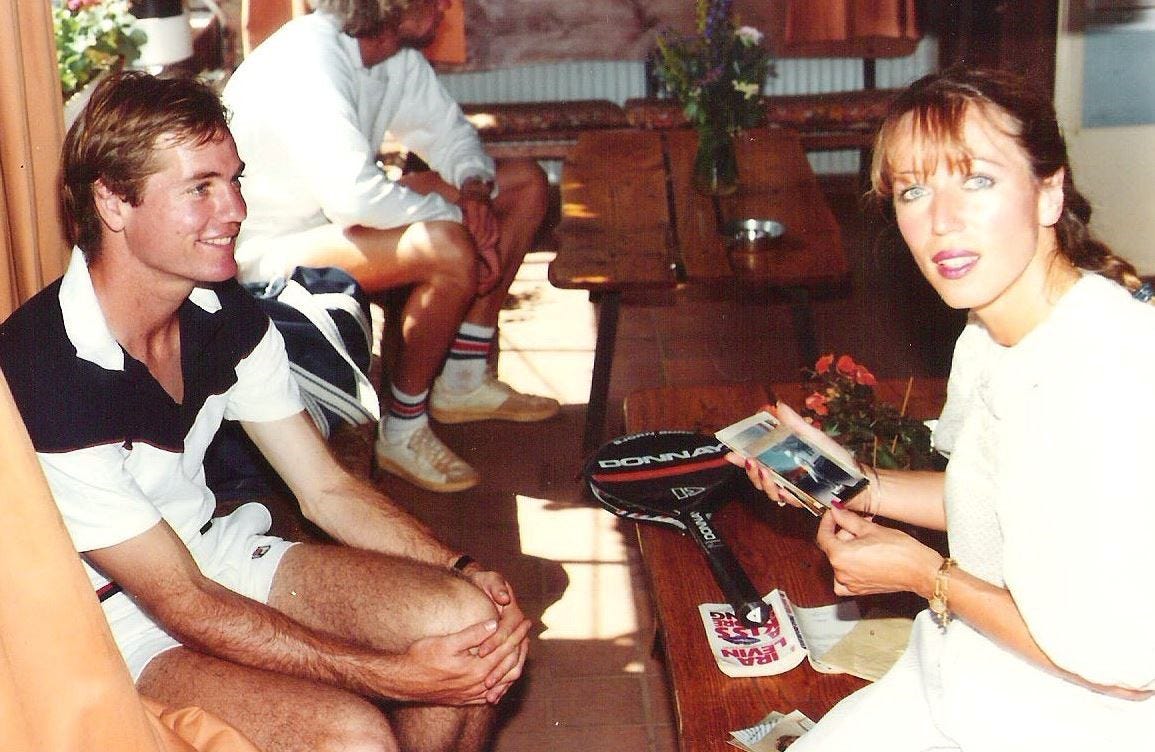

Lynia and Rob came from Holland, and Jennifer and Peter were also there. Jennifer bought Woman in Blue. Another attendee was Jennifer Jordan, a journalist and writer, who would become a collector. She wrote a book titled Savage Summit: The True Stories of the First Five Women Who Climbed K2. My sister, Janet, and her husband, Frank Wright, attended, and Frank arranged for a limo to transport me to the opening.

The next day, there was a big review by James Cooper in the New York Tribune. I got top billing on the art's page, with a review of David Bowie at Madison Square Garden underneath. “Of course, Newberry, 26, is quite young, and there’s plenty of time for him to develop his central themes and art…Newberry’s realism is unmarred by affectation or compromised with abstractionist considerations…the ‘Waiting for Godot’ theme that seems to be at the root of Newberry’s pictures is interesting because of the clues he gives us as to what he is waiting for. In the classical statues he has incorporated in some of the paintings, we can anticipate the types of pictures he will be painting five years from now. Hopefully he’ll be right on target.”

48 The New York Tribune, James Cooper’s review of solo show in New York, July 29, 1983.

Cooper’s review was quite perceptive. With Promethia, I felt like I broke through to the kind of romanticism I wanted to create in future works. But there was one other nagging element that I was curious about. I had this feeling I wasn’t quite where I wanted to be. With that in mind, I reviewed the timelines of my favorite artists like Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Gogh, and Michelangelo. Michelangelo had his breakthroughs early, in his teenage years, but he had been apprenticed to master artists as a child. Rembrandt did some so-so paintings until his late 20s, as did Vermeer. Van Gogh, on the other hand, was around 30 when he clicked. So, I noticed that great painters generally hit their stride somewhere around 30. At 26, I had a few more years to reach the level where my work would blow me away, as did those artists' best works. With a mixture of excitement and nervousness, I redoubled my efforts to try to make some masterpieces.

With the next year's expenses covered, I said goodbye to pro tennis in Holland and remained in New York, where I shifted into high gear and drove with the pedal to the metal and devoted 100 percent of all my effort and time to art.

Wow, your artwork is always incredible; I agree that studio painting is very special. You have an excellent way of capturing light and people. Thank you so much for sharing your story and art!

Loved reading about what you took on /learned from your fellow artists, sister and models - how they added to you and your art, almost shadowing your explanations of the techniques and colours you used in your pieces.

Also, loved you pointing out what I refer to as "Easter eggs" in your paintings, the little tributes to the great artists and ideas you feel important.

So awesome to have these insights shared by the actual artist and not guessed at by historians and the like.

MESMERIZED by the Lady in Blue. 💙