2004 A Man with his Art on his Sleeve

Architect Peter Cresswell interviews artist Michael Newberry.

Published in The Free Radical -April-May 2004

Who is Michael Newberry?

Michael Newberry is an artist with a passion. In these days when the word ‘artist’ usually requires the prefix ‘bullshit-’, Newberry instead has a vibrant, shimmering painting style that screams of exuberance and a raw joy in being alive. “Newberry’s paintings are the work of a strikingly original artist,” declares Assoc. Professor Stephen Hicks of Rockford College, Illinois, “Newberry’s work speaks to the senses, the intellect, and the passions of those who do not need the judgment of history to tell them what is great, but who can themselves make the judgment of history today.”

Newberry is not modest about his work - and in truth he has much to be immodest about. He has a manifesto which speaks with the same challenging directness of his paintings - a manifesto that throws out a strong challenge to the artistic apostles of the meaningless and the mediocre:

“To Enlighten, Not to Pitch Obscure Puzzles … To Bless Earth, Not to Damn Existence … To Impart the Breath of Life, Not to Draw Degradation … To Bring Forth Shimmering Passion, Not to Wallow in Despair …This Manifesto is the Signal for a Moral Revolution of Human Values in the Arts.”

Not just combative then, but also distinctly unfashionable. Newberry’s manifesto marks him out not just as an artist who means something, but also as an ‘art-activist’ for whom art has real life-and-death importance – too important for him to leave unchallenged the posturing post-modern mediocrities that have for some decades infested the art world. Which prompts our first question: Michael, do you see yourself as primarily an artist, or an activist?

MN: An artist 100%. Making art and responding to it is my life. Writing and lecturing on aesthetic issues and directing the Foundation for the Advancement of Art are secondary. But all of it comes from the same place: from my love for art.

TFR: Does your activism help your art? Do you begrudge the time away?

MN: Activism doesn’t help my art directly but it does give me an incredible sense of freedom. I love taking the actions necessary to defend and promote the art values I believe in. I am definitely motivated to denounce the recent defacement of the Goya etchings as I am to support a brilliant artist like Stuart Mark Feldman.

TFR: You've just held your first conference for the Foundation for the Advancement of Art in New York. How was it?

MN: Participating in the conference was a blast and the goodwill was fantastic. I think that there are a few points that everyone came away with. From philosopher Stephen Hicks, that postmodernism is a nihilistic movement that has run its course and it’s now re-looping its emptiness. From physicist and cognitive scientist Jan Koenderink, that for science and art to be relevant to human beings they must focus serious attention on human perception. From philosopher David Kelley, that idealism and striving for the best are profoundly important to humanity and that art is the most powerful way to embody ideals.

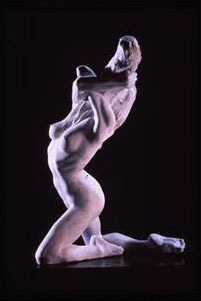

It was also great to experience the sheer depth of passion that Martine Vaugel has for her art and I hope that people came away from my presentation with excitement about the innovative work that contemporary painters and sculptors are creating.

TFR: It's been a couple of years since you announced your bold strategy to take on the art world. Have you found any need to modify your strategy at all? For instance, has the 'Highbrow Hammer' approach proved fruitful?

MN: Recently, I have had discussions with a few arts editors and postmodern gallery directors; a couple of them have tried to “Highbrow Hammer” me! I enjoyed that immensely. Many of their arguments, I believe, sounded even shallow to themselves. For example none of them had good points as to why innovative representational painters were not acknowledged and they agreed with me that they should be.

An interesting “highbrow” development coming up this spring in London is an aesthetic debate about whether or not found objects are art. Three London newspaper critics will be for and a philosopher, a writer, and an artist against.

Teaching Art

TFR: Alexandra York suggests that Art should be considered the fourth 'R' in education, because, she says “only art educates the whole person as an integrated individual; it educates the senses, it educates the mind, it educates the emotions. It educates the soul.... To teach art is to teach life." Do you see the teaching of art in the same way?

MN: Yes I do. And learning the skills of art early in life is a prerequisite for making great art…and, I believe, for acquiring a deep appreciation for it.

Develop and protect your self-esteem, listen to and please all your voices, confirm your observations and conclusions with reality, live your ideals, and unleash your passion.

Michael Newberry

TFR: How would you characterize the students you have taught? What, briefly, were you teaching them and how receptive were they? And how has your teaching helped your own work?

MN: I had a few wonderful students. I think there are young geniuses all around us and all they need is an atmosphere of reason, passion, self-esteem, and to know that important accomplishments in life are made through tremendous effort. The sad thing is that the life of an artist is so damn difficult that many students don’t have either the fortitude or the financial and moral support that they need to flourish.

I have always encouraged my students to introspectively dive down, really deep, and use the profound visual techniques of form, space, and light to unlock their souls. Trust me, when you encourage a teenager to express their deepest being and you give them the tools to do it then they love it.

I haven’t found that teaching has helped my art. I instruct students with approaches that I am already familiar with but in my projects I am pushing the limits of my knowledge.

TFR: What inspires you? What art from fields inside and outside paintings inspires you?

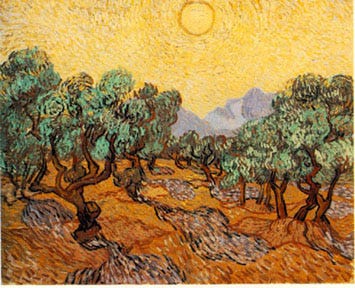

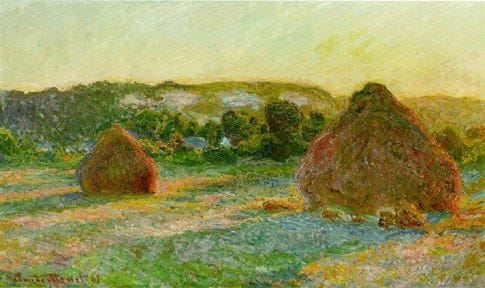

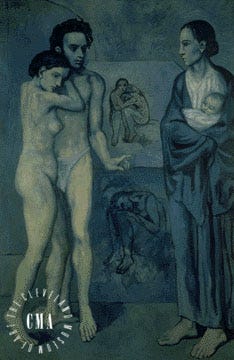

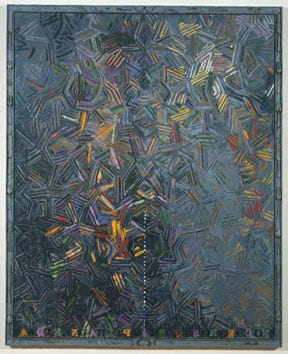

Literature, classical music, opera, sculpture, and architecture I enjoy a great deal—I don’t care much for movies, dance, or poetry. More often than not I love the entire output from individual artists. I love everything by Puccini, Bach, Beethoven, Christie, Rand, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, the French Impressionists, Jasper Johns, Picasso, Velázquez, Vaugel, Leontyne Price, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Niri, Toscanini, Argerich, Dutoit.

One magnificent painting is Las Meninas by Velázquez. It has a great composition, incredible lighting, soulful people, and phenomenal spatial relationships. For fascinating color I would look to anything by Monet or Van Gogh.

Sleeping with the Enemy?

TFR: You’ve said that you’ve read and -worse - digested Kant’s ‘Critique of Judgment.’ Would you recommend the task to others? Is there anything of any value there?

MN: What a horrible task to pass on to someone! No, I wouldn’t recommend it unless they have an interest in aesthetic theory or a general love of philosophy.

In regards to value I believe that Kant’s aesthetics are incredibly subversive. In his Concepts of Beauty he identifies artistic values of skill, positive sensory experience, form, and theme; pretty much a classic view of art. But here is the rub, he then treats the Concepts of Beauty as inferior to his Concepts of the Sublime, which are based on formlessness, instinct, mass acceptance, and violation. For a moment if you contemplate Kant’s view that formlessness is superior to form then you might see how that is a conceptual slap-in-the-face to Beethoven and Michelangelo, who are known to have the greatest form/structure in the arts. Kant’s Concepts of the Sublime maligns the values of the world’s greatest art. But one value I get from studying Kant’s aesthetics is that once you understand his position you can, with some normative application, understand the nihilism of postmodern art—and reject it. Another value is seeing how ideas, philosophical ideas, can affect all of humankind regardless of their negativity or their absurdity.

TFR: Why do you refer so often to your enemy as ‘Post-modern’? Doesn’t that term only refer to late twentieth-century crap? Surely Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists and most of the early crap were ‘Modern’? Isn't 'Post-Modernism' now passé? Aren’t the fashionable hordes now blindly following some new 'ism'?

MN: I use the word postmodernism more as a stylistic element or conceptual approach than one of general time periods. I would call Picasso a modernist and Duchamp a post-modernist. There is a significant difference between them: Picasso was a representational painter and Duchamp broke with painting and sculpture to work with arrangements of trash i.e. ready-mades.

... painting transfers reality through a soul.

Michael Newberry

TFR: Several years ago, novelist Anthony Burgess had a very public reaction to some practitioners of ‘arrangements of trash’ that makes various valid points it seems to me. “One often talks,” he wrote, “about being driven to drink. I have to record that the second programme in the ‘All Sorts to Make a World’ series sent me pubwards shivering with rage. This [documentary], ‘Art for Whose Sake?’, was as wretched a gallimaufrey of phoney aesthetics and scruffy-underdog whining as ever steamed up from the dog-end littered floor of a Soho-wine-club. We went to the Royal Academy School of Art to meet students who cultivated a deliberate lack of personal allure … Young Mr Dimbleby was their voice when he said that if photography had been invented earlier, perhaps patrons of art would not still be so obsessed with the representational. What it is now a moral duty to buy is the abstract canvas, apparently, and we do foul wrong to ask for something as reasonable as an imaginative composition of shapes that have their origin in the real world. …. I may add that these young painters (not the sculptors; the sculptors were different) spoke as graceless an English as I have heard in a long time.”

A few questions spring from that. How, for instance, has photography changed the nature of art?

MN: I don’t think anything can change the nature of art; it is integral to the human condition. There is a world of difference between painting and photography; photography transfers reality through a machine and painting transfers reality through a soul.

TFR: Do you yourself have any sneaking admiration for any abstract art or artists?

MN: Yes. I love the way Jasper Johns paints but I experience it with only a fraction of my being, the part that loves to move paint around the canvas! I like Diebenkorn very much.

The first person to come up with the concept of God was an artist trying to name what they felt.

Michael Newberry

TFR: Do you see the job of the artist then as one primarily of communication? Or of simply 'pleasing oneself'? What is it, in other words, that the artist is trying to do by putting splotches of paint on a surface? What makes him do it, and what is he after?

MN: The job of an artist is creation. Their job is to realize, to bring into existence, an idea or vision. Painting for me feels much different than say doing this interview in which I am doing my best to communicate. And, at least for me, there is nothing about “pleasing oneself.” An exhilarating part of the job is unleashing your thoughts and passions but the excruciating part is being true to visual reality i.e., light, forms, space and when it all comes together it is sublime: an act of creation. I think the first person to come up with the concept of God was an artist trying to name what they felt.

When I was a teenager someone cooked for me lemon chicken and the taste was an overwhelming sensual experience: the textures, aroma, the tingling explosion of flavor! When I make a mark of color “right” it feels like that dish. Perhaps this is one of the keys to the concept of beauty, balance is crucial, too much of one thing can destroy the delicate balance that makes for superb taste. For me a mark of color must: follow the form of the object; support the light effect; be harmonious; have an emotional quality; and it must occupy an exact position in depth. I know that sounds mind numbing, I just broke it down in detail. In real time the process of painting comes automatically as if I am massaging the color. If there is a disaster I double check those perspectives and re-work everything until I get it right.

The Creative Process

TFR: How do you generate your own ideas for a piece? Is there a common process for each work, or does each work 'come to you' in a different way? And how do you know when a piece is finished?

MN: Ideas for paintings come to me all the time through all kinds of ways. Denouement came about by thinking of what images convey my idea of the greatest moment I could experience in life. Awakening came about from a vision I had in a dream. Sometimes I stop shocked-still when I see a startling combination of light, shadows, shapes, and colors in a landscape, interior, still-life, or on a person. A person’s beauty or character often inspires me. The Slipper came about from my emotion of bursting with joy. The ideas can come from an emotion, thought, or perception.

The psychologist Devers Branden once asked me which voice was the one I paint by and I answered: “All of them.” The creative process for me is listening to every objection that voices in my head raise and then answering them by painting the solution. They often say things like: “the background wall is too far forward…the hand looks alright but I don’t feel anything…fantastic you got the life and feeling in there but that ear is all whacked … you gotta fix it…” I work until a chorus shouts: “alright man you did it!”

Pleasing my voices and getting the mark of color right confirms when I am done.

TFR: Where does that creative spark come from do you think - from where do those 'voices' appear that ignite the 'Aha!' moment that produces your idea for a work?

MN: I don’t know. But, I do my best to free my brain and life from unwanted clutter like: television sitcoms, back seat drivers, and bad food! If it doesn’t inspire me “be gone”!

TFR: There is an excitement, isn't there, in following that 'Aha!' moment by quickly sketching out that idea you're just been struck with. Do you find that any more or less pleasurable than the slow and careful - and sometimes painful - working out of all the implications of that idea? Do you enjoy either part of the process more than any other, i.e., the initiation of the spark?

MN: The initial spark is very exciting but the gratification that comes from completing a major work is profound. I mean it is one thing to have the idea and another to have worked, studied, made mistakes, and created solutions to bring the artwork into existence.

TFR: In which area do you think greater artistic maturity helps more - in producing the 'spark,' or in being able to tease out all the implications of the spark.

MN: I don’t think I feel any different about art now than 20 years ago. Maturity, for me, consists of saving time by following good leads.

TFR: Any offers of what creativity consists?

MN: Spark and action.

TFR: How do you feel when you've put your soul on canvas, and that canvas is then bought and taken out of your life? Do you ever feel torn when one of your paintings leaves you?

MN: Never! It feels great to have a work go out into the world, I love to see my works up in a collector’s home but in my studio they are facing the walls. Mostly because I don’t want to be distracted by them when I am working on something new.

Development of the Artist

TFR: In what sense does an artist's own personal life inform his work, do you think? Is it primarily your 'emotional' life from which you derive your inspiration? Or?

MN: That is difficult to answer because I invest my soul in everything I make.

Nude Self-Portrait is my most intimate work. It is about my longing for a soul mate. I encouraged the light to caress a very sensitive part of my body, next to my stomach. It is like, “yes, touch me there and I will be content.”

TFR: Which is you own favorite Newberry?

A very small and favorite work is Pastels. It’s about my sensual love of color; I feel it even when I simply look at pastels. I am in love with the medium. The feeling I get when I look at them is like wave after wave of vibrations pass around and through me—it’s like merging into the rhythm of the universe.

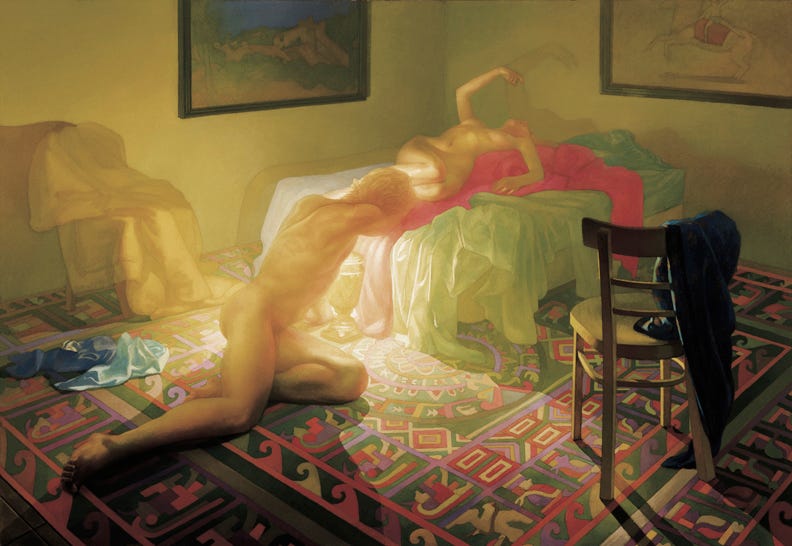

Another favorite work is Denouement for every reason I can think of: the light, the color, the intimacy and the grandeur of love, its uniqueness, the benevolence … It is my response to the question: what is the most glorious and greatest moment that a person can experience? I did not want to show someone climbing Mount Everest or solving a puzzle, or making an artwork, or building something or finishing a job—but the act of connecting on the deepest level of intimacy possible; the greatest ultimate end.

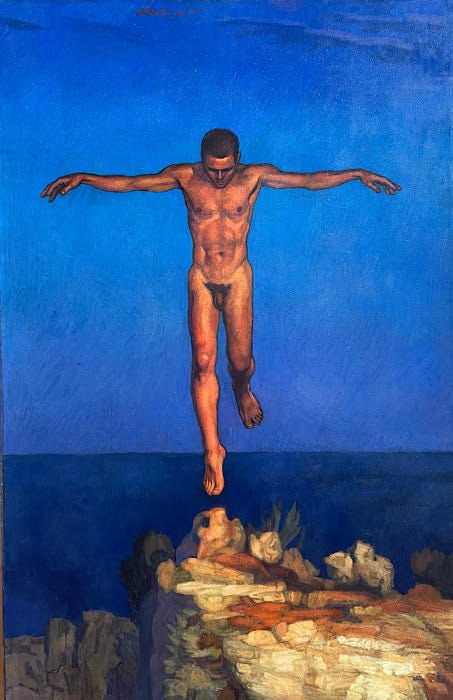

TFR: It seems to me that your own mature work seems to have worked towards a greater simplicity in composition—for example the many-splendoured richness of Denouement of 1987, as compared with the iconic delicacy of Icarus Landing. Any comment?

MN: Thanks for those adjectives! Between Denouement and Icarus Landing I spent many years on the Slipper, Synergy, and God Releasing Stars into the Universe. They are terribly complex, transparent, and very ornate in terms color and light nuance. With them I was working out the implications of light’s transparent nature … After I had finished them I wanted to change and focused on accenting concrete forms, which Icarus, Venus, and Artemis embody.

Color

TFR: Color seems very important to your own work ... Your own color palette is rich and exuberant, and it fills the canvas—you couldn't be accused of being minimalist! Do you have any comment on the metaphysical value judgments between, say, a rich 'Rembrandtesque' palette such as yours and a rather spare one like perhaps some of the achingly beautiful Japanese prints?

MN: Color for me is a very complex subject. On one level I equate color with emotional moods. On another it must serve the light and forms in the painting. I love to conceptually flip color by using an identical color to serve as shadow in one area and as a highlight in another. I am into how light imbues a hue; say a glowing transparent orange, over everything it touches and how shadow does the same with an opposite hue like cobalt. I like to alter the hues of highlights as they touchdown through space. For my art a simple red is never simple.

TFR: Pastels seems to be a selection of some of your favorite colors? Your more mature palette seems to have added a sunlit golden color to the palette that wasn't there before - is that part of a change in yourself do you think, or partly the influence of your many years in the richly toned sunlit Greek landscape?

MN: Undoubtedly you are picking up on something. When I look back on my work I can see similarities of color in chronological groupings of paintings and pastels. One of the reasons I left Los Angeles was due the color of the smog; it was invading my work! But it is easier for me to notice this in hindsight.

TFR: Yes, the light quality of your latest pieces seems to have changed (yes, I realize they are pastels). The contrast appears to have been turned down. Is this perhaps, with your move from Greece to Florida, due to your change in continents? Or just old age?

MN: I do know that there many non-visual factors that play a role in my color choices: mood, heat, wind, humidity, or a model’s character. Picasso once said that painting was a lie. Reality is interpreted through the soul of an artist. Even for a realist there is not the one way to color grass, a body, or a white wall.

TFR: Would you then expect to see a change in your color sensibility now you're resident in the rather different climate of Florida? I note you seek to keep the sun out when you're working, rather than invite it in ...

MN: Give me a few more months/years and we will see what Florida means to me in color.

About blocking the sunlight out of my studio I need a balanced and consistent neutral light to paint my studio paintings by.

Critical Judgment

TFR: How would you answer the claim that an artist is not the right one to judge his own work objectively?

MN: Bullshit. Any artist worth their salt knows what they are doing. Now, they may not be verbally articulate but if they are pushed for reasons they can come up with the goods.

Many years ago, I believe in 1975, Maria Callas gave a master class at Juilliard in New York; the sessions are documented on audio. There were many famous people and major critics in the audience; Placido Domingo attended. Previously, music critics had described the phenomenon of Callas as “instinctual”. In the sessions Callas demanded that the students understand the exact meaning of the words, that their body language had to convey the meaning of the words, they had to be true to the style of the music, they had to be note perfect, they had to convey the emotional drama of the scene and the character, they had to create nuance, they had to know how to build a climax. What came across was her towering genius, and yet she had simple explanations for everything she demanded—the synthesis was the superhuman aspect.

There are young geniuses all around us and all they need is an atmosphere of reason, passion, self-esteem, and to know that important accomplishments in life are made through tremendous effort.

Michael Newberry

TFR: A lot of artists do work for hire in order to pay the bills - portraits and the like. Do you indulge? How do you think such work affects or informs a painters own work - the work that is truly himself?

MN: My gut reaction about artists that render artistic services is not positive. Commissioned portraits and such are not part of an artist’s calling. You sell out your love. I sound very harsh on my fellow artists but the most brilliant among them have let down the future of art by reducing their art to “craft” while postmodernists who clearly follow their aims can, rightfully, claim superior artistic integrity. For a revolution in the arts to happen it is imperative that representational artists ruthlessly follow their unique visions and not allow financial or social forces to pressure them to compromise.

TFR: Do you use everything you draw or paint? What is your 'discard rate'? How much, if any, comes off your board that you'd be too embarrassed to sell?

MN: When I was a student I hoped to make one good drawing out of ten. Now it is about five to eight out of ten. Paintings are different because you can edit them until your heart’s content. If in the end a work is not “right” it hits the bin. Posted on one of my monthly Studio Updates are pictures of me shredding a painting with a razor; I had diligently worked on it for over 6 years. In this case the concept of the composition was wrong—it was doomed and I just couldn’t see it until I had exhausted every possibility.

TFR: Do you think people these days are generally more visually aware, and perhaps more sophisticated in viewing visual images than they might have been 100 years ago? And if so, how does that change the way and the 'what' that a painter produces?

MN: I don’t know. But if I look to art criticism I don’t enjoy contemporary critics half as much as reading some of the older art history books or Michelangelo’s contemporary Vasari. The contrast for me is about insight vs. vagueness. When I read Vasari it feels like I am there in the artist’s studio actually seeing them work. When I read Robert Hughes I don’t feel the truth coming through.

For a revolution in the arts to happen it is imperative that representational artists ruthlessly follow their unique visions and not allow financial or social forces to pressure them to compromise.

Michael Newberry

TFR: How would you characterize the difference, if any, between an artist/painter and a graphic designer?

MN: I can’t stand computer graphics, the games and cartoons look sickeningly artificial. Horrible. Just contrast them to Disney’s ‘Snow White.’ Related to this is an interesting phenomenon in non-animated movies, even though the affects are startling it all seems crude because they can’t integrate color, they have essentially become b/w films—it’s a strange case of going one step forward and the five backwards.

The work that Jan Koenderink and Andrea van Doorn in vision science will go a long way to giving film and computer animators the kind of knowledge they need to advance their mediums in a truthful way. My small contribution to this area is my presentation Transparency: A Key to Spatial Depth. I formulate how artists can create spatial depth while using intense color schemes. If animators understood this they would be able to integrate color more effectively with special effects.

In purely visual terms painting is king. Within the history of painting are the greatest arrangements of visual optics and the furthest insights into color and light theory. Many professional photographers are still using classic Rembrandt lighting; Rembrandt had visually formulated the greatest way, so far, to light a face, which maximized it’s structure.

TFR: Any advice for young artists, in a thousand words or less?

MN: Oh yes. Develop and protect your self-esteem, listen to and please all your voices, confirm your observations and conclusions with reality, live your ideals, and unleash your passion.

Frame of References:

Callas, Maria. Master Class at Juilliard. Callas coaches and shows opera singers how to interpret and perform great opera arias. Stunning in its simplicity and overwhelming genius when every element is integrated. About 3 hours audio: https://www.amazon.com/Maria-Callas-Juilliard-Master-Classes/dp/B000TERLLI/ref=tmm_msc_title_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1638946808&sr=1-1-catcorr

Cresswell, Peter. Renaissance man: architect, intellectual, cultural warrior, and freedom fighter. https://pc.blogspot.com/

van Doorn, Andrea and Koenderink, Jan. Today's leading vision scientists: Colors and Things, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2041669520958431

Kant, Immanuel. There is a saying "If you are going to discuss Kant, at least read him." Here is the source of his aesthetics, The Critique of Judgement, the htm online doc is easy to navigate, while the content is less so. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/48433/48433-h/48433-h.htm

Price, Leontyne. Magnificent American opera singer with one of the greatest careers of the 20th century. On January 3, 1985 I had the honor to be in the audience when the 57-year-old sang her farewell at the Metropolitan Opera house in New York. You have listen to the end and hear the ovation and see her reactions.

https://youtu.be/74HvM1lDUdw

Vasari, Giorgio. One of the original Renaissance men, painter, architect, and most notably for his art history. The Lives of the Artists is wonderfully engaging, great stories, some eyewitness accounts (he was friends with Michelangelo), perhaps it is the most important art history book ever. https://www.amazon.com/Lives-Artists-Oxford-Worlds-Classics/dp/0199537194