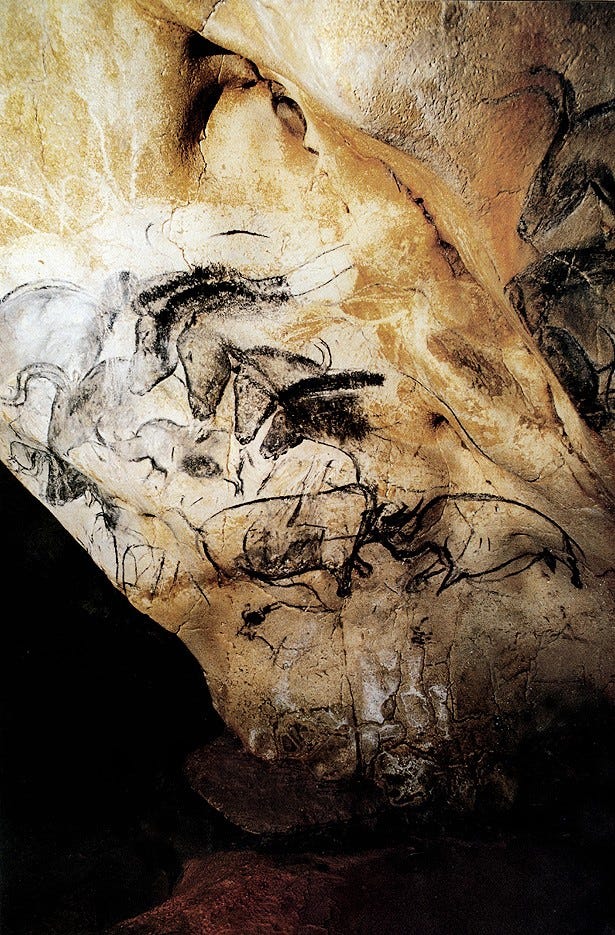

Figure 2, Horses’ Heads at Chauvet Cave, France, circa 35,000 BC. photo: Bradshaw Foundation

Doorway to Self Awareness

The threat of storms, dangerous animals, strangers, and hunger would have kept our earliest human ancestors in a constant state of apprehension. Nothing to do but to put out one fire after another. Track prey—the bigger the better—for feeding family and the group, but dangerous. Gathering food, fortifying living areas, and protecting children and helping them learn. Sex would have been a welcome (or under threat an unwelcome) part of existence. Sleep, however, would be uneasy as two powerful needs, self-defense and rest, made conflicting demands. Once awake the process repeats itself: observation, focus, and taking actions for survival. Time would never stop as everything would be in a constant state of flux.

As with other animals humans would have keen perceptions with the ability to focus and distinguish a singular animal from the herd. They would have all the optical acuity of a cat zeroing in on a mouse, rarely being confused by visible leaves rustling in the wind. This sensory skill is not unique to humans, but at some point something changed and humans began to conceptualize their vision. The early humans began to linger on visual cues: the shadow cast by a waving hand; a glimmer of light flashing on a creek's water surface; a row of faces in profile. Yet none of these things would serve their immediate need for survival.

These were moments when time stopped. Not exactly self-awareness, but a moment when early humans observed visual characteristics of things. Where a cat might momentarily pause seeing a mouse's cast shadow, but then swiftly direct all its energy on the thing, a human would periodically focus on the attributes of the cast shadow and notice such things as a moving shadow on the rump of a bison, a line that showed the edge of a horse's head, a patch of light on a lion's jaw. There would only be a moment to notice: it wasn't like the lion was striking a pose for the audience.

When human observers were ahead of the game, sitting outside, fed, feeling safe, maybe a little sleepy, they might glance at the cloud formations, much like we do as children. And all of sudden, something in the shape of the clouds reminded them of the bison's body. Fascinated, they would have spent minutes looking for other recognizable objects in the clouds, like lizards, faces, and other animals. They would have known clouds were mist-like stuff, and they would be certain that they weren't real animals. But the images in the clouds would give them time to notice similar patterns of lights, shadows, and edges. These humans, unlike other animals, were abstracting visual attributes. It must have been unsettling because it was time, effort, and focus that had nothing immediately to do with the needs of life. These humans were on the cusp of being artists.

Once seeing and abstracting these patterns, they would begin to see with new eyes. Instead of this strange focus lasting for a split second, it would be an ongoing optical phenomenon. Now everything in their field of visual would be made up of noticeable patterns of light, shadows, lines, and shapes.

The first artists would have likely sketched images in sand or dirt with a stick, adding contour trying to reproduce animals through visual patterns that currently obsessed them. It would be undoubtedly annoying for these early artists, after spending hours drawing an image in the dirt, to come back later and find it had blown away. I can see them going in search of a friend to show them the wonderful thing that they had made. All that magic gone and wiped out of existence.

The properties of charcoal and clays mixed with colored minerals bound by spit and animal fat would have been familiar to them, the first uses were for coloring themselves, hides, and tools, not yet for painting things on cave walls. Imagine a den fire projecting dancing lights, shadows on the surface of cave walls. Similar to the images seen in the clouds, there would be some shaded contours on the curvy cave walls that would have reminded these artists of a bison leg, head, or some other animal part. With just a little more shadow or line would it be possible to complete the form? Would the charcoal work? Or clay?

Those first drawings on the walls would have had a powerful effect, not the least of which would have been permanence. The spectacle of them would be there tomorrow, the day after, and for many more days to come. The images were unchanging, held still. In a world where everything changed every minute of the day, the artwork on the walls was fixed forever. The experience of the audience of these first artworks would have been magical, it would be the introduction into the human psyche of contemplation—the doorway to self awareness.

Magnificent Spirit Animals

The conceptual leap is extraordinary! Abstracting three-dimensional visual chaos into categories of tone, shadow, light, and form and then transforming those attributes, reassembling them, to recreate animal images through the single sense of sight is perhaps the greatest achievement in humankind's long list of exceptional firsts.

The effect of the viewers would have been mesmerizing, an unfathomable spectacle of the disconnect of the paintings being real and not real at the same time. The images would also have the haunting insistence of having once been seen could never be unfelt or unseen. The images would reappear without notice in the mind's eye, like a pop song, dominating space in their brains.

For the artists and viewers these images would have been both terrifying and exhilarating. Exhilarating as a magical power to turn stone surfaces into these magnificent animals and terrifying because they were not only not real but a direct challenge to their reality of living moment-by-moment addressing real needs for food, shelter, and safety. The art would have acted like an addiction to some, pulling them away from the necessities of life, spending senseless time in a cave making stuff up.

Figure 3 Chauvet Cave Horses' Heads and Michelangelo's charcoal sketches, 1530, from Medici Chapel of the Basilica di San Lorenzo.[1]

Just as the artists were abstracting chaotic visual stimuli, they were also isolating certain types of subject matters. In the Chauvet Caves, located in the Ardeche region of France, we find paintings of powerfully massive animals. The meekest—such as horses, bison, and deer—could kill a man with a gentle tap of its forehead or hoof. Many were ferocious—such as cave bears larger than today's grizzly bears, lions, mammoths, panthers, and rhinos. Can you imagine walking around a boulder and coming face to face with a massive bear? Were the artists facing their fears by painting dangerous animals? Were they also painting their sources of protein? Were their lives dominated by interactions or possible interactions with these animals? There are over 420 images of animals. In size, they dominate the Chauvet Cave walls.

In the nature of art, artists make a statement about the subject matter they choose to paint. They are saying in effect: "This thing, right now, is more important than anything else." We can surmise that these large animals were the main focus in the minds of the cave artists and presumably in the audience. We don't see mice and other small prey; there is an owl, but no other birds, some of which would have been sources of food, but not depicted. Why? Not much of a challenge? Not a source of community banquet celebration? Not a threat? Not important enough to consider?

An interesting aspect about these adversarial animals is that they are not painted as monsters. They almost look benign. It is as if the artists are focused on showing what they objectively look like. Almost scientifically. They are not growling or flashing their fangs. They almost look domesticated, which in most cases would have been impossible. The calmness of the artists' perspective is astounding. Were the images something of a guide of what to watch out for and what to pursue? One must wonder if there were stories told after dinner of the exploits and tragedies involving the animals.

You have heard it said that artists’ artworks are like their children. That is not exactly right, but there is a sense of owning one's art. There is a feeling of possession not only of the work but the subject as well. In real life, lovers don't always reply the way you wish them to, and a lion doesn't purr when you pet it. But when an artist paints a person or a thing, the artist is in control of the subject: it does what he wants it to do. Could these benevolent cave paintings be like casting a spell on the animal advisories? Or making the subconscious statement "I own you!"? Or held forever in a time capsule?

Beside the monumental animal depictions are scores of handprints and stenciled hands. Some of the prints were used to fill in the color of the animals like a brush or sponge. But others were definitely leaving a literal hand impression. They are not artworks in the same way the drawings of the animals are, as there is not the conceptual turn of thought. Drawing and painting are showing us how the artist felt, saw, and thought, while the hand marks are like graffiti—a form of "marking" the territory.

These first occupants of the Chauvet Caves would die out before the walls could witness the development of equally impressive drawings and paintings of humans.

[1] It is worth showing these sketches side by side. It is easy to see the Horses' Heads foreshadowing Michelangelo. They share line work, gentle shadowing of the forms, and overlapping. Surprisingly not that far apart, yet it is prehistoric art next to one by one of the greatest artists of all time.

5.0 out of 5 stars A New Platform for the Figurative Art Movement

Reviewed in the United States on April 26, 2021

In the last fifteen years, it has become clear that the world scene for artists has undergone a dramatic shift. Thousands — tens of thousands of figurative and representational artists are practicing around the world. They have been enabled by the slow return of the art atelier — what is now called the Atelier Movement. Unfortunately this movement is only starting to get its advocacy legs. Despite world-wide grassroots art-making, we have yet to see fresh, excellent figurative art in museum shows, or see high-dollar sales.

Michael Newberry is a life-long artist, who has often advocated for the figurative arts through philosophical articles and reviews. He speaks plainly and from the heart but with a razor sharp knowledge of art history and theory. This book is a clear-headed contemplation of art history and its relationship to our evolution and humanity. And it offers a moral platform for figurative artists to advocate for themselves while bringing beauty and humanity back into the arts.

The first section of the book is a contemplation of the role that the development of figurative art played in our ancient history. Newberry’s point is that the psychological function of art is multi-faceted and complexly intertwined with our evolution. He talks as much about the experience of creating art, as the act of observing it. Newberry carries us swiftly through time, picking and choosing advancements in the successful representation of the figure. He always pays attention to the subtle and beautiful emotional experience of the art, never forgetting that we are not talking just about form.

The second section of the book is a candid stare at the dark side of art history, at those who have sought to destroy art. This was all new information to me, and I wonder where a modern art student would go to find it.

What is most essential to Newberry’s thesis is his clear understanding of the impact philosophers have had on the history of art. In particular, he contrasts the Ancient Greek idea of eudaemonia, “the ultimate state of the noble soul” as described by Aristotle; with the views of Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant. Newberry discusses several works by 20th century artists such as Pollock, Christo, Whitehead, McCarthy, and Duchamp that exhibit Kant’s notion of the sublime in their conveying of “horrific insistence on negative emotions like wrath, despair, and violation.”

There is a clear headed strength in Newberry’s words. He is a great figurative artist who is commentating on postmodern art. He is like a man staring down a vicious beast, and without flinching, is able to subdue it. And in this strength he is giving power to figurative artists everywhere.

The third section resumes the walk through history, discussing those who have made unique contributions to our technical understanding of color and light. Newberry concludes the book with a discussion of living artists who, through their work, are continuing to push art forward. Although Newberry is a brilliant artist himself, he keeps the spotlight on his contemporaries.

Newberry offers a new vision of the sublime that ought to become the rallying cry for the figurative art movement: "Art integrates senses, emotions, and thought. The sublime in art elevates our sensory experience, heightens and taps our emotional potential, and furthers our knowledge. The sublime in art can give us a moral to the story, a stance toward living. At its best, the sublime in art inspires awe in our human potential and awakens our desire to evolve as a whole being and as a species."

Figurative artists are knocking on the door of the art world. The modest, clear, and compelling thoughts of Michael Newberry show us that we have a moral justification to break down the door and move in.

8 people found this helpful

Michael your work is always so intriguing and inviting to read. While in France did you visit the Cave drawings? I think that would be a fascinating visit. And placing them next to Michangelo’s work is totally unexpected like Jenn mentioned. It’s a fascinating study from an Artist’s perspective, I’m sure! Thank you!

Whoah, seeing the cave drawing next to Michelangelo is unexpected and really thrilling. I am amazed, what wonderful foreshadowing; what wonderful art and ways of seeing that connect all of humanity through time. Thank you so much for sharing this.