Chapter 14, Learn from Art History: Shedding Light on Light

From my upcoming new edition of The Art Studio Companion

105 Raphael, Deliverance of Saint Peter, 1514. WC.

In this study, we analyze the evolution of light in painting, its interaction with form, depth, and color, and its role in conveying narrative and emotion.

From the flicker of a candle to the glow of the sun, painters have been capturing the play of light for centuries. Light is the zenith of painting and it was the catalyst to key artistic movements throughout history, such as the Golden Age of Holland, the Italian Renaissance, and French Impressionism. Light can transform a simple scene into a masterpiece, illuminating the beauty of nature, revealing the depth of emotion, and adding drama to the mundane. In this chapter, we'll delve into the techniques, styles, and innovations of the great masters.

Light in a painting is intricately tied to form, shadow, and depth.

Let’s start with the Horse Heads depicted in the Chauvet Caves of France.[1] Dating back 30,000 years, the artist shows a judicious use of light, shadow, and depth bringing the horses to life. Notice the striking darkly shadowed detailed muzzle of the closest horse and contrast against the light cave wall, popping it forward, while the muzzle of the distant 4th horse is faded in atmosphere.

106 Horse Heads, Chauvet Caves, 30,000 B.C. WC. Previously shown.

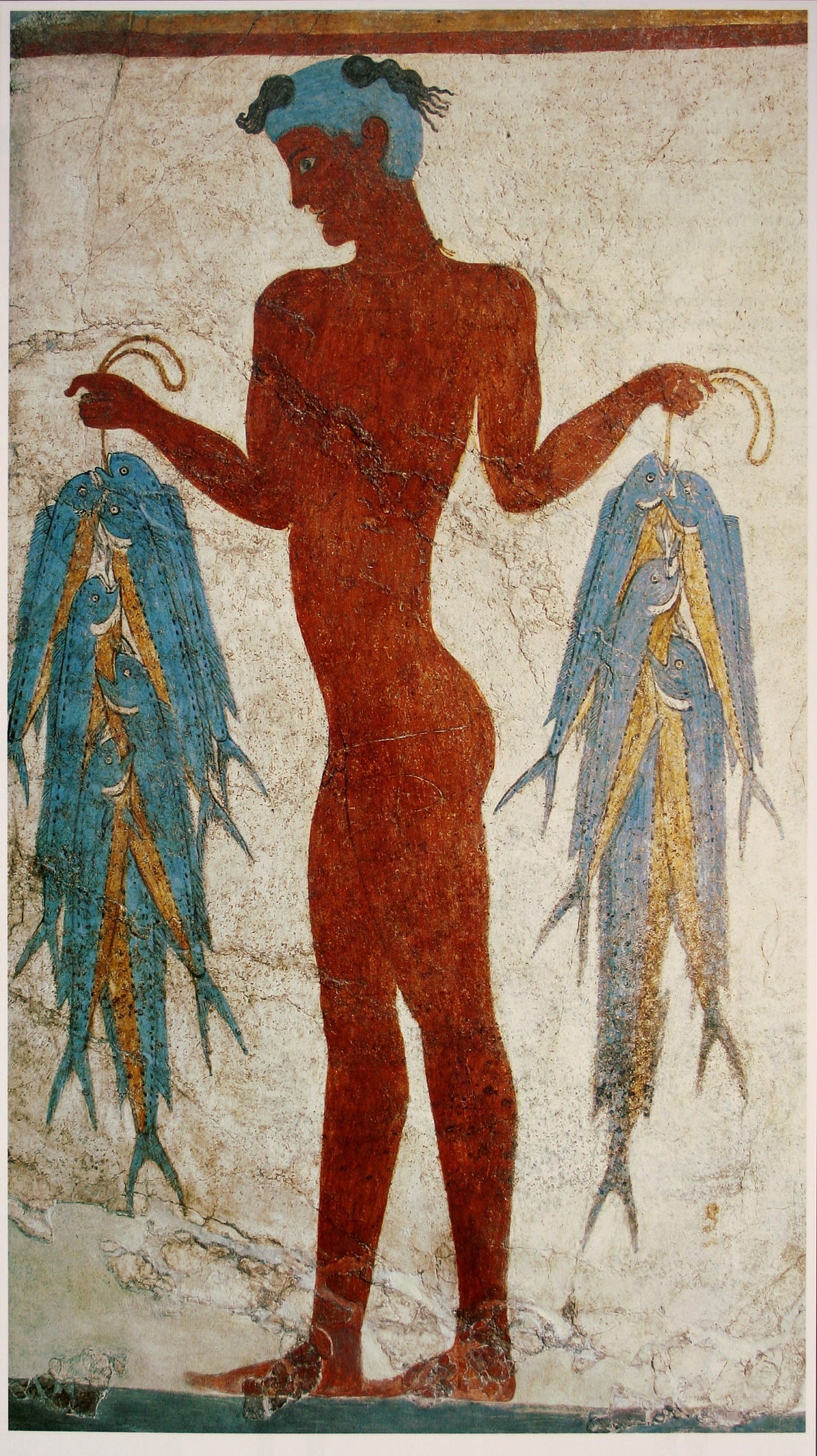

In contrast to the Horse Heads, this image of a Minoan Fisherman, 1650-1500 B.C., doesn’t have light on the male body or on the fish. He his darkly silhouetted against the pale white background, beautifully proportioned, but because there is no form and no depth, there is no light—showing us a flat graphic design, in essence a decoration.

107 Fisherman from Akrotiri-Santorini, 1650-1500 B.C. Fresco. WC.

There are a few examples of ancient Greek painting. In the Pompeii frescoes in Italy, we get some idea of what might have been classical Greek painting. In Europa and the Bull, notice the shadows: her face has shadows over her eyes, on the side of her nose, and rounding her cheek; she also has shadows on her neck, right upper arm, in her lap, and along her right leg; the bull has a pronounced cast shadow on the ground; notice the fadedness of his left back leg; and the fully shadowed forequarters and head. Notice how the rock ledges are also consistently shadowed, with the shadows of the bull and Europa on their left sides. All these shadows set the stage for some brilliant lighting effects. A strong light consistently comes from the upper right side, with bright highlights on Europa's breast and ribcage, the bull’s muzzle, and the rock faces.

There is an interesting paradox: the more light on subjects, the less good they are as decoration, and with light, they become more a vehicle for contemplation.

108 Europa and the Bull, 1st C. AD, Pompeii. WC.

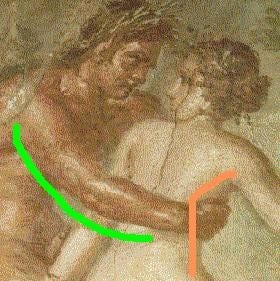

109 Lovers, 1st century AD. Pompeii. WC.

110 Lovers. With my markup.

The Lovers is a great example of the artist using light to bring out the form of anatomy. Notice the flicks of highlight along the man's arm and the flow of light along the woman's torso.

111 Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on oak panel. WC.

The Northern Renaissance artists' works are noted for attention to extravagant details. In Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait, notice the tour de force of exquisite details. Though this painting has all the ingredients of light, shadow, form, and depth, there is a puzzling lack of the feeling of light in the painting overall. His raised right hand suggests the main source of light is coming from our left, but notice their clasped hands are lit, but logically they would be in cast shadow. His massive hat would logically cast more shadow on his face. So there is another element to creating light, and that is that the light must be consistent. Van Eyck probably painted many elements of the painting separately at different times of the day, hoping they would all sync; alas, it doesn’t all mesh in regards to light.

In this da Vinci, we have one light source, unlike the van Eyck work above. There is an important, though subtle, difference in developing light in painting. Notice the woman's shoulders. Van Eyck used just enough light to give shape to the green cloth and white scarf. In contrast to that, da Vinci cloaked a sheen of light over both her flesh and cloth of her shoulder. The light and shadow on her face match perfectly with the ermine’s. We have the sense that a single light source is consistently lighting her head, hair, left shoulder and arm, hand, and the ermine. The painting also has strong spatial placements; the ermine’s head is closest to us followed by her hand, face, her left shoulder, and furthest back her right elbow and shoulder.

112 Da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine, 1482-5. WC.

113 Raphael, Deliverance of Saint Peter, 1514. WC.

Raphael makes a great breakthrough with the light in The Deliverance of St. Peter. He takes the idea of the halo, yet he wants to make it feel real. Behind the angel is glowing light, as if the light was coming from the end of a tunnel. An interesting phenomenon is the transparency of the angel and its wingtips. Thought she is silhouetted by the light; she is painted much lighter than the two guards and prisoner. A key feature of this transparency is that her wings are much darker beyond the white light. And notice how her right arm dissipates into the light.

114 Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, 1610. WC.

Caravaggio went after dramatic light with passion. He intensely contrasted light and dark. It is reminiscent of melodramatic black/white photography, undoubtedly, he would have been familiar with the camera obscura.[2]

115 Rembrandt, The Night Watch, 1642. WC.

On the other side of Europe, Rembrandt, the king of light, achieved the zenith of tonal light unmatched by any other artist before or since. In Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, he spotlighted the people and things in his paintings. He used light to highlight the things he wanted us to focus on. But he also solved the difficult problem of spatial relationships. It is quite simple for us to track the spatial relationships of all the people in his painting; it seems the furthest depth is about 40 feet away, in contrast to about 4 feet of depth in Caravaggio’s David. The significance of spatial depth is that the painted scene feels real—not in detail, but because we can look very far into the canvas. Consequently, when the artist integrates light with the depth, it makes the light feel real and tangible, rather than just a symbol of light.

It is interesting that the lighting setup in The Night Watch is similar to the Van Eyck couple portrait. In both paintings, there are two light sources: one from behind us on the left, and one from further back on the left. The key difference between the two paintings is that Van Eyck used light to heighten all the details, while Rembrandt directed the light, making details subservient to the light.

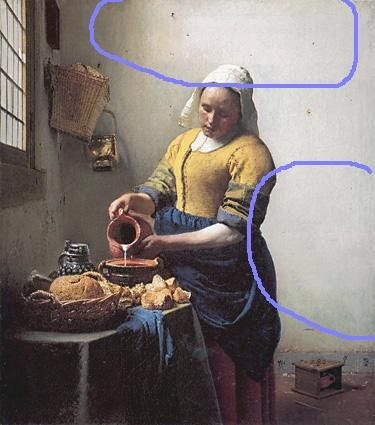

116 Vermeer, The Milkmaid, 1658-61. WC.

117 Vermeer. With my markup.

It is impossible to discuss the topic of light in painting without mentioning Vermeer. Diverging greatly from Rembrandt in style, Vermeer pushed the boundaries of how realistically one could depict the play of light. It can be argued that no other artist, past or present, possesses an eye as attuned to the subtleties of light combined with realism as Vermeer.

Take, for instance, in Vermeer’s The Milkmaid, the area just above her head, where a remarkably delicate lighter tone takes the shape of a rectangular form. Could this be a trace of a previously hung painting, leaving behind a faint "ghost" against the clean wall? Moving our gaze to the lower right, behind the subject's body, we notice a series of progressively subtle shifts in cooler colors, contrasting with the pinkish tint above.

In every area of the painting, we encounter nuanced variations in tone and hue. There is also an ineffable hierarchy to the shifts of light and shadow. Vermeer's ability to recreate the intricate interplay of light situates him at the pinnacle as an artist and visual scientist.

118 Monet, Haystacks, End of Summer, 1891. WC.

An artist who had a tremendous impact on the evolution of light was Claude Monet, a French painter and one of the founders of the Impressionist movement. Monet's exploration of light can be seen in his series of paintings that depict the same subject under different lighting conditions, at various times of day and seasons. One of his most famous series is the Haystacks, where he painted haystacks at different times of the day, studying the subtle changes in color, shadow, and atmosphere caused by the light's conditions. An important innovation is that he took the studio outdoors to carefully recreate sunlit landscapes.

Additionally, Monet experimented with the concept of complementary contrasts of light and shadow, achieving a heightened sense of luminosity and vibrancy in his paintings. In Monet’s Haystacks, End of Summer, the light has a warm-yellow hue, while the shadow and depth have blue hues. But a fascinating and keenly perceptive example is how Monet included bounced light and color from the golden ground and the blue sky.

Notice that the haystack shadowed walls are comparatively warmer, while shadowed parts of the cone-tops are bluer. The walls incorporate the warm ambient bounce of the golden fields, while the cone-top shadows incorporate the cool ambient bounce of the blue sky. These subtle observations are derived from closely observing them in real life on location and at a particular time. Monet undoubtedly kept a tight watch on the time of day for each of his haystack paintings.

Monet's explorations of daylight added a profound layer to humanity's comprehension of color and light theory. His artistic endeavors continue to deepen our appreciation of the interplay between light, color, and our perception, leaving an enduring legacy in our understanding of visual phenomena.

119 Newberry, Denouement, 1987, oil on linen, 54×78”.

One of my lifetime goals, starting out as a young artist in my teens, was to combine the light of Rembrandt, the color light of the French Impressionists, and the romantic humanism of the Renaissance. My attempt to integrate all that I learned from these great artists is my painting, Denouement.

Impressionist color doesn’t integrate easily into classical painting. One way I got around that was I did hundreds of pastel studies—layers of overlapping pure colors—of all the elements in the painting done from real life. Integrating all these elements was a massive three-year-long project, working Monday through Friday on the painting, and working weekends to make ends meet.

I think I succeeded admirably in achieving elements of the feeling of light, imbuing it with color, and celebrating a moment of eudaemonia—matching ends and means.

The depiction of light in painting has evolved over time, from cave painters to Rembrandt's subtle stylization, from Vermeer's realism to Monet’s daylight, and beyond. We have seen how artists have experimented with light to achieve a feeling of brilliance, illuminating the path for future generations of artists and giving future generations of viewers an evolutionary awareness of light.

Practice

As always, it is crucial to reinforce your understanding through practice. I suggest copying one Vermeer and one Monet painting. Use the Vermeer to focus on tonal nuances, light, and shadow, and use the Monet to study the colors of the shadows and lights. You will need an abundance of time; a minimum of 20 hours for each one. Allowing for a lot of time allows you to zen out and simply focus on painting, not the immediate result. Afterwards, you will find that you actually see real-life light and color in an extraordinary way, and, importantly, your painting skills will go up several notches.

[1] Prehistoric cave painters hold a special place in my heart. Their art feels like a direct connection from a real individual, reaching out to me across tens of thousands of years. It is incredibly alive, inspiring, and fills me with pride as an artist, motivating me to carry on the tradition they began.

[2] Da Vinci wrote about the camera obscura in one of his notebooks from 1502.

Thank you for this series Michael. I will be paying more attention to details in paintings going forward.

Your painting is exquisite. I enjoyed examining all the nuances. Thank you so much for sharing. 🙏🕯