CIA Weaponizing Abstract Art and Its Fallout

Corrupting Media, Foundations, Art Institutions, Reputations, and Artists

I hypothesize that, between 1950 and 1967, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) used abstract art as a PsyOp tool of psychological warfare to undermine the American mind. This was done through their subordinate group, the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), to enable the Agency to manage the American public.

Their problem was how to brainwash Americans who were traditionally known for their clearsightedness, confident independence, and optimism. The CIA chose to undercut those values by creating a psychological disconnect, and abstract art was their tool for doing this.

The CIA and CCF used museums, philanthropists, foundations, magazines (both popular and literary), artists, musicians, critics, and intellectuals for their propaganda. Their stated aim was to win the cultural cold war against the USSR; anything that was "anti-communist" was unimpeachable. Their idea was to promote new American art, literature, and music, with the slant that it represented freedom. This art, specifically abstract art, broke fundamentally with European and Russian art. The CIA's intellectuals might not have known that they were subverting humanity by rejecting the cultural values of Western Civilization.

The irony is that, by the time CIA came into being in 1947, the USSR was completely broken by poverty and famine as well as being morally broken by genocide; it posed zero threat to America, cultural or otherwise. Yet the CIA incomprehensibly played up the USSR's threat and its wealth. The CIA, through the CCF, then covertly used government funds to run a PsyOp—not on the Russians but on the American and European public. The USSR was not a threat to America's dominance; America was already an exemplar of freedom, wealth, and success. The cold war was won before it started, and the US could just let Americans be goodwill ambassadors naturally, by way of such things as the huge appeal and influence of American films. Yet the CIA secretly persisted in extravagantly promoting abstract art.

CIA's Congress for Cultural Freedom Impact

The brainchild of CIA operative Tom Braden, the CCF covert operations were led by Michael Josselson and CCF secretary-general (and Russian composer) Nicolas Nabokov, first cousin to author Vladimir Nabokov. Frances Stonor Saunders, in her exceptionally good book, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, writes:

At its peak, the Congress for Cultural Freedom had offices in thirty-five countries, employed dozens of personnel, published over twenty prestige magazines, held art exhibitions, owned a news and features service, organized high-profile international conferences, and rewarded musicians and artists with prizes and public performances. Its mission was to nudge the intelligentsia of Western Europe away from its lingering fascination with Marxism and Communism towards a view more accommodating of “the American way.”

Without irony, the CCF promoted the "American way" through the recent development of abstract art, which was nothing like the enthusiastic, optimistic, goal-directed spirit that exemplified much of American life. It was also essential that the CIA and CCF could not be seen as the funders. They had to give the impression that all the hoopla around the new American art was a magnificent, spontaneous cultural development sprouting freely worldwide and not the propaganda that it was. Tom Braden confirms this in his article for The Saturday Evening Post, May 20 1967:

And then there was Encounter, the magazine published in England and dedicated to the proposition that cultural achievement and political freedom were interdependent. Money for both the orchestra's tour and the magazine's publication came from the CIA, and few outside the CIA knew about it. We had placed one agent in a Europe-based organization of intellectuals called the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Another agent became an editor of Encounter. The agents could not only propose anti-Communist programs to the official leaders of the organizations but they could also suggest ways and means to solve the inevitable budgetary problems. Why not see if the needed money could be obtained from "American foundations"? As the agents knew, the CIA-financed foundations were quite generous when it came to the national interest. http://www.cambridgeclarion.org/press_cuttings/braden_20may1967.html

Art as PsyOp

By its nature, art is a PsyOp, perhaps the most advanced PsyOp that ever existed. There is a light-hearted spy television series, Chuck, that turns on the premise that vast amounts of knowledge can be visually embedded through a revolutionary technology into the human mind, thereby transforming the recipient into a superhero. It seems ridiculously far-fetched, yet, that is exactly what great art does to you.

Art is a much more powerful tool than most people realize; it is the key to human evolution, as it integrates passion, perception, and thought into an indivisible whole. It can ignite one's most passionate belief in oneself and fuel their conviction for a flourishing future. Surprisingly, art is the ultimate in covert activity because people generally are not aware of how art works its way into the human psyche, often resulting in intense feelings. As you focus on an artwork, the embedded concepts in the artwork enter the complex network of your mind, tapping into your physiology (via sensual perception), emotions, and thought processes.

The CIA took this power and reversed it; instead of empowering people, they used senseless abstract "art" to subvert them. To understand what I am driving at, let's compare two Rembrandt paintings with a Pollock painting.

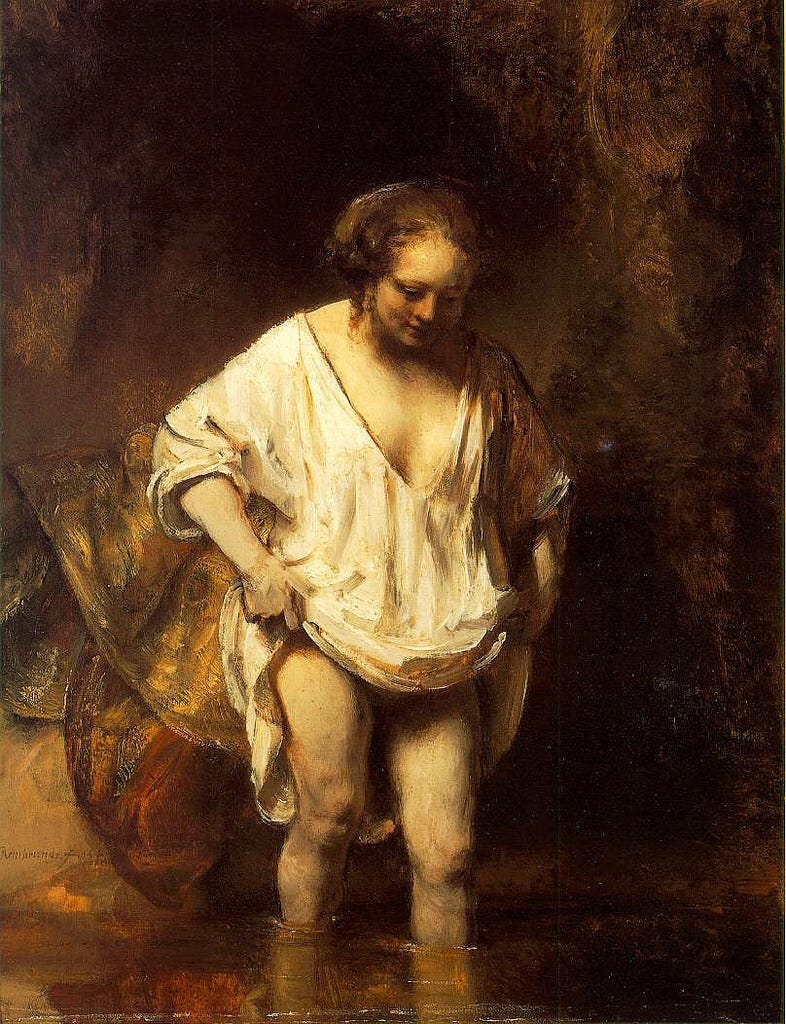

Rembrandt, A Woman Bathing, 1654, National Gallery, London.

Rembrandt's Woman Bathing is thought to be of his mistress Hendrickje Stoffels. She is wearing a white chemise that hangs loosely about her shoulders, which she has gathered so as not to get it wet. By doing so, she has exposed her upper thighs to the sunlight. If she were to lift her chemise a little bit more, we would see her crotch. She is carefully stepping through the stream. Her head leans over; perhaps she is looking at her reflection in the water. The slight curve of her mouth, with the nuanced shadowing of her cheek, gives us the sense that she is thinking pleasant thoughts. Perhaps she has just made love with a lover or is getting ready for a romantic evening?

She is powerfully lit by a golden light and with equally powerful musky dark shadows that mold her forms—they dance with confidence on, over, and around her. Rembrandt not only created a hierarchy of light, which excites our eye to move from light to light carefully measuring each brightness, but he also is moving the light effects through space. He does the same for the shadows; notice the ivy-covered tree trunk over her left shoulder and how that feels like it is six feet or so behind her. Also notice the terribly rich embroidery of her wrap that is haphazardly placed on the bank. There is a fascinating contrast between the wealthy garment and the modest chemise, giving us the sense that she could be both royalty and a natural woman.

The light optics are as advanced as any understanding we have of reflections, refractions, and the nature of light and shadow. Notice the reflections of her calves in the water. You can see how their optics are different according to their location in space and in relationship to the light on her legs.

She is the main feature of both the setting and the composition. From this painting's perspective, she symbolizes that individuality and womanhood are the center of the universe. Rembrandt arranged the elements of the composition for both realism and as a powerfully abstract arrangement of large forms of darks and lights; the abstraction here is used to organize subgroups of details inside larger manageable groups. This allows us to view the big arrangement of shapes in which she is prominent and to begin to see more, as we look deeper into the work.

In this painting, Rembrandt is showing a loving vision of his mistress; the intimacy is unselfconscious, easy, with hints of eroticism. It is a beautiful moment of a woman leisurely interacting with water in a secluded place, which also gives us a sense of her freedom and confidence in being in sync with nature. Rembrandt is using his love of humanity—of this woman in particular—and his tremendous understanding of visual science to share his view of humanity as beautiful, free, successful, and natural.

The positive PsyOp here is that Rembrandt shows us what love, freedom, and individuality looks like. This vision enters our subconsciousness and triggers the pathways of our feelings of passion, perception, and thought. We are not conscious of all of these connections but our being absorbs them and stores them away in our DNA memory. At different times in our life, we will instantly recall this painting, which will then give us a reminder of what love, freedom, and independence look like. We can imagine a warfighter shoring up his confidence by recalling this image, or something like it, which, in turn, spurs him on, knowing he is fighting a just cause.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait in a Cap, Wide-Eyed and Open-Mouthed, c. 1630. Etching and drypoint; 2.09 x 1.81 inches. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This self portrait by Rembrandt is arguably one of the greatest drawings ever made. What is startling is the confidence and absolute ease of the mark-making. It gives us the impression that the energy and excitement of the piece is due to freedom of application. That is partially true, but the genius of the drawing is that every mark represents an aspect of light, form, facial feature, spatial depth, and tactile quality. Tremendous skills are so ingrained in the artist that the results arrive as if by a magical wave of the artist's hand. This is mastery that shows us the psychological state of freedom.

Because of drawings like this, some people believe that spontaneous mark-making is the source of great art and not as a consequence. Some artists believe that if they can draw or paint freely, they can be great artists too. Their belief is that proportion, thought, form, light, shadows, realism, and subject matter should be eliminated because they are too calculated. Instead of embracing the challenge of great art, they reject its fundamentals and are left with angst and frustration—not exactly the attributes of their hoped for freedom.

Likewise, Jackson Pollock, the iconic Abstract Expressionist, rejected these aesthetic values that gave rise to Rembrandt's expressionism.

Pollock used house paint to literally pour, drip, and splatter the paint. There are no shadows, no light, no forms, no depth, and no conceptual use of color. There is a weird negation of ends and means; the painting's subject is drips of paint through the means of dripping paint. Enough to turn any mind stupid.

All art has an audience of humans, and there has to be some connection between the artwork and humanity. So, what are we looking at? It is not a thing like a tree, or a string of wires, it is not hair, or anything human. This painting’s closest connections to real life are, literally, accidental spills. Anyone who has spilled or accidently dripped house paint, viscous liquid, cooking oil, or car oil, will recognize the splattering effects in this painting. This paint lacks a key component of art: the conceptual flip our eyes automatically make when seeing something real from our three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface.

Though it is common to call this type of painting abstract, that would be incorrect. Abstraction is a way of organizing units that have a common denominator; for example, a forest is the abstraction of a group of trees, or a shadow is an abstraction of the things that fall within it. An abstraction is a device to corral things. An abstraction in itself is meaningless. "Abstract art" is an oxymoron.

If we expect to find human values in this work, we can locate one symbolic element: the universe is incoherent and devoid of light, substance, and humanity.

There are films of Pollock splashing and dripping paint without any hesitation on canvas laid flatly on the ground. I remember watching one of these films as an 8- or 9-year-old child in elementary school—an indoctrination that still makes me sick. These films were made to give the impression of a passionate genius at work by dignifying a pissing-like gesture without thought, perception, or heart. Some have equated this to vomiting, but don't laugh or dismiss this statement, as there are contemporary postmodern artists that swallow colored liquid and then literally vomit it on canvases—consequently bypassing all aesthetic knowledge, emotion, and perception.

Clement Greenberg

Knowingly, unknowingly, or as a CIA operative, one of the propagandists for the CIA was art critic Clement Greenberg, who was regularly published in magazines that were covertly funded by the CIA. In 1950, while he was associate editor at Commentary magazine, Greenberg became a part of the CIA-sponsored American Committee for Cultural Freedom.

He was the biggest supporter of Abstract Expressionism. He only had to stay in good standing with the CIA if he included the CIA's theme in his writings: that the "freedom" of Abstract Expressionism was the antidote to communism.

The CIA PsyOp behind promoting Pollock was to send the message that genius is a blustering, nihilistic, crazed artist that is compelled to do senseless acts. They succeeded in confusing the hell out of the general public by undermining their sense that art should be knowable and inspiring. The CIA knew, and was threatened by, the knowledge that real art was the linchpin that empowers humans to feel the full power of their combined senses, thoughts, and emotions. Their evil psyop was to convince people that passion without reason or reality is genius. The bigger the farce, the more they can get away with. Through using abstract art, the CIA would drive a psychological wedge through the soul of not only Americans, but humanity as well.

When I asked my friend and PsyOp specialist, Boone Cutler, what the motive would be for a negative PsyOp, he said, “Manageability...piece by piece.” It is reasonable to conclude that the CIA wasn't interested in winning a cultural cold war with Russia; rather its goal and aim was to make Americans malleable. They didn't have to totally destroy one's values of art. It would be enough to get Americans to shake their heads at the absurdities of contemporary art, question the validity of their art knowledge, conclude that art is subjective, and it is not a crucial value. Succeeding in that, the CIA could then gloat they had undermined another flourishing soul, and there would be one less witness to their pathetic machinations.

Fallout

There have been several negative consequences of the CIA weaponizing art. From the 1960s through the present day, there has been a disregard of fine art knowledge in universities. As in the case of Yale and Harvard art schools, higher education has been abandoning representational fine art in every mode: visual tools of form, color and light theory, subject matter, and anatomy. It is like not teaching grammar or music and then expecting students to be writers and musicians. My first-hand witness of this disintegration of art instruction occurred during my fine art studies in the US and Europe in the 1970s. We are, however, now seeing some art universities re-establishing fundamentals after decades of absence.

Other consequences have been the ways intelligentsia, directors, museums, and schools dissed representational art by cutting off funding, shows, teaching jobs, and recognition for real artists. One can only guess at the thousands, if not millions, of artists that gave up their dreams under those appalling conditions.

Another very sad turn is that the CIA seduced heads of cultural institutions, artists, critics and collectors, among others, by giving them funds, guaranteed sales, recognition, fame, the world’s greatest venues, and the exciting role-play of being a CIA operative—an unrepeatable opportunity to be like James Bond. It’s enough to turn the stomach of any decent person. The fallout has been that the CIA killed the artistic integrity of every single person and cultural enterprise they touched. Now, one wonders if a review in the New York Times is really government propaganda? And who is paying for massive shows of conceptual installations—stuff that no one would ever purchase for their home? Is the CIA actually paying for an auction house sale of a Pollack for over 100 million dollars? Could it be a way for the CIA to launder taxpayers' money?

I grew up in a time when the CIA seemed to be on the side of good people, and they were genuinely fighting for the rights and freedoms of people who could not fight for themselves. It was understood they needed to keep their foreign activities covert; but that was okay because its operations were being used against bad people who dropped gays off buildings, tortured women who had been victims of rape, and turned children into commodities. But if the CIA is using its operations against good Americans, as they have done with their cultural PsyOp, then they have gone beyond Google’s former mantra of “Don’t be evil” and have become predatory vampires of the spirit.

It is very likely that this early CIA covert operation was used as a prototype to expand their powers; and, undoubtedly, they are now using cultural institutions, search engines, news outlets, social media and our phones to spy and manipulate us to make sure that we are, and will remain, manageable.

It has been a relief to know more about this very sad history of American culture and to understand how a key part of this enormous farce happened. These last decades of witnessing the pathetic state of the contemporary art world has been very uncomfortable for me. I knew psychologically that something was wrong: none of the people, directors, events, or artworks made sense.

An antidote that protected me from decades of this aesthetic sham: is seeking the best, loving it, and authenticity. When something, someone, or some aesthetic didn't ring true, I would note the peculiarity and move on without it, which kept my independent mind and integrity intact. It protected me when I did not know all the details of how the art world worked. Now with much more knowledge, I am thoroughly disgusted with these horrible people and institutions.

Michael Newberry, Idyllwild, 1/31/2021

Frame of References:

Saunders, Frances. 2000. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. An absolute must read for everyone interested in art, art movements, political history, the deep state, the methods of America's intelligence services, or black PsyOp. https://www.amazon.com/Cultural-Cold-War-World-Letters/dp/1595589147/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=frances+saunders&qid=1639716921&sr=8-1

Troy, Jr, Thomas M. 2002. CIA historian on CIA's site: Review of Frances Saunders's The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. PDF. https://www.cia.gov/static/79f632b1778cb8189328b7f9c4682bf3/The-Cultural-Cold-War.pdf