Chapter 19, Dynamic Spaces: Two- and Three-Point Perspective

From my upcoming new edition of The Art Studio Companion

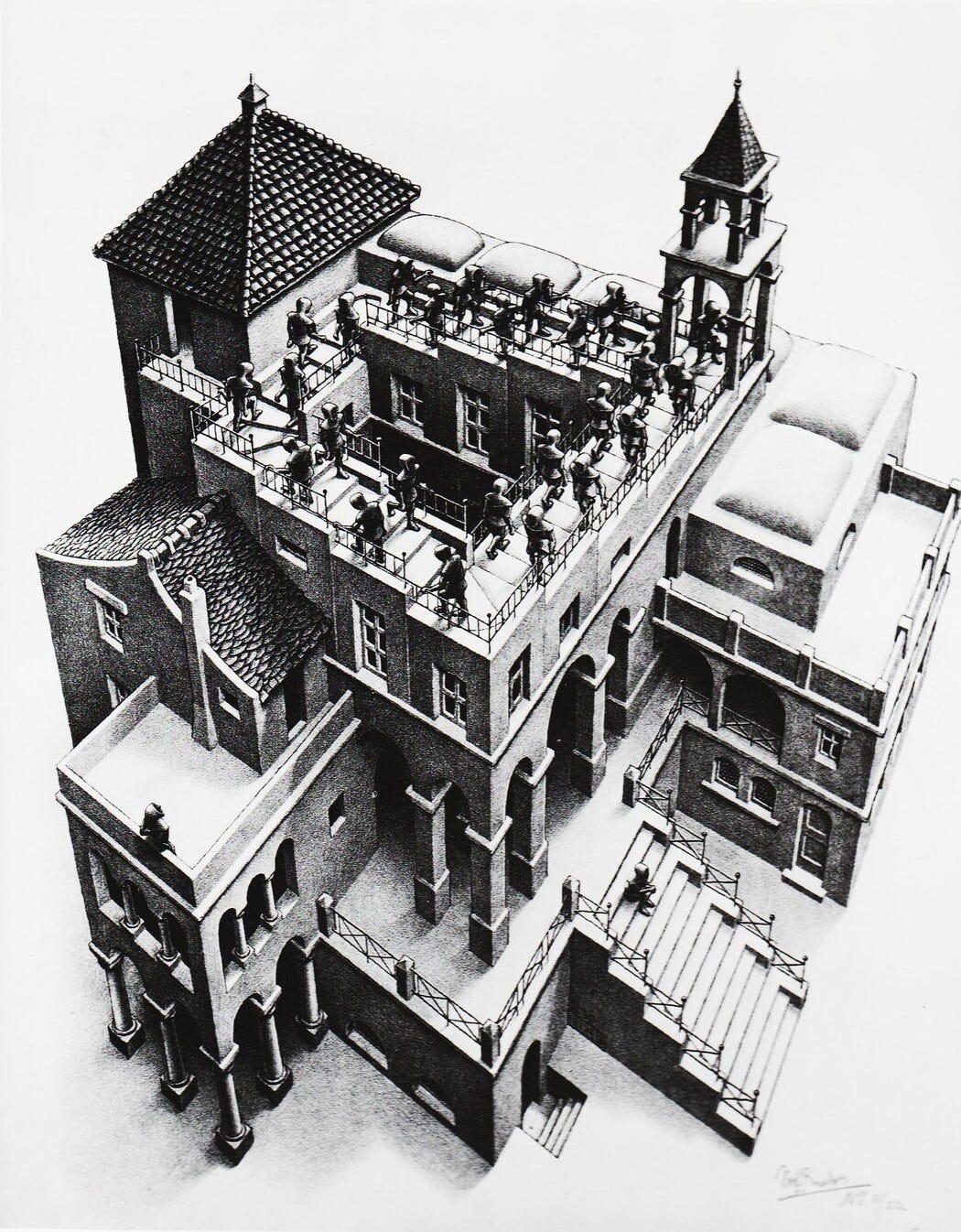

145 Maurits Cornelis Escher, Ascent and Descent, 1960. www.arthive.com.

In this study, we examine two- and three-point perspective, which are commonly used to draw the interior and exterior of box-like structures from angled views. They differ from one-point perspective, which involves looking at a structure or interior straight on.

Two-point perspective: Looking at a structure or interior from an angled view (oblique).

Three-point perspective: Looking at a structure or interior from a diagonal view.

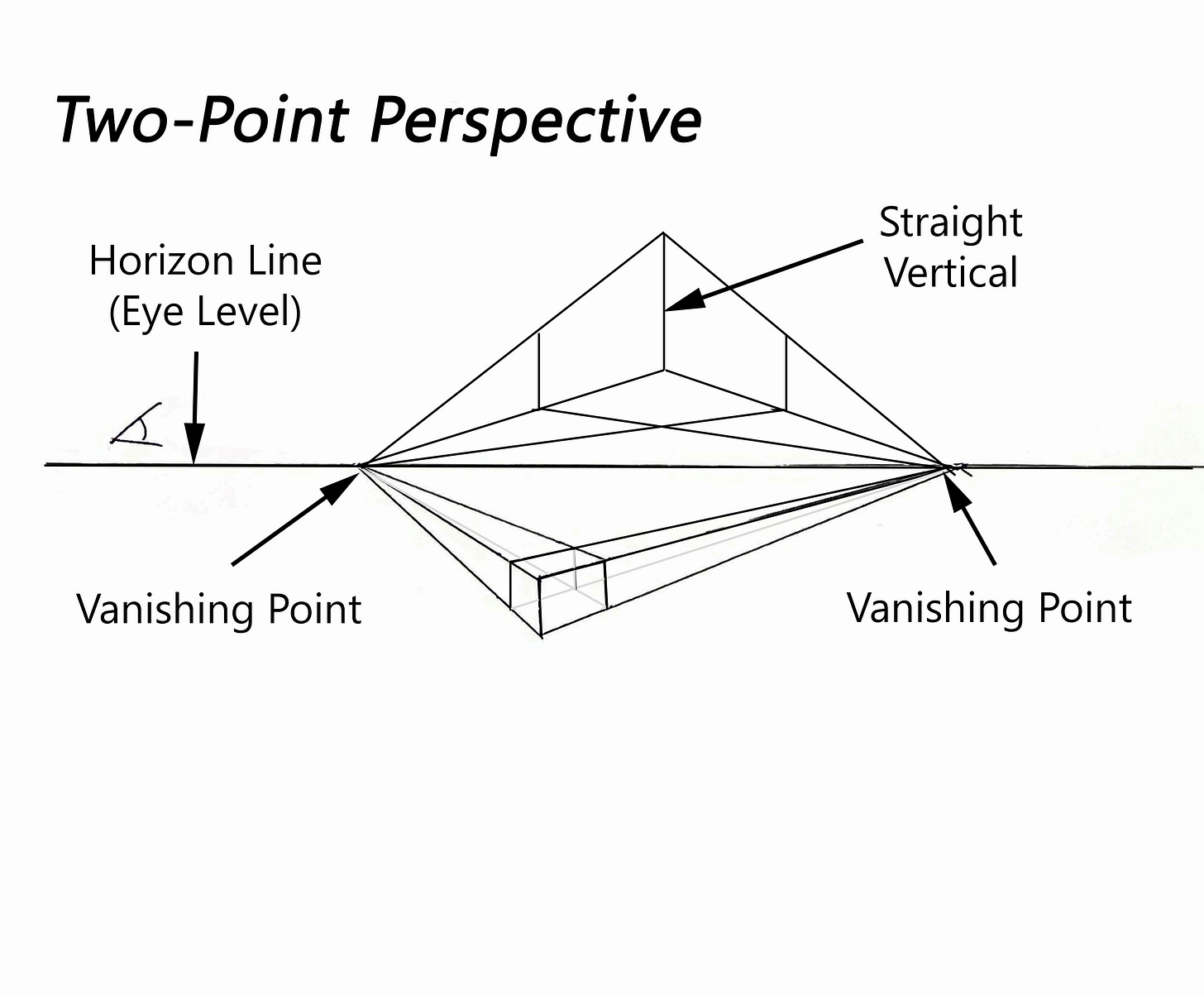

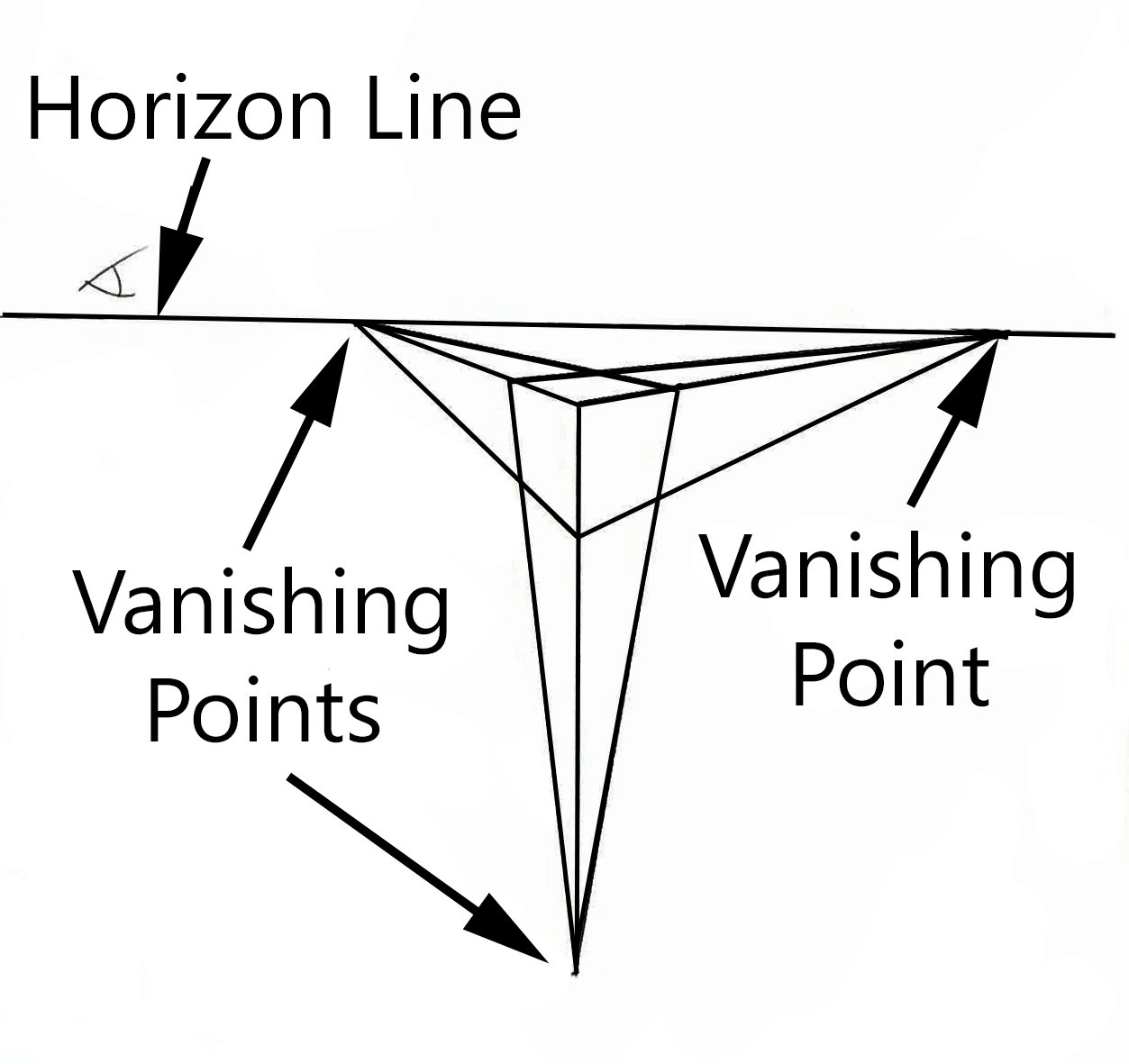

146 Newberry. Demo of two-point perspective.

Practice #1

As always, it is crucial to reinforce your understanding through practice. It is fun to explore the theory presented in demos 146 and 147. Draw the following on paper with a pencil or pen:

Draw a horizon line; this is also known as eye-level.

Mark two vanishing points on the horizon line.

Draw the vertical lines of the structure; these will be the corners of the structure.

Draw diagonal lines from the top and bottom of each vertical line (corners of the structure) to the vanishing point on the opposite side. These will serve as the edges of the structure’s sides.

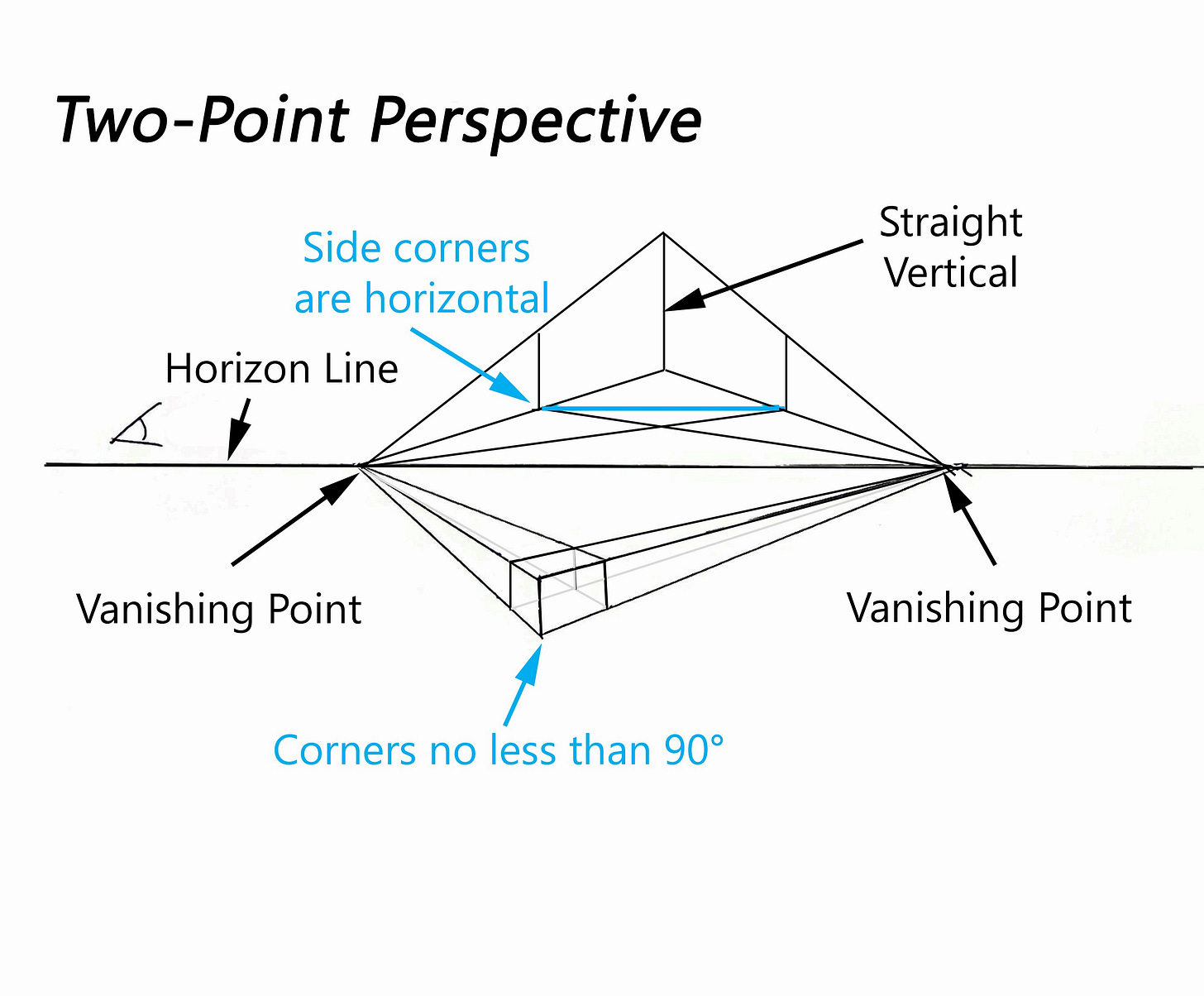

It takes a bit of practice. I suggest drawing as many structures (boxes) as you can fit on one page. Draw some boxes above, below, and traversing the eye level. The angle of the corner of the room or building should not be less than 90 degrees.

There is one qualifier: If you draw a box either too high above or below eye-level, the 'V' angle of the corner will become very narrow, less than 90 degrees. It looks very dramatic, but it is not realistic; it would mean seeing the object both in front and behind you at the same time. (Kind of like the space-time paradox, for us Star Trek fans.)

147 Newberry. Demo of two-point perspective with notes.

Two-Point Perspective in Denouement

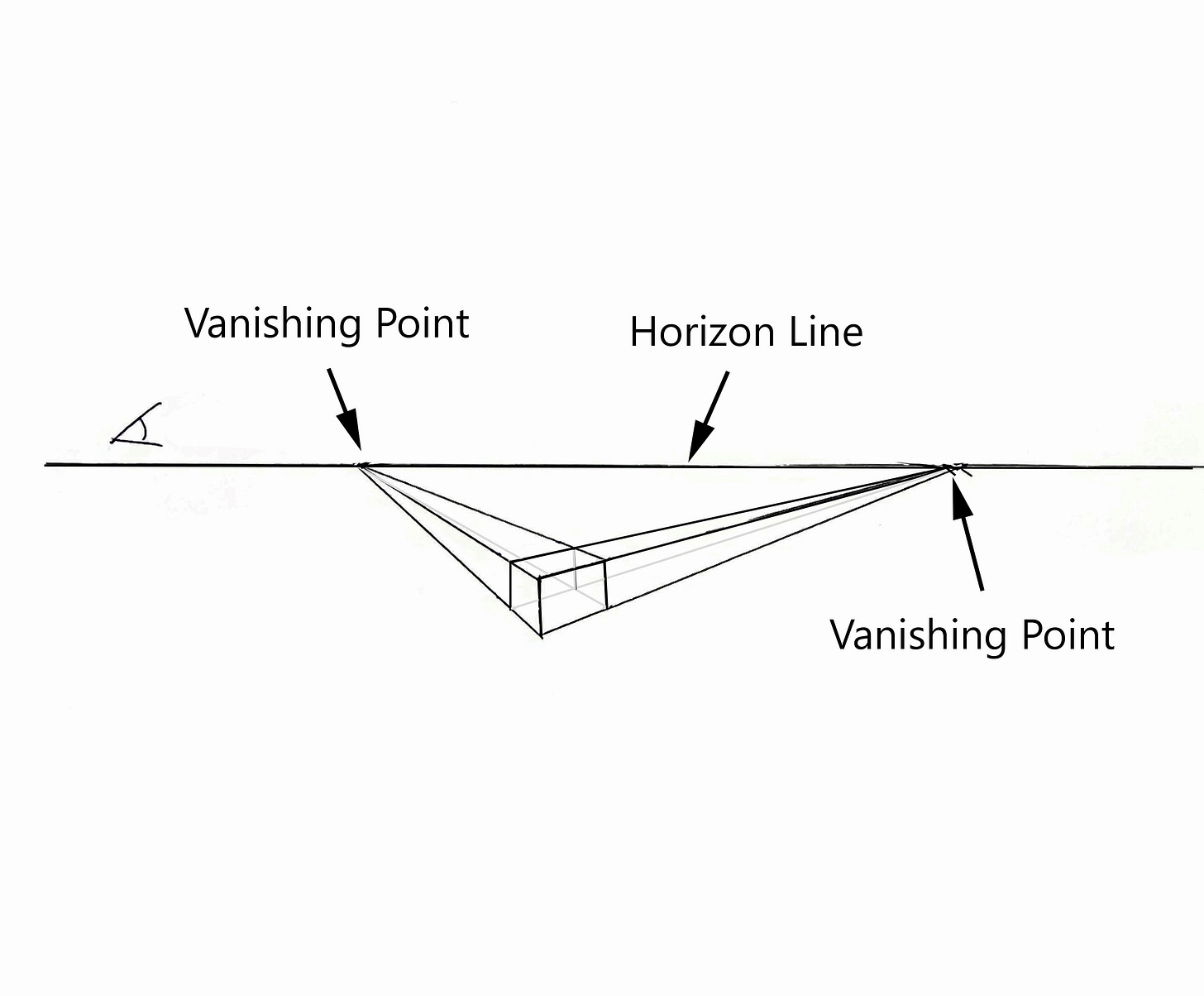

148 Newberry. Demo of two-point perspective below eye-level.

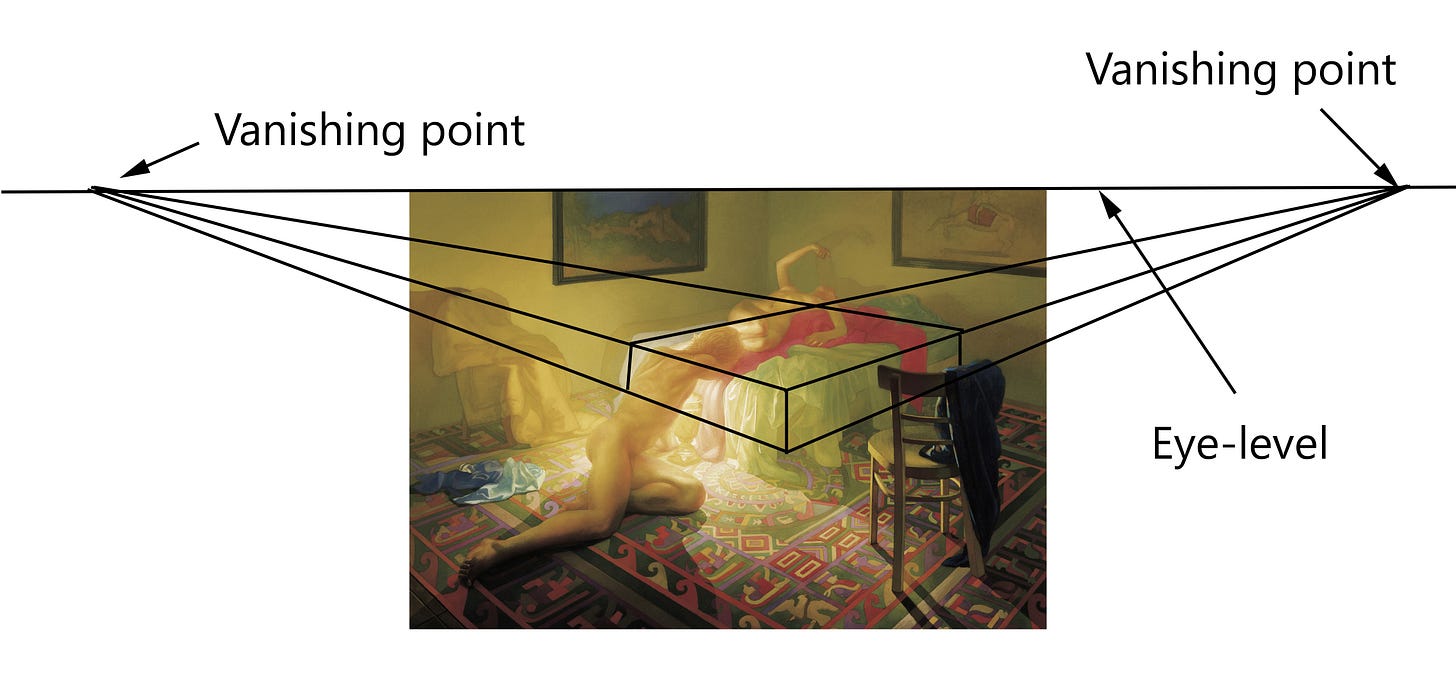

The above diagram shows the theory, and below you can see how the two-perspective works in my painting Denouement.

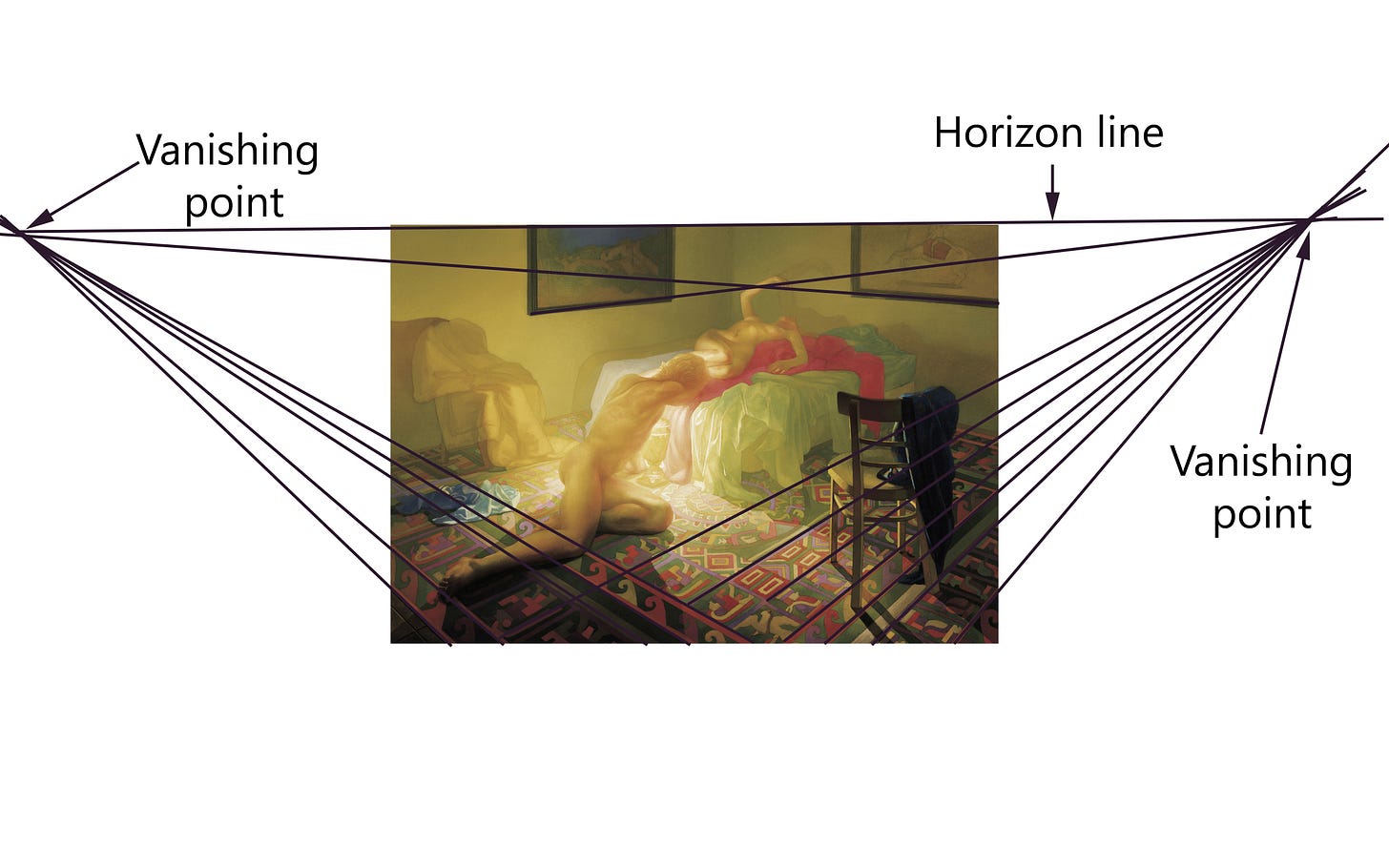

149 Newberry, Denouement. With my markup.

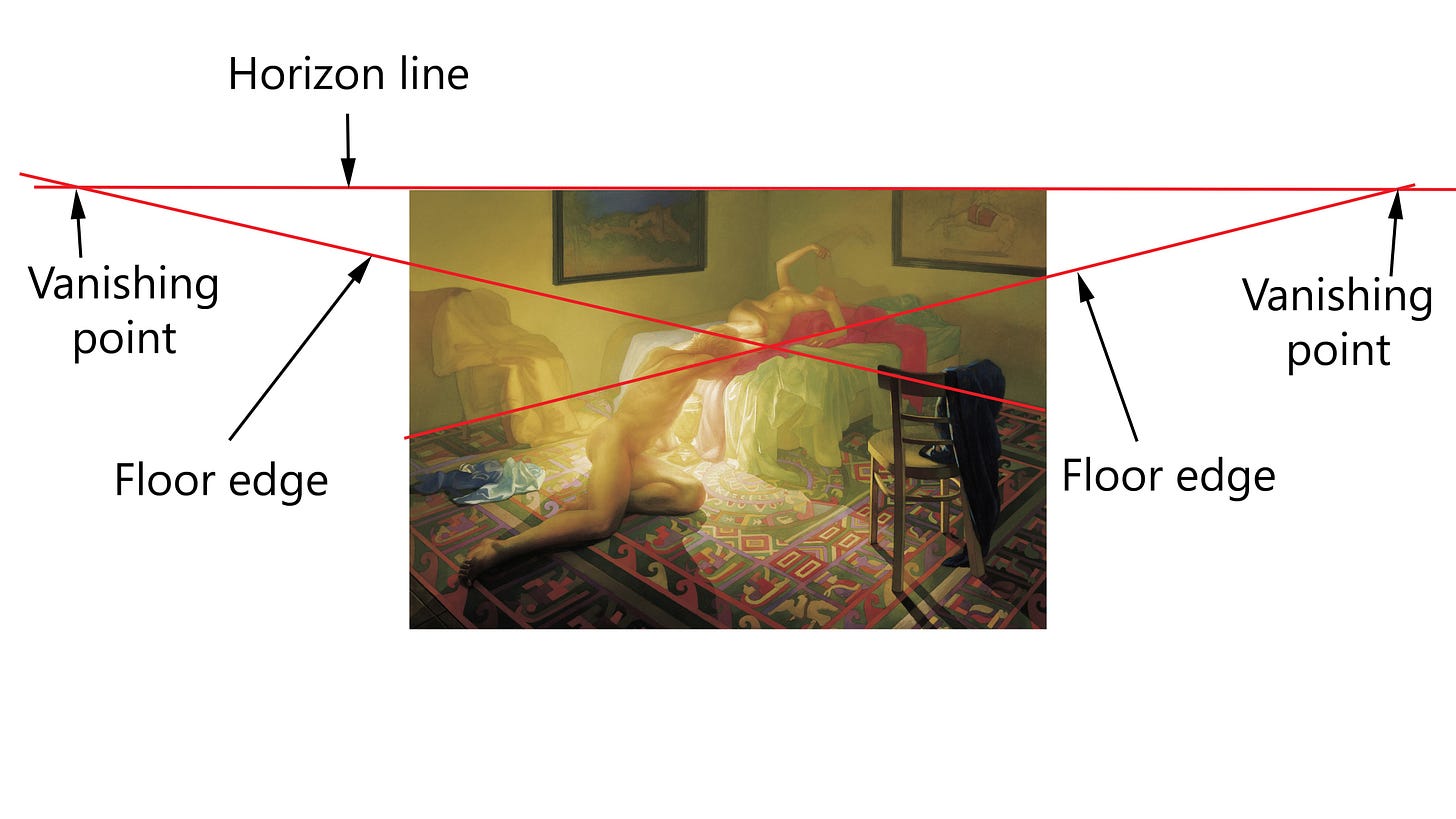

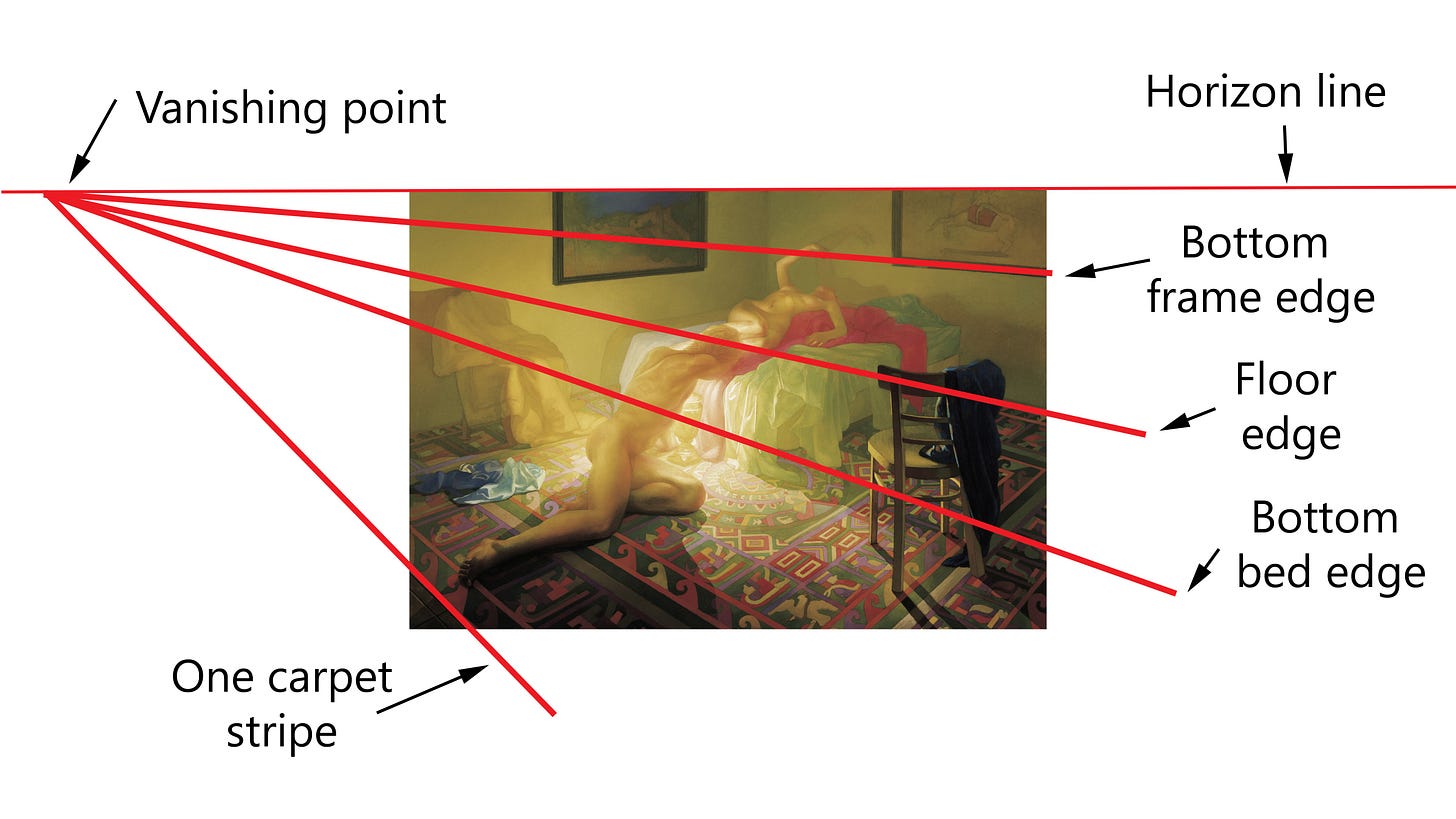

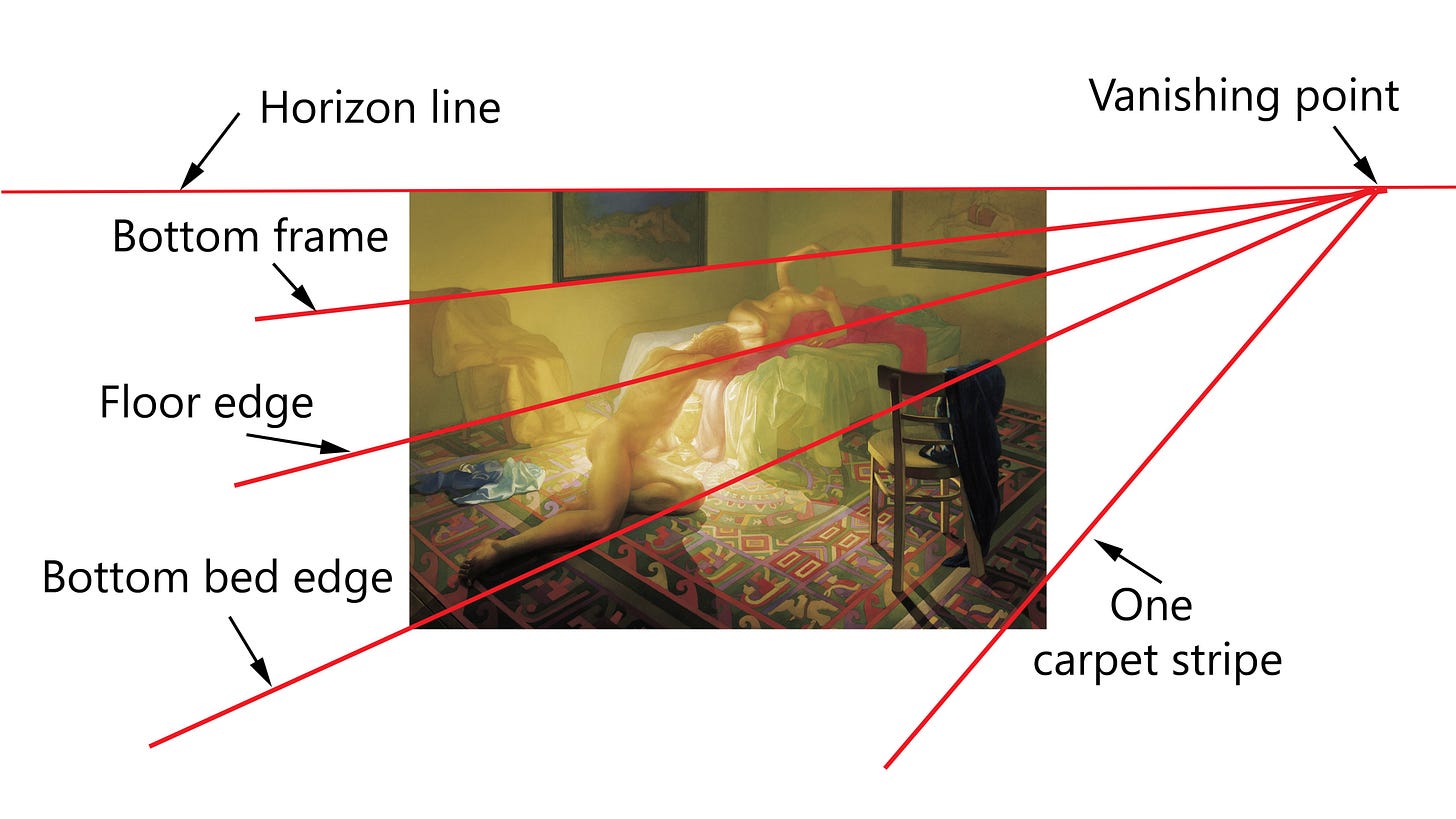

In the painting, my eye-level was just above the scene, so I was looking downwards at everything. In real life, the carpet, bed, and room were all symmetrical and parallel. The floor’s edges were parallel to the bed’s edges, as were the bottom edges of the framed artworks in the painting and the stripes of the carpet. In its study, I drew them by sight to start with. Then I got a bigger sheet of paper so that I could draw the extended horizon line and vanishing points way off to either side.

150 Newberry. With my markup. Floor edge.

151 Newberry. With my markup. Left vanishing point.

The bed’s edges, the carpet’s stripes, the floor’s edges, and the bottoms of the frames all share one of the two vanishing points.

152 Newberry. With my markup. Right vanishing point.

153 Newberry. With my markup. Vanishing points of the carpet lines.

Mastering two-point perspective will give you great confidence in depicting structures in your artworks.

Three-Point Perspective

154 Newberry. Three-Point Perspective.

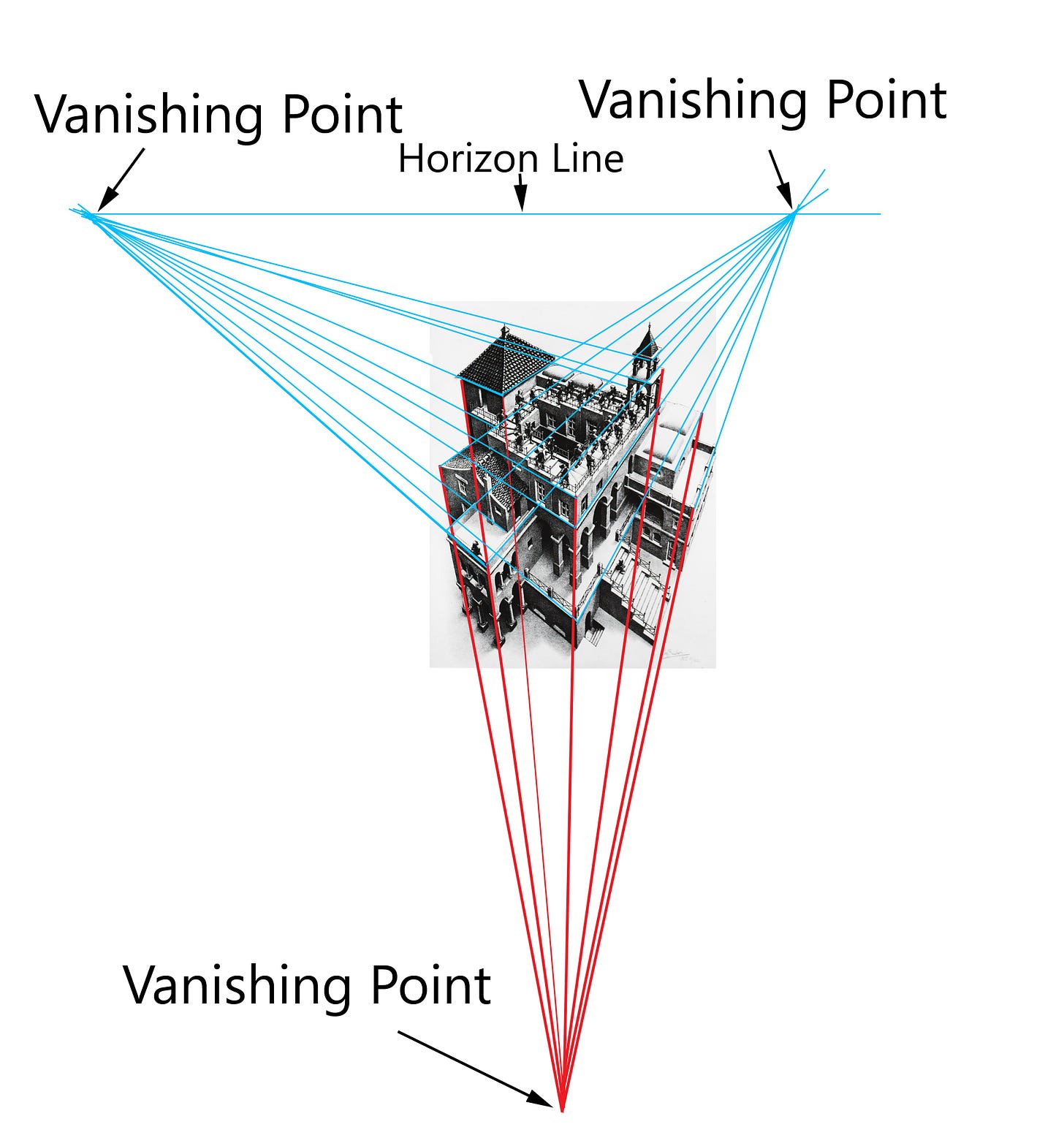

Three-point perspective is similar to two-point perspective, as both have two vanishing points on the horizon line and work the same way. The difference is that three-point perspective has a third vanishing point, which is either above or below the horizon line. This third vanishing point is used to create the illusion of height and depth in the artwork. Three-point perspective is often used in drawings and paintings of tall buildings, skyscrapers, and other objects with a strong vertical component. Essentially, it gives you a bird's-eye view from above or a dog's-eye view looking up.

In three-point perspective, the third vanishing point pulls all the verticals together at the vanishing point. In reality, we see three-point perspective more often than we realize, such as when seeing tall buildings or looking down at our stoves. The top of the stove's surface will be broader than its base, which is further away from our eye level. M. C. Escher's wonderful etching of a palace is a perfect example of three-point perspective. It's easier to see with the help of a diagram and my markup showing how the vanishing points line up.

155 Escher. With my markup. Three-point perspective.

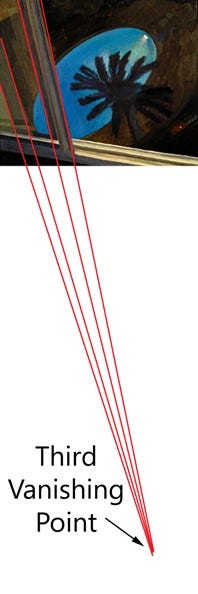

156 Newberry, Pool at Night, 1993.

To conclude, here is one of my paintings, Pool at Night, which prominently features three-point perspective. Notice the side of the windowsill and how it veers left at the top. My closeness to it created a dramatic effect. By following the vertical lines of the window down, we discover they converge at the third vanishing point far below us. Although three-point perspective is complex and requires practice in theory and observation, just remember that it's like looking at a stairway to heaven: ultimately, somewhere way off the page, parallel lines will meet.

157 Newberry. Pool at Night. With my markup.

Practice #2

As always, it is crucial to reinforce your understanding through practice. Like in Practice #1 draw it in theory, this time using demo 154. Draw a horizontal eye-level line, mark two vanishing points on that line, and mark a third vanishing point above or below. Then use these points to create boxes on your page.

Practice #3

As always, it is crucial to reinforce your understanding through practice. The lesson here is to merge real life perception with the three-point perspective theory. Draw a box-like structure from real life, like a gift box, from a dramatic angle. Do your best to tweak the theory of the three vanishing points with how the box looks like in real life.

When practicing three-point perspective, I recommend using a large sheet of paper so that there is plenty of room to include the three vanishing points. In fine art, I never recommend using a ruler, as paintings and drawings should show a relaxed and confident freehand. But for drawing the vanishing points, I make an exception and recommend using a ruler to line everything up.

It is worthwhile and a tremendous feeling of satisfaction when you connect the theory to real life.

One more word of advice: It is an inconvenient truth that artists who attempt to draw structures without understanding perspective theory usually end in failure, with results that look extremely childish or incompetent. Being able to execute the perspective of box-like structures will elevate the artists to a high standard of professionalism, make their drawings/paintings look natural, and give them tremendous confidence and freedom in their art making.

Oooh it is as if I’ve gone back in time with my Mama explaining vanishing points. Love this clear explanation Michael, a ‘must read again’! 💙💫

Michael you are just as amazing as a teacher as you are an artist! I’m going to take the time and do this later this weekend when I have a moment to myself. Sending you love! 🥰