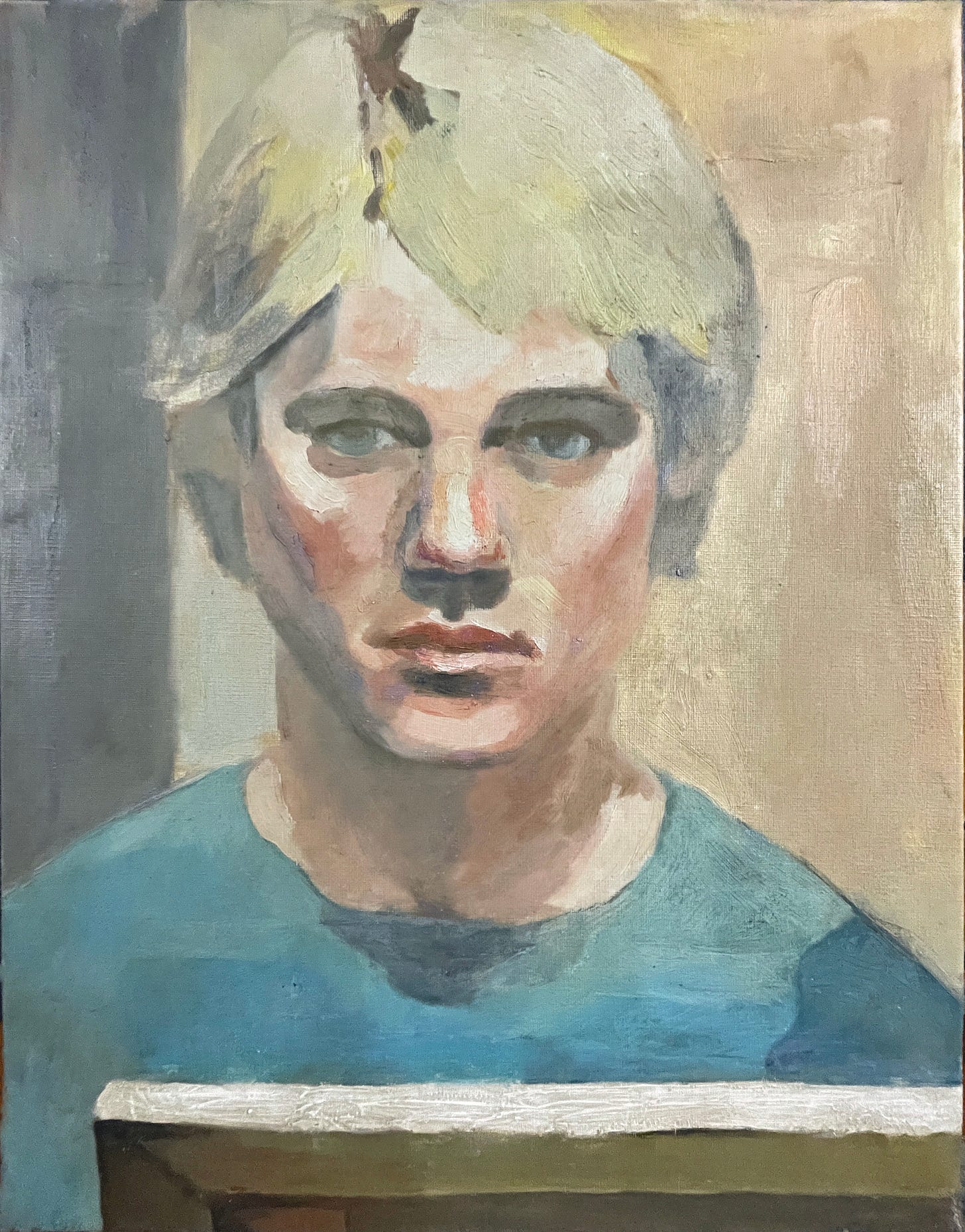

10 Newberry, Self-Portrait, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 17.5x13.5”, The Hague, Holland.

In May of 1977, I was cleaning out my mid-Wilshire Los Angeles apartment, making sure I'd get the cleaning fee, when a package from my aunt Gladys arrived. I had never met her and was surprised to see inside the accompanying card a check for $1000, along with a note wishing me a wonderful summer trip. She also included a coffee table art book of Japanese mythologies and mentioned that her deceased husband, uncle John would have liked for me to have it. The Japanese connection was a dark and painful element in my family's history.

Within days I was leaving for Europe to play their tennis circuit. Afterwards, I would decide where to attend art school. It was amazing playing tennis across Europe, usually making more than enough prize money to cover all expenses. I couldn't wait to visit museums and archaeological sites, and enjoy each country's cuisine. I felt free, with a wide-open future of unknown possibilities.

11 Screen shot from the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

My uncle John Snoddy, also who I never met, was part of the Special Engineer Detachment at Los Alamos, NM, one of the many people that worked on creating the atom bomb. After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, John felt tremendous guilt, as told to me by my grandmother. I doubt guilt is a strong enough word for the role he played, no matter how small, in the murder of a quarter of a million people. How can he and others not own their roles sharing knowledge that could be, was used for creating weapons of mass destruction? I think the buck stops with them.

Creating art was different, and there was relief for me when I realized that art—at least the kind I was aiming for—was a positive with zero negatives. I could aggressively pursue it as ruthlessly as I wanted, and it would never hurt people; rather, it could only do exponentially good things.

Land of Rembrandt

The European tennis tour was a bit of a blur. I remember winning a 21-and-under and getting to the quarterfinals in the open in Birmingham, England. Crossing paths with my sister, Janet, at Wimbledon, I was not world-ranked, so our request to play mixed doubles was rejected. I remember visiting medieval churches and ancient burial grounds in the southwest of England. I did respectably well in some small tournaments in France, the first time having the famous French fish soup, Bouillabaisse, home-cooked by a couple that housed me at one of the tournaments. And playing in Hamburg, Germany. The highlight of the trip was playing in Holland. I got to the quarterfinals at the Metselaars Tennis Club in The Hague before losing to world-class player Kevin Curren.

It got dark late in the summers in Holland, around 11 pm. After the matches and showering, the players and locals hung out in the clubhouse. The barbecue, salads, Dutch beer, and roaring fire made for an awesome atmosphere.

After performing well at the tournament, one of the players, Marian Laudin, a Czech who escaped communism to live in Holland, asked me if I might be interested in playing for the Metselaars club next spring. For me, it doubled as an invitation to live and study in the land of Rembrandt. This was one of those serendipitous moments that changes the specifics in one’s life. I could continue art anywhere, but I didn’t plan on it being in Holland. The Metselaars would pay me $8,000 to play for eight Sundays the following spring, and I could teach tennis at the club making $50 an hour. At the time, the American federal minimum wage was $2.30.

I initially rented a room in a house, then rented a small two-story fisherman’s house, vissers huis, that butted up against the North Sea dunes in Scheveningen, the beach area of The Hague. The house had a large room downstairs that served as my studio.

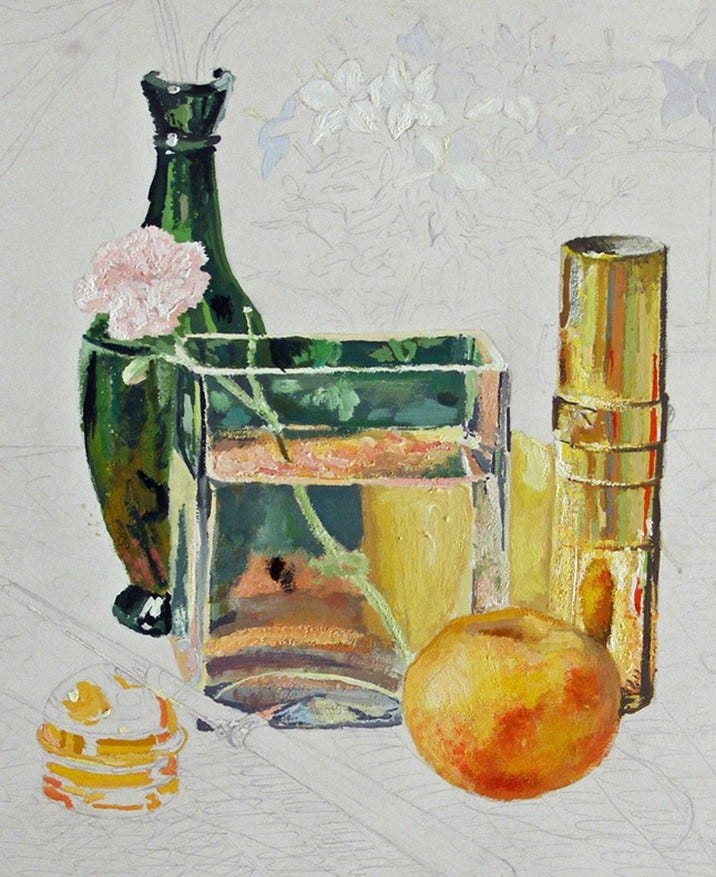

I applied to and was accepted by the Royal Academy of Art. My portfolio consisted of several drawings, my self-portrait, and an unfinished still-life.

12 Still Life with a Pink Carnation, 1977, gouache on paper. The Hague, Holland.

In the still-life, you can see that I was already a pretty good draftsman, a skill simply learned by closely observing reality. It also exhibits the hallmarks of my later years: I love to paint glass, reflections, forms, light, and shadows. Later, I observed that innate talent often involves an instinct to make forms feel round and three-dimensional. Notice the gold cylinder—it feels naturally round, as does the peach and the dark green bottle.

The Royal Academy didn’t work for me; they wanted me to follow their prescribed course and lessons to the “T.” A teacher I disliked flunked me. I recall he lambasted me for doing a drawing in sepia ink, never criticizing the aesthetics of the drawing. The scorn I felt for him must have been pronounced on my face. I quit the Royal and found an incredible alternative that could not have been more perfect for my aims and character: the Free Academy Psychopolis.

My fisherman’s house was literally the last stop of Tram 11, delivering me to my front door. It also went within a block of the Free Academy. What made the Academy perfect for me was that it offered life drawing, drawing the nude, six days a week, nine hours a day (three sessions of three hours each). And it had no instruction, just a monitor to ensure everything went well, like timing the models’ poses. Before 1977 was over, I began a massive immersion into figurative art.

While studying there from ‘77-’79, I created well over 4,000 quick 5-minute drawings, as well as longer poses with pastel and mixed media. I also delved into sculpture and lithography. I went religiously six days a week to school; the exception was when I taught and practiced tennis, which was only a few hours a week. Additionally, I worked on big paintings in my home studio.

On Wednesdays, the full nine hours of life drawing consisted of 5-minute poses. The room was very large, with high ceilings and a northern-facing wall of windows, providing optimal lighting conditions. I would draw as fast as my hand could move, with no hesitation, just a continuous "GO!" and I would squint intensely. Squinting essentializes the light and shadow, revealing very nuanced tones. You don’t see details; instead, the human form emerges from the subtleties of shadows and light.

Late in the evening after the Wednesday sessions, I would tape all 70-85 drawings on my studio’s large wall and take in all the drawings in a glance. I would find repeated patterns in both successful and unsuccessful elements in the drawings. For instance, I would notice if I was making the feet too big or the heads too small. Then the following week, I would automatically make the feet smaller and heads bigger. It's akin to a tennis technique: if you miss by a foot to the right, the next time you aim not at the target but a foot to the left of the target. This process recalibrates your hand-eye coordination to such a fine degree that when you set your sights, you hit it exactly.

The Free Academy Psychopolis, 4,000+ Drawings

13 Woman with Legs Crossed, 1977, Conte.

14 Woman Sitting, 1977, Conte.

Here are three 5-minute Conte sketches, from the thousands I drew. In that short time, I was fairly accurately eye-balling proportions, blocking out shadows, varying line quality based on how sharp the edges were in reality, and a feeling of spatial movement.

One of the greatest consequences of working with perception of reality as my primary teacher was that I developed my own unique style. I like to say that art-making is between me and God.

15 Man Sitting Back, 1977, Conte.

Squinting

Another early technique I luckily used was to squint at both the model and the drawing. This gives the artist a huge amount of tonal information that is obvious when squinting and nearly impossible to judge with eyes wide open. For instance, his left shoulder on the right has only the slightest hint of a contour line, while his left calf and right armpit have more harsh markings, hinting at light, atmosphere, and spatial depth.

Time Effects Style

Other than Wednesdays, the classes had poses that progressed from 1-minute warm-ups to 5, 10, 15, and 25 minutes, then ending with a 1 ½ hour pose, which seemed like a huge amount of time to work. There were also days of only one 3-hour pose.

On 3-hour pose days, I would bring acrylic paints, brushes, water, paper or board, and attempt to paint a complete painting. Not just the figure, but the whole thing—the big picture. By that, I mean the composition, the balance of all the shapes including the back wall, chair, fabric, shadows, blocks of light, etc.

One of my 3-hour paintings is Woman with Her Hands Folded in Her Lap. The size of the board was 36x24”, with acrylic painting supplies. Alongside 20 other artists, it was a performance-like exercise. I have always disliked paintings that combine bold, loose strokes with tight details, like a few of Pierre-Auguste Renoir's paintings, where the face is more in focus. I always felt that a painting should be consistent throughout; either gestural or realistic. Obviously, here I chose a loose approach for the whole work.

There is also the equation that details = time. Details take an abundance of time. So the time factor is a very real part of creating a work, and it affects the style of the work. If she were posing for 30 hours, I could have continued to refine every element, going from the big gesture to a more realistically detailed work.

16 Woman With Her Hands Folded in Her Lap, 1978, acrylic on hard board, 36x24”. 3 hours.

17 Man Sitting, 1977, Conte on newsprint. 1 minute.

A fascinating 1-minute drawing is the one where I blocked out the shadows. It was an excellent exercise in isolating all the shadows into a whole, yet capturing a tonal range. The flexibility in making hundreds of throwaway minute drawings was that I could focus on one or two things, like the abstract shape of a man’s shadows or the spatial relationships. You can feel his head tilted forward from his shoulder, his right knee closer to us, and his left knee is closer still. Being able to solve these kinds of problems in a minute gave me confirmation that I had the talent for art and that I should keep driving it.

$150 a Minute

Two dear friends and collectors, Bonnie and Robin Priest, are both in the European financial world, and I would visit them in London once or twice a year, taking a portfolio of some works I thought they might like. They bought the drawing of Crouching Man for $150, and they found it highly amusing that I could make $150 a minute.

18 Crouching Man, 1977, Conte.

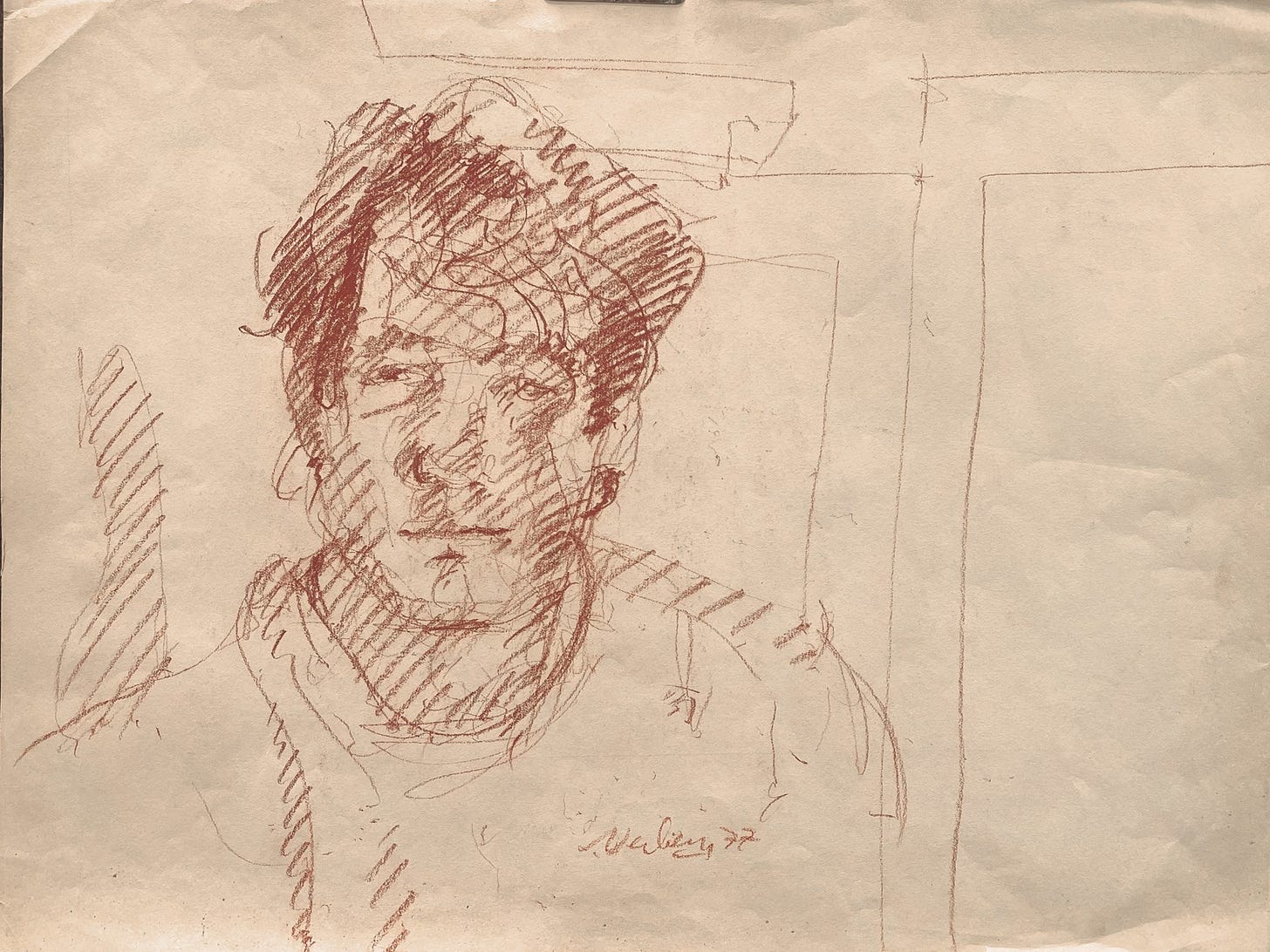

19 Self-Portrait, 1977, conte on newsprint, Hamburg, Germany.

Grappling with the Future

The Self Portrait drawing from the summer of 1977 was done in Hamburg, Germany, during a week between tournaments. I spent a profoundly moody time reflecting on taking the scary step of being an artist. Though I had made a commitment, I was still testing if I had what it took. I paused and reflected a few times over the next few years, asking if indeed I was making the right decision. It would have been horrible if I turned out not to have the artistic talent I hoped for, while also not realizing my potential for a world-class tennis career.

I would be playing tennis for the Metselaars in the spring for the next few years. The money from it was what I would live on, but on this day, I decided not to go on tour. Instead, I would take 9 months out of each year to give art everything I had. Ultimately, that choice would unlock my potential and prove to be a good move.

21 Claudette, 1978, graphite on paper.

Art Outside of School

Aside from attending life drawing full time and teaching just enough tennis to make ends meet, I also did drawings and paintings of friends. An example of one of the sketches of Claudette. As you can tell from the drawing’s "echoes," she was moving around shifting her arms and legs. I find it interesting that in drawing there are often layers of different poses, "echoes," that have a fresh quality to them, similar to the Chauvet Cave’s Horse Heads from 30,000 years ago.

Metaphors and Life-sized Paintings

These three life-size paintings were created from reference drawings, much like the earlier Conte drawings, 5-minute ones. There wasn't enough information in the drawings to do realistic works, so I didn't try. I kept them as semi-abstracted figures and settings. I retained the transparent quality from the drawings. It was also something that I saw Picasso do, and I liked how it created a winking physical feeling in my eye. Having figures transparent is also an interesting psychological metaphor.

I was also trying to create as much depth as possible. With the idea of the psycho-symbolism of depth of character.

Treating Linen and Color

I had to learn technical art knowledge from old books or ancient sources like Vasari’s Lives of the Artists. One disgusting technique was to warm up dried rabbit skin with water in a saucepan that was placed in another pan of boiling water, bain-marie (the same technique to melt chocolate on the stovetop). It makes a foul-smelling warm gel that you slather on raw linen; it acts as a protective barrier, as oil paint will rot untreated linen or cotton. I liked how it left the linen its natural color, but modern-day gesso is much better for the health and longevity of the linen canvas.

My use of color for the following three paintings came about by my emotional and sensual response to people and to visual stimuli. Scarlets and sizzling greens could be used as a color scheme in response to an extroverted model, giving the painting a sultry electric atmosphere. The colors should simulate the light vibrations from nature; in effect, the nuances of the color should excite and "tickle" the eye, be edible, and leave the spirit intoxicated!

The Friends that Posed

Drawing and painting friends make the subject matter more personal. Life drawing poses for class are wonderful to learn how the body looks from countless angles, but they are impersonal. Having friends model for me is a personal bond, which subliminally finds its way into aesthetic choices. When a friend poses, I can feel if the artwork is progressing true to how I view them. This makes me stop and regroup, or triggers a green light. These green lights then lead to color choices, to how to place the hands, fingers, and the tilt of the head. This was an important shift from being a life drawing student to being an artist.

Jette van der Meij was a music student in Amsterdam while I was in art school. Aside from posing for Jette, she also posed for my realistic painting Woman in Blue. After her education, she went on to be a well-known Dutch singer and actress. The linen canvas was one of those treated with rabbit skin glue. I purposely left some of the surface linen exposed when it had the right tone. You can see it as the beige stripe of the wall, part of her forearm, a little on her hip, and as part of her calf.

I first met Rob Mechielsen when he was posing at the Free Academy Psychopolis, and he was also a student there. He posed for this painting, Rob II, Man’s Head, and Portrait of Rob. He went on to become a well-known international architectural designer, using innovative means and materials, and creating heightened emotions through his use of form, space, and environment.

22 Jette, 1977, oil on linen, 52x42".

23 Rob, 1977, oil on linen, 48x40".

24 Rob II, 1978, oil on linen, 30x50”.

These three paintings wrapped up my art student education. I would still be learning with every work I made, but the time came for me to move beyond being a life drawing student and fully invest in creating artistically meaningful works. In 1979, at the De Sluis Art Gallery, in a historical building on the side of a canal in Leidsendm, Holland, I had my first major solo show. At age 22, I was closing out my self-guided art education and embarking on an artist’s career.

Next the stage I would be transatlantic commuter dividing my time between New York City and The Hauge.

This chapter was incredible and so powerful. Wow! I am in awe. How wonderful that school sounds, and how sternly you took yourself by the “horns” and focused your creative energy. All the art in here is beautiful, but my favorite is Jette with the raw linen canvas in blue and gold. Thank you so very much for sharing your story.

Love seeing your early art…that first self-portrait and the still-life are faves already! ✨🥂✨